Introduction:

The electrical signals from the sensors must often be adjusted before they are fed to the processor. On the other side of the computer, the actuators are controlled. These are often inductive circuits that switch large currents. The hardware to adjust the sensor signals and actuator currents is called interface circuits. An interface circuit provides the translation of an analog to a digital voltage.

- Sensors send a voltage with low current. The interface circuit converts the voltage into a digital value (0 or 1).

The current strength in a sensor signal is low; - Actuators require a higher current strength.

To control the actuators, the ECU contains final stages in the form of (a combination of) transistors or FETs, also known as “drivers”. We will explore this further in the “output signals” section.

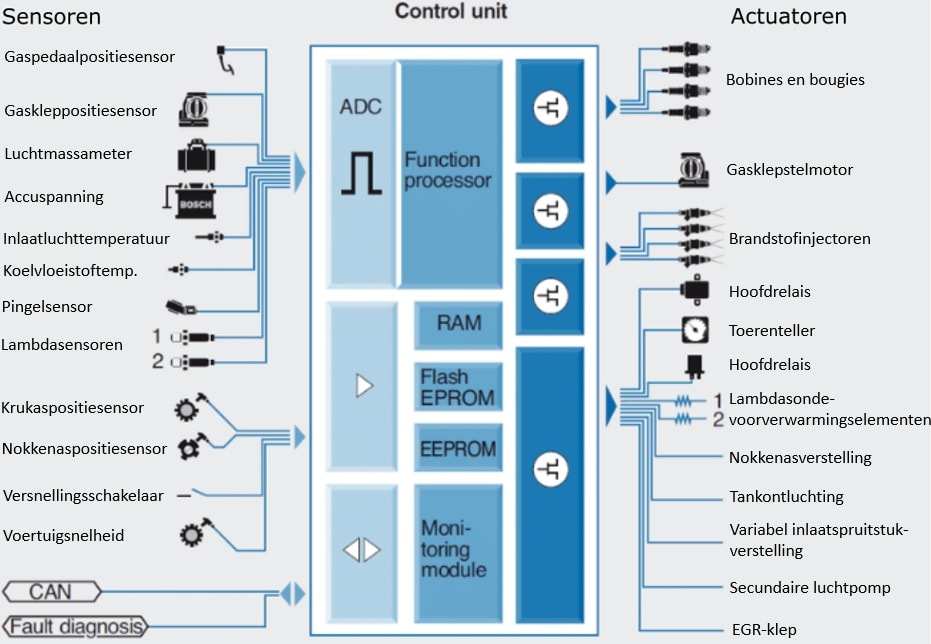

The image below shows the sensors and actuators of a (gasoline) engine management system. The top group of sensors (from the accelerator pedal position sensor to the lambda sensors) fall under the category “analog”. That means that the incoming sensor voltages must first be digitized in the ADC (analog – digital converter). The bottom group of sensors (from the crankshaft position sensor to the vehicle speed sensor) already offers their signal digitally. The on-off signals or block voltages are directly presented to the CPU.

The actuators on the right are controlled by a final stage. A final stage, also known as a driver, consists of a circuit of multiple transistors to generate a usable voltage and current from a control pulse from the computer to drive the actuator.

Transistor Transistor Logic (TTL):

The processor operates with voltages of 5 volts. Input and output voltages are thus limited to a range of 0 to 5 volts (TTL level, short for Transistor Transistor Logic). For signals deviating from this voltage level, an adjustment takes place in an interface circuit.

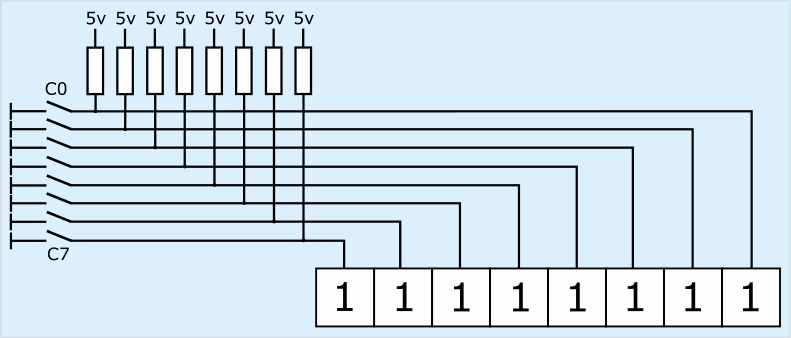

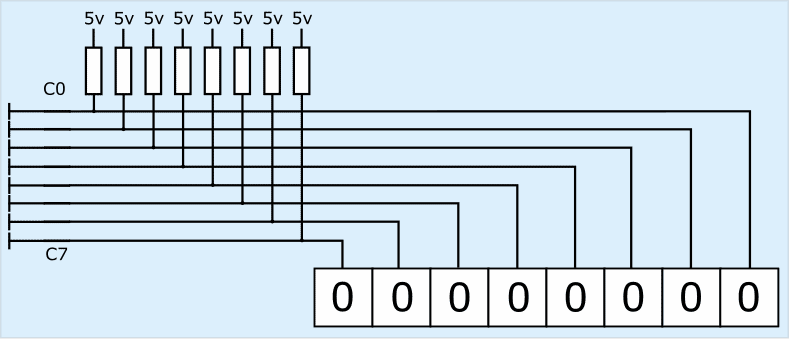

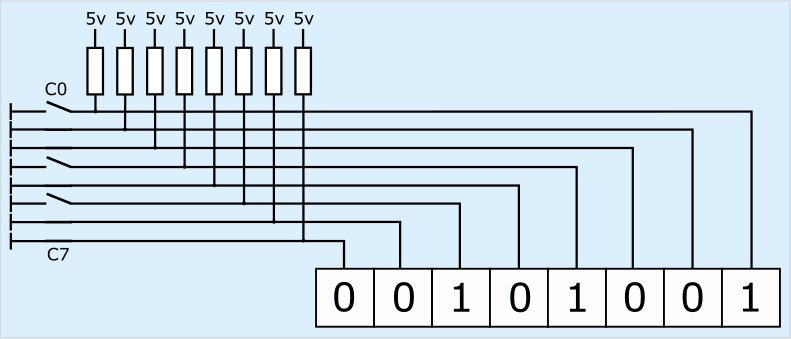

The images below show how a 1 or a 0 is formed from a switch position. Using a pull-up resistor, the 5-volt supply ensures a logical 1 at the processor input when the switch is open. The voltage across the pull-up resistor is not then switched to ground.

When the switches close, a voltage drop occurs across the pull-up resistor. The 0-volt voltage at the processor input is interpreted as logical 0.

A combination of open and closed switches provides a sequence of ones and zeros. The image shows the 8-bit message to the processor: 00101001.

With an 8-bit processor, the eight bits are read simultaneously per cycle. During the next cycle, which occurs during the next “tick” of the clock (see the system bus on the page about the operation of the ECU), a series of eight new bits follows.

Conversion of Analog Sensor Voltages to Digital Message:

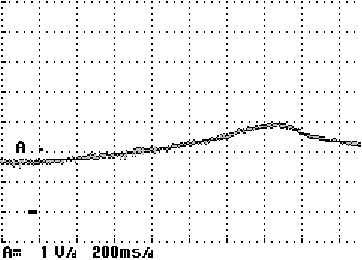

Digital input signals are directly processed by the processor. Analog signals are first converted into a digital signal in the A/D converter. As an example, we take the analog voltage curve of a turbo pressure sensor:

- at idle, the voltage is approximately 1.8 volts;

- when accelerating, the voltage rises to almost 3 volts.

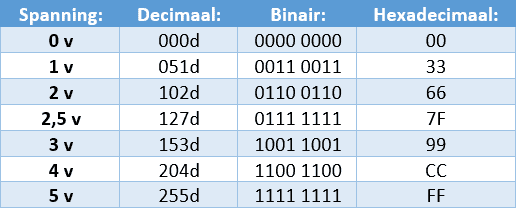

The voltage change cannot be processed directly in the processor. First, the measured voltage must be converted into a decimal value (0 to 255).

With a range of 0 to 5 volts and a decimal value of 0 to 255 (256 possibilities in total), a simple calculation shows that when we distribute 5 volts over 256 possibilities, increments of 19.5 mV (0.0195 volt) can be made.

The example above showed the voltage curve over time for a turbo pressure sensor. The voltage curves of a temperature sensor and an accelerator pedal position sensor follow similarly, just within a different timeframe: after all, the coolant takes longer to warm up than the turbo to spool up.

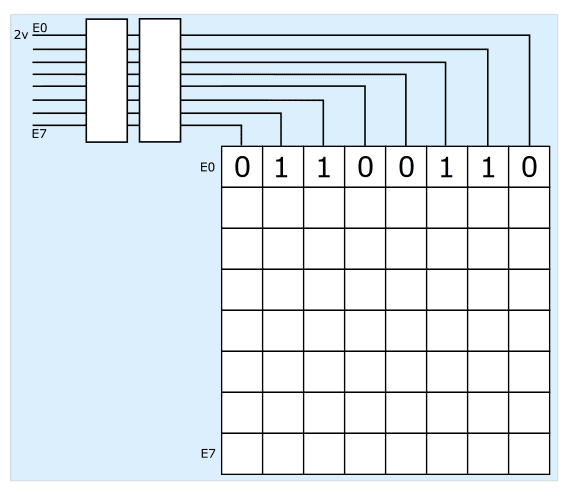

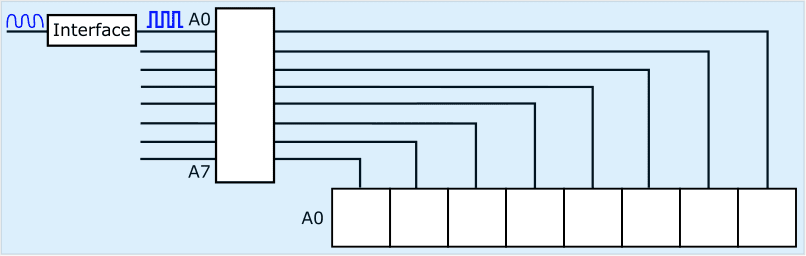

Earlier in this section, an image was shown where a category of analog signals is depicted. These include the temperature sensor and the accelerator pedal position sensor. The analog voltage is converted into an 8-bit unit of information in the A/D converter. Many processors with multiple input pins have only one A/D converter. Multiple analog signals are combined into one signal via multiplexing.

In this example, we see an A/D converter with eight inputs. On pin 0 is a voltage of 2 volts. Pins E1 through E7 can be simultaneously supplied with voltages. These are converted one by one to a digital message via multiplexing.

The voltage of 2 volts is converted to a binary value. Using the following formula, we can convert the analog voltage to a decimal value and then convert it to a binary value:

2v / 5v * 255d = 102d

Here, we divide the input voltage (2v) by the maximum voltage (5v) and multiply this by the maximum decimal value (255).

Through calculation or performing a handy trick, we can convert the decimal number of 255d into the binary value of 01100110.

See the page: binary, decimal, hexadecimal.

The following table displays the decimal, binary, and hexadecimal value that corresponds with different voltages.

When reading live data, it may happen that the decimal, binary, or hexadecimal value of the sensor signal is shown.

- A voltage signal of <0.5 volt (025d) is seen as a short with ground;

- If the signal exceeds 4.5 volts (220d), the computer interprets this as a short with the positive.

Conversion of Pulse Generator Signals to a Digital Message:

Pulse generator signals, including the inductive crankshaft position sensor, are essentially on-off signals created when the teeth of the pulse wheel move past the sensor. The sensor’s alternating current must first be converted into a block voltage before the signal is offered to the processor.

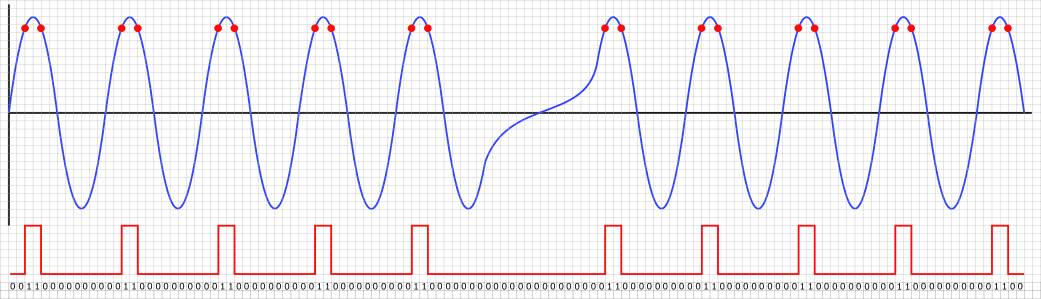

In the image, we see sinusoidal alternating voltages on the left side of the interface. In the interface electronics, this alternating voltage is converted into a block voltage. This block voltage is then read by the timer/counter block: when the pulse is high, the counter starts counting, and stops when the pulse is high again. The number of counts is a measure of the period time or frequency of the signal.

In the image below, we see a signal from the inductive crankshaft sensor with red points on the upper flanks. The red points are set to a voltage to make the block voltage rise (logical 1) or fall (logical 0). Below this image, the explanation continues.

However, the sensor voltage is never completely pure. A slight fluctuation will always be visible in the voltage curve. In such cases, the interface electronics may wrongly interpret this as a logical 0, while it should actually be a 1.

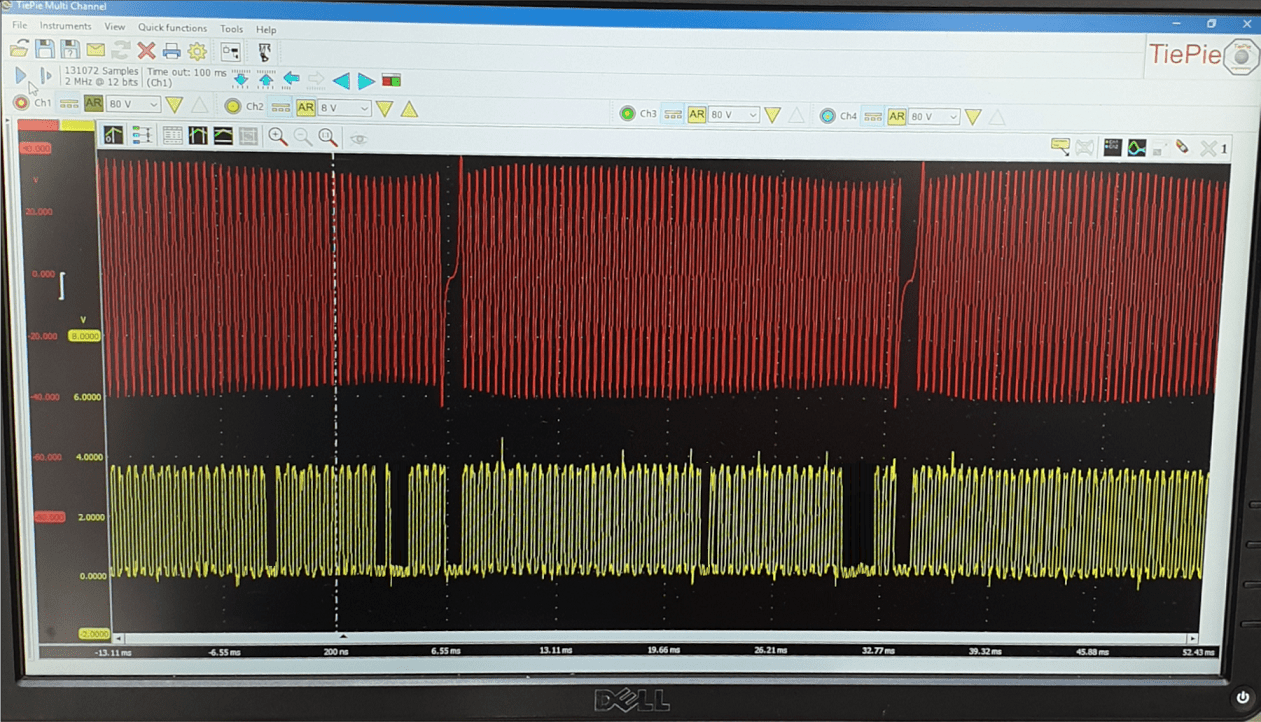

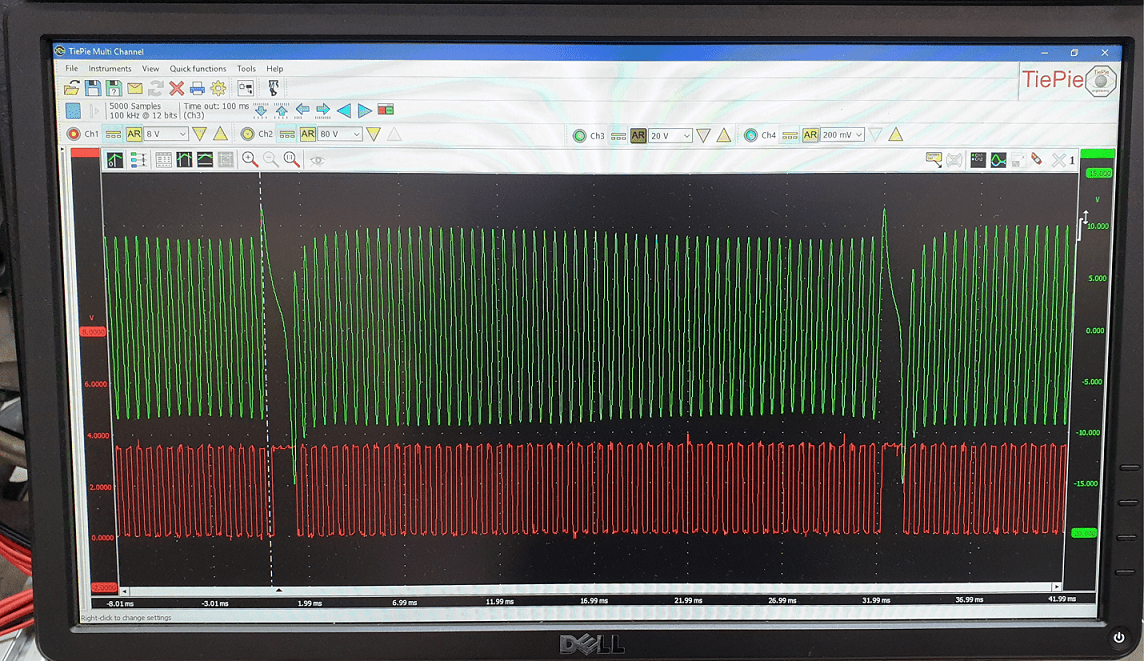

The scope image below was recorded during the execution of the BMW-Megasquirt project. The scope image shows the digitization (yellow) of the inductive crankshaft signal (red). It is clearly visible that there are missing pulses in the yellow block signal while no missing tooth in the crankshaft signal passes by at that time.

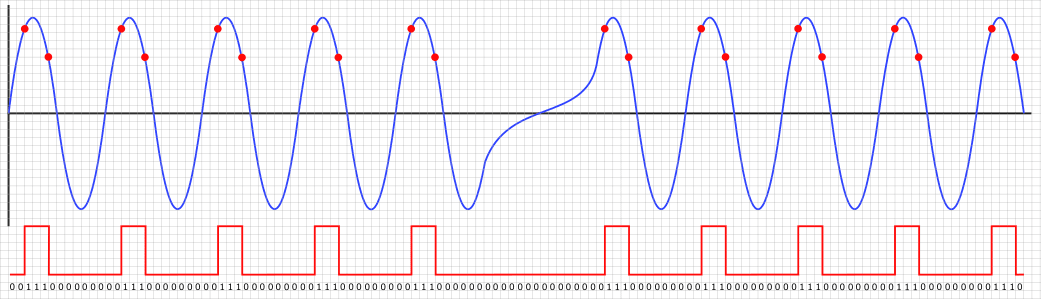

To ensure that small fluctuations in the voltage curve do not lead to incorrect interpretation by the ECU, a so-called hysteresis is incorporated. The hysteresis is the difference in voltage between the rising and falling edges of the voltage curve. In the image below, we see that the red points of the rising edges are at a higher voltage than the red points on the falling edges. This ensures that small fluctuations in the signal have no effect on the digital conversion.

In the first section where we started discussing the conversion of the pulse signal to the digital signal, it was already mentioned that the frequency of the signal is determined based on the time between two rising edges of the block signal. In these examples, it is clearly deduced that the hysteresis does influence the width of the block signal but does not affect the time between the rising edges, and therefore has no effect on the frequency of the signal.

With a well-set hysteresis, the sinusoidal signal is well converted to a usable block voltage, with only the multiple logical ones at the places where the missing tooth passes by.

Note, during the setup of the MegaSquirt ECU, settings have been changed, including triggering on the rising and falling line. Therefore, when passing the missing tooth in the first example, the voltage is 0 volts and in the scope image below, the voltage is 5 volts.

Output Signals:�a0

The output signals consist of digital on/off pulses with a voltage range between 0 and 5 volts (TTL level) with very low current strength. However, actuators require control with higher voltage levels and current strengths.

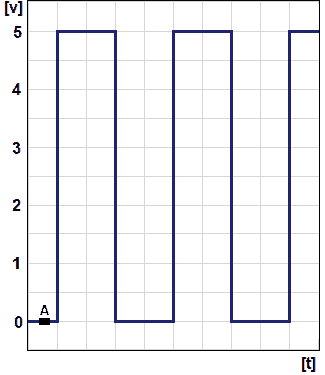

The on/off signals can be pulse-width modulated (PWM), where the pulse width can vary at a constant frequency.

The next image shows a block voltage at TTL level as a function of time. The duty cycle of this PWM signal is 50%.

Drivers are required to drive actuators. With the digital output signal, a driver can achieve the required current strength. In the next section, we discuss the drivers.

In every ECU and in some actuators like DIS coils, we find drivers. A driver is also called a final stage or power transistor. The driver enables the conversion of output signals at TTL level: 0 to 5 volts, with low current strength of 1 mA from the ECU to voltages up to 14 volts and currents up to approximately 10 A.

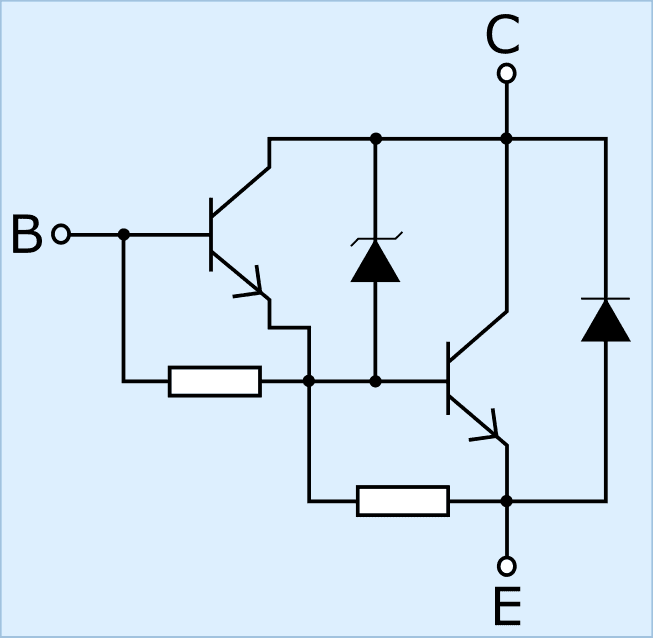

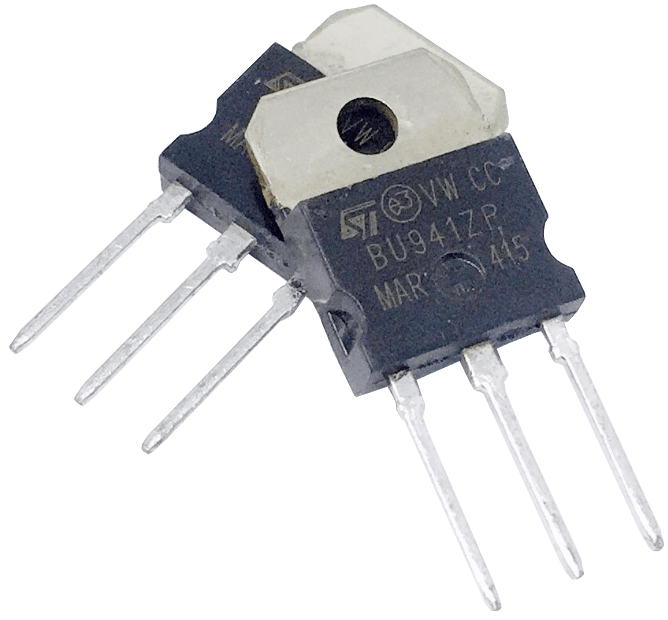

A driver can contain multiple interconnected transistors. Such a transistor is called a “Darlington transistor“. The following images show the following circuits:

- Diagram of a Darlington circuit with two transistors for the coil control (source: datasheet BU941ZR).

- Two transistors each with a Darlington configuration (BU941ZR)

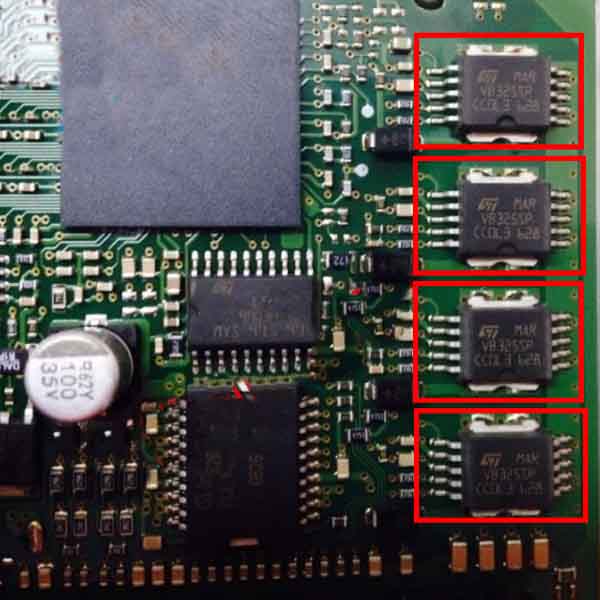

- Driver ICs with Darlington configurations and additional electronics for, among other things, temperature protection and feedback to the microprocessor.

The page: control methods actuators delves deeper into the control of passive, active, and intelligent actuators using a (power) transistor or FET.