Introduction:

Sensors measure physical quantities and convert them into electrical voltages. These voltages are processed in the microcontroller (ECU) and read as a “signal.” The signal can be assessed based on the voltage level or the frequency with which a signal changes.

Passive sensors:

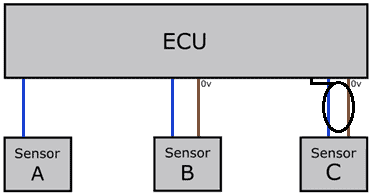

A passive sensor detects and measures a physical quantity and converts it into another physical quantity. An example of this is converting temperature into a resistance value. A passive sensor does not generate its own voltage but reacts to a reference voltage from the ECU. A passive sensor does not require a supply voltage to function.

Passive sensors typically have two or three connections:

- reference or signal wire (blue);

- ground wire (brown);

- shielded wire (black).

Sometimes a passive sensor contains only one wire: in that case, the sensor housing acts as ground. A third wire may serve as shielding. The sheath is grounded through the ECU. The shielded wire is primarily used for signals sensitive to interference, such as those from the crankshaft position sensor and the knock sensor.

An example of a passive sensor is an NTC temperature sensor. The reference voltage of 5 volts is used as a voltage divider between the resistor in the ECU and in the sensor, not as a supply voltage for the sensor. The voltage level between the resistors (depending on the NTC resistance value) is read by the ECU and translated into a temperature. The circuit with the resistors is explained in the section: “Power supply and signal processing” further down this page.

Active sensors:

Active sensors contain an electrical circuit within the housing to convert a physical quantity into a voltage value. The electrical circuit often requires a stabilized power supply to operate.�a0

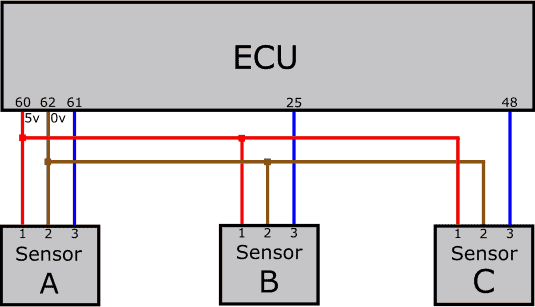

This type of sensor generally has three connections:

- positive (usually 5.0 volts);

- ground;

- signal.

The stabilized 5-volt power is provided by the control unit and used by the sensor to form an analog signal (between 0 and 5 volts). Often, the positive and ground wires from the ECU are connected to multiple sensors. This can be recognized by the nodes where more than two wires are connected.

The analog signal is converted into a digital signal in the ECU.�

In the section “power supply and signal processing,” we will delve deeper into this.

Intelligent sensors:

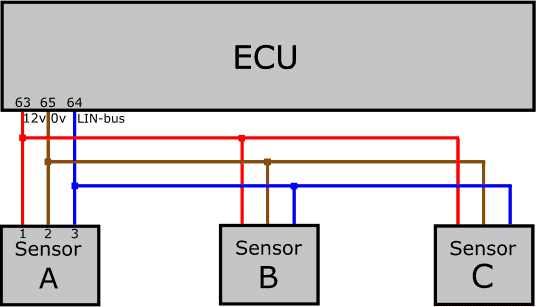

Intelligent sensors are usually equipped with three connections. Similar to active sensors, there are a power wire (12 volts from the ECU or directly via a fuse) and a ground wire (via the ECU or an external ground point). An intelligent sensor sends a digital (LIN-bus) message to the ECU and other sensors. This operates on a master-slave principle.�

Internally in the sensor, an A/D converter converts an analog to a digital signal.

- Analog: 0 – 5 volts;

- Digital: 0 or 1.

In the LIN-bus signal, in the recessive state (12 volts), it is a 1, and in the dominant state (0 volts), it is a 0.

Applications in automotive technology:

In automotive technology, we can categorize the different types of sensors as follows:

Passive sensors:

- Knock sensor;

- Crankshaft position sensor;

- Temperature sensor (NTC / PTC);

- Lambda sensor (jump sensor / zirconium);

- Inductive height sensor;

- Switch (on / off)

Active sensors:

- Crankshaft / camshaft position sensor (Hall);

- Air mass meter;

- Wide-band lambda sensor;

- Pressure sensor (boost / turbo pressure sensor);

- ABS sensor (Hall / MRE);

- Acceleration / deceleration sensor (YAW);

- Radar / LIDAR sensor;

- Ultrasonic sensor (PDC / alarm);

- Position sensor (throttle / EGR / heater flap).

Intelligent sensors:

- Rain / light sensor;

- Cameras;

- Pressure sensor;

- Steering angle sensor;

- Battery sensor

Measuring sensors:

When a sensor is not functioning correctly, the driver will notice in most cases because a warning light will illuminate or something will no longer work properly. If a sensor in the engine compartment causes a malfunction, it could lead to power loss and a lit MIL (malfunction indicator lamp).

When reading an ECU, a fault code may be displayed if the ECU recognizes the malfunction. However, not all cases immediately identify the cause via the fault code. The fact that the sensor concerned is not working may be because it is defective, but there is also a possibility of an issue with the wiring and/or connector connections.

It may also be the case that the sensor provides an incorrect value, not recognized by the ECU. In that instance, no fault code is stored, and the mechanic must seek out measurement values that are out of range using live data (see the OBD page).

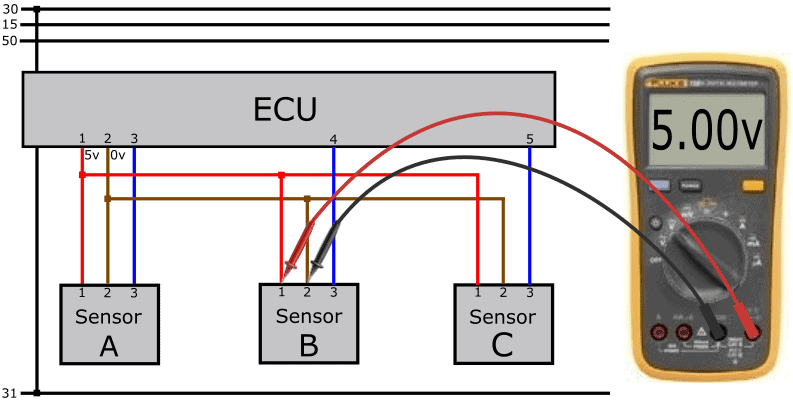

The following image shows a measurement of an active sensor. A digital multimeter is used to check the sensor’s power supply (the voltage differential on the positive and negative terminals). The meter indicates 5 volts, so this is correct.

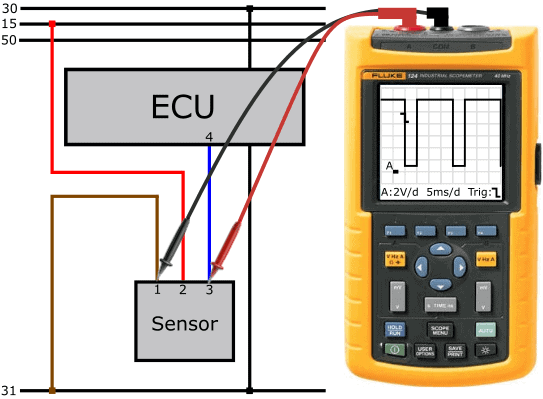

Signal voltages can be measured with a voltmeter or an oscilloscope. The type of signal determines which meter is suitable:

- voltmeter: analog signals that are almost constant;

- oscilloscope: analog and digital signals (duty cycle / PWM).

With one or more measurements, we can demonstrate that the sensor is not functioning correctly (the signal produced is implausible, or the sensor gives no signal), or there is a problem with the wiring.

For passive sensors, a resistance measurement can usually be performed to check for any internal defect in the sensor.

Possible problems in sensor wiring can be:

- disconnection in the positive, ground, or signal wire;

- short circuit between wires or to the chassis;

- transitional resistance in one or more wires;

- poor connector connections.

On the page: Troubleshooting sensor wiring, we delve into seven potential malfunctions that can occur in sensor wiring.

Signal transmission from sensor to ECU:

There are different methods for transmitting signals from the sensor to the ECU. In automotive technology, we may encounter the following signal types:

- Amplitude Modulation (AM); the voltage level conveys information;

- Frequency Modulation (FM); the signal frequency conveys information;

- Pulse Width Modulation (PWM); the time variation in the block voltage (duty cycle) conveys information.

In the following three examples, scope signals of the different signal types are shown.

Amplitude Modulation:

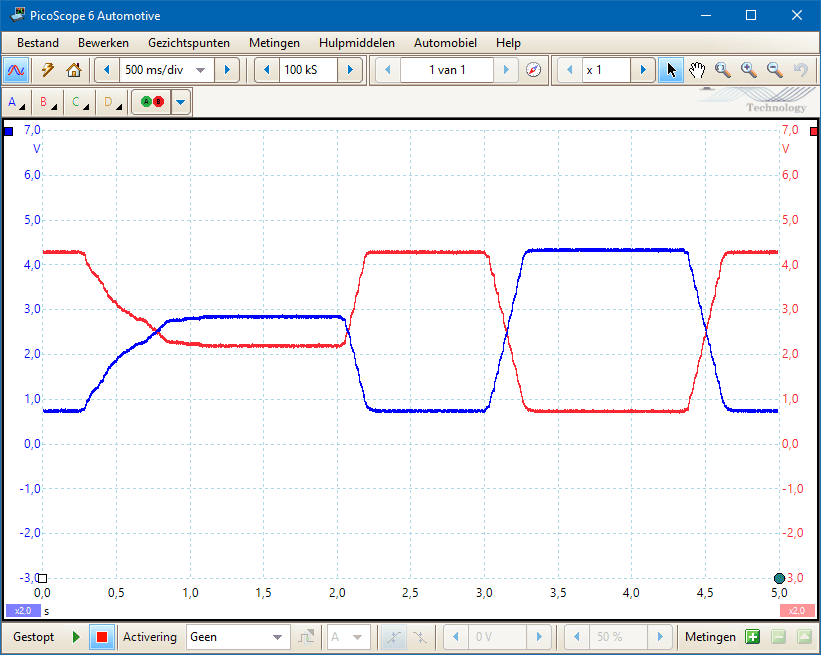

For an AM signal, the voltage level transmits the information. The image shows two voltages from the throttle position sensors. To ensure reliability, the voltage curve must be mirrored relative to each other.�

Voltages at rest:

- Blue: 700 mV;

- Red: 4.3 volts.

Approximately 0.25 seconds after starting the measurement, the accelerator pedal is slowly pressed, and the throttle opens 75%.

At 2.0 sec, the accelerator pedal is released, and at 3.0 sec, full throttle is applied.

Voltages at full throttle:

- Blue: 4.3 volts;

- Red: 700 mV.

Frequency Modulation:

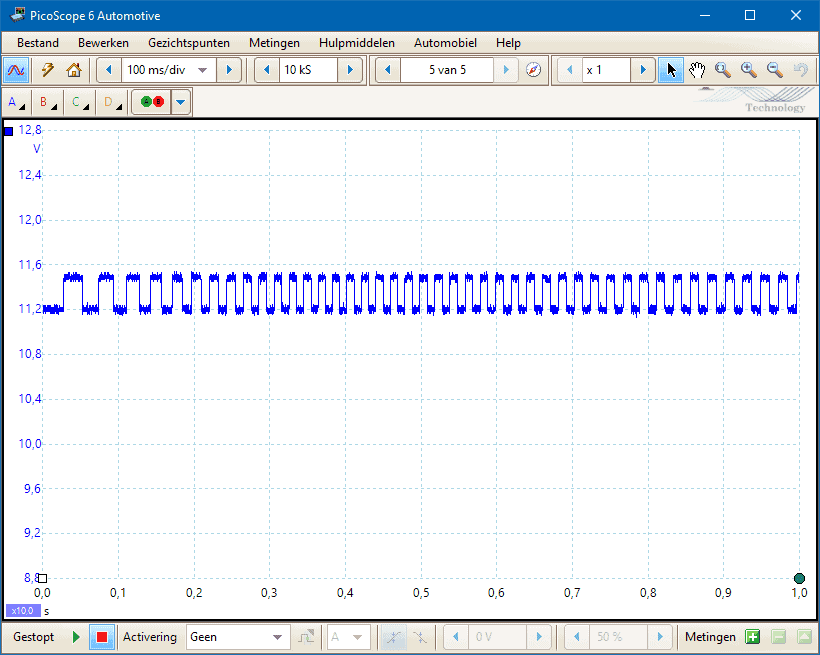

For sensors that send an FM signal, the amplitude (height) of the signal does not change. The width of the block voltage transmits the information. The following image shows the signal of an ABS sensor (Hall). During the measurement, the wheel was spun. A higher wheel speed results in a higher signal frequency.

The voltage difference arises from the change in the magnetic field in the magnet ring, which is incorporated in the wheel bearing. The height difference (low: magnetic field, high: no magnetic field) is only 300 mV. If the scope is set incorrectly (voltage range from 0 to 20 volts), the block signal is barely visible. For this reason, the scale is adjusted so the block signal becomes visible, making the signal appear less pure.

Pulse Width Modulation:

For a PWM signal, the ratio between high and low voltage changes, but the period remains the same. Do not confuse this with a block voltage in an FM signal: the frequency and therefore the period change.�

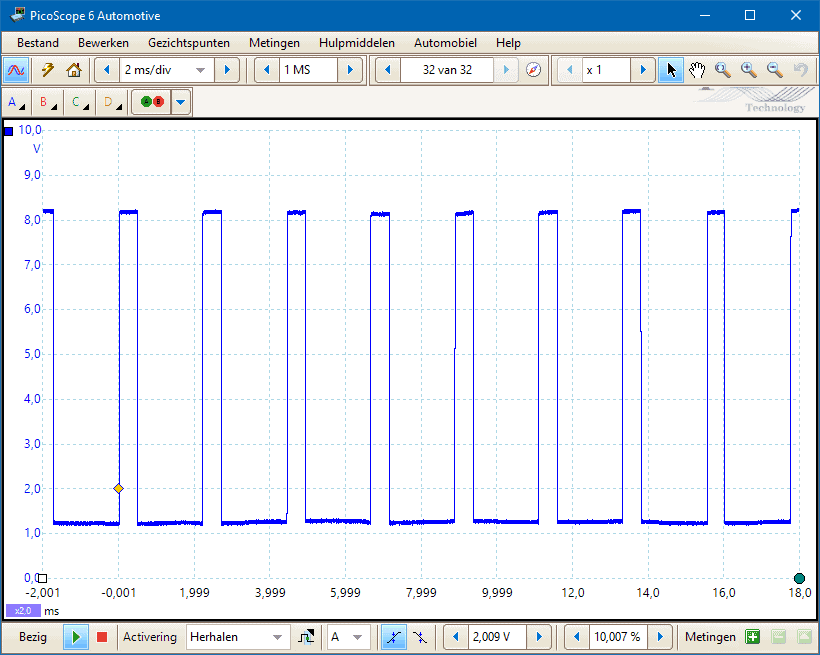

The following two images show PWM signals from a high-pressure sensor in an air conditioning line. This sensor measures the medium pressure in the air conditioning system.

Situation during the measurement:

- Contact on (sensor receives a supply voltage);

- Air conditioning off;

- Read medium pressure with diagnostic equipment: 5 bar.

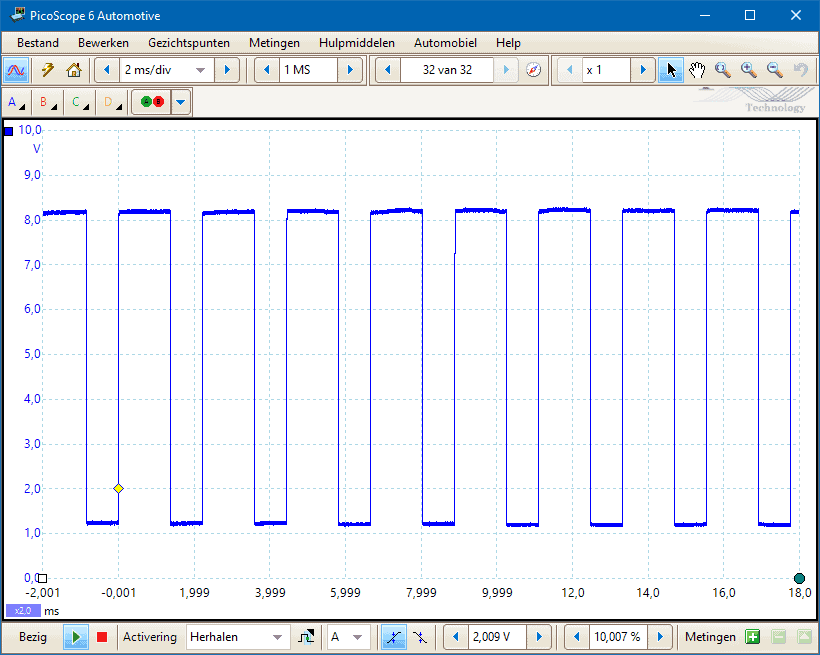

In the next scope image, we see that the period remains the same, but the duty cycle has changed.

Situation during the measurement:

- Air conditioning on;

- High pressure has risen to 20 bar;

- Duty cycle is now 70%

Analog sensors can transmit a signal using AM. A voltage signal like this is prone to voltage loss. Transitional resistance in a wire or connector results in voltage loss, and hence a lower signal voltage. The ECU receives the lower voltage and uses the signal for processing. This can cause malfunctions because multiple sensor values no longer correspond, resulting in:

- Two ambient air temperature sensors measuring different temperatures simultaneously. Although a small margin of error is acceptable and the ECU may adopt the average value, a too-large difference can lead to a fault code. The ECU detects the discrepancy between the two temperature sensors.

- Incorrect injection duration because the MAP sensor’s signal is too low, leading the ECU to misinterpret engine load. In such a case, fuel injection is too long or too short, and the fuel trims correct the mixture based on the lambda sensor signal.

In a PWM signal and/or SENT signal, voltage loss does not play a role. The ratio between rising and falling edges is a gauge for the signal. The voltage level does not matter. For example, the duty cycle may be 40% with a voltage fluctuating between 0 and 12 volts, but the ratio remains 40% when the supply voltage drops to 9 volts.

SENT (Single Edge Nibble Transmission)

The sensors signals mentioned above have been a standard in passenger and commercial vehicles for years. In newer models, we increasingly see sensors using the SENT protocol. These sensors appear similar in reality and schematic as regular active sensors.

For passive and active sensors, information transfer occurs via two wires. For instance, with a MAP sensor: one between the NTC sensor and the ECU, and the other between the pressure sensor and the ECU. The sensor electronics of a SENT sensor can combine the information transfer of multiple sensors, reducing the number of signal wires. Moreover, the signal transfer remains unaffected by voltage loss over the signal wire, just like with a PWM signal.

A sensor using the SENT protocol has, like an active sensor that transmits an analog or digital signal, three wires:

- Power supply (often 5 volts)

- Signal

- Ground.

Sensors with the SENT protocol transmit a signal as “output.” There is no bidirectional communication, as seen with LIN-bus communication between sensors.

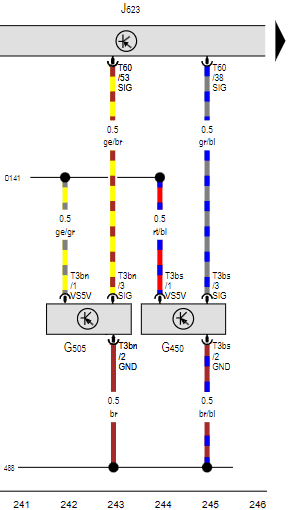

In the diagram on the right, we see the differential pressure sensor (G505) of a VW Passat (model year 2022). The diagram shows the usual indications of the power supply (5v), ground (GND), and signal (SIG). This pressure sensor converts the pressure into a digital SENT signal and sends it to pin 53 on connector T60 in the engine ECU.

The differential pressure sensor in the above example sends only one signal via the SENT protocol over the signal wire. Multiple sensors can be connected to one signal wire using SENT. This can be applied to a MAP sensor (air pressure and air temperature) and an oil level and quality sensor.

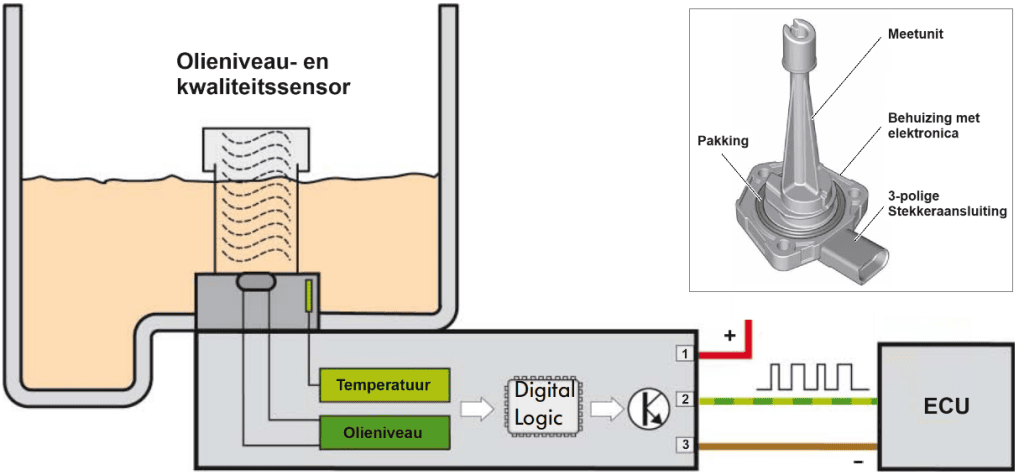

In the following image, we see an oil level and quality sensor mounted in the oil pan of a combustion engine. Both measurement elements are located in the engine oil.

The sensor is supplied with 12 volts, receives its ground via the ECU, and transmits the signal using SENT to the ECU.

The microcontroller in the housing digitizes the message (see: “digital logic” in the image) incorporating both the oil temperature and level into the SENT signal.

Below, we explore the structure of a SENT signal.

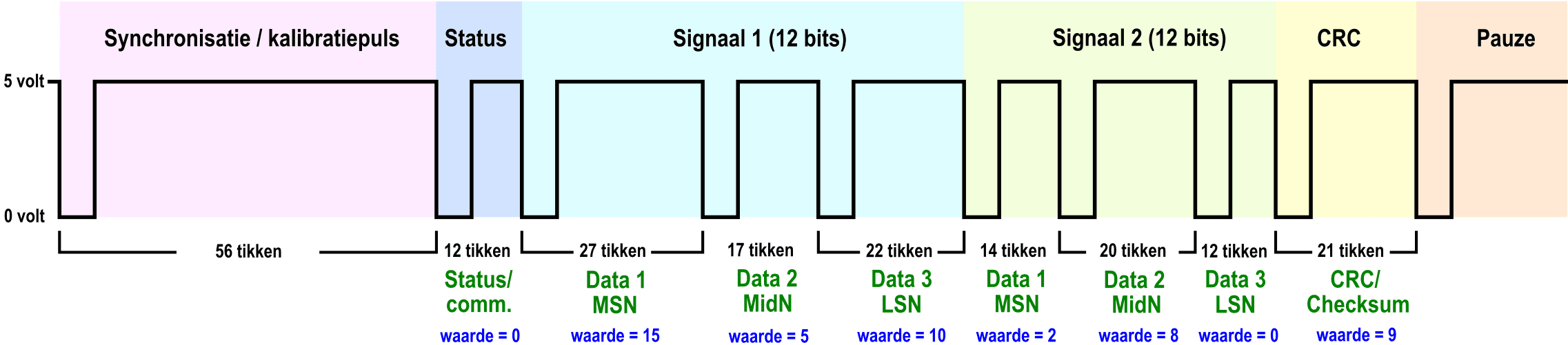

A SENT signal is composed of a series of nibbles (groups of four bits) that transmit information by sending voltages between 0 and 5 volts. Here’s a short description of how a SENT signal is structured. Below is the image showing the message’s structure.

- Synchronization / Calibration Pulse: This often marks the start of the message. This pulse allows the receiver to identify the beginning of the message and synchronize the clock timing;

- Status: This section indicates the status of the transmitted information, for example, whether the data is correct or if there are issues;

- Message Start Nibble (MSN): This is the first nibble and indicates the start of a SENT message. It contains information about the message’s source and data transfer timing.

- Message Identifier Nibble (MidN): This nibble follows the MSN and contains information about the message type, message status, and any error detection or correction information.

- Data Nibbles: Following the MidN are one or more data blocks, each consisting of four data nibbles. These blocks carry the actual data being transmitted. They contain information such as sensor data, status information, or other useful data.

- Cyclic Redundancy Check (CRC): In some cases, a CRC nibble may be added at the end of the message to facilitate error detection. The CRC nibble is used to check if the received data was correctly received.

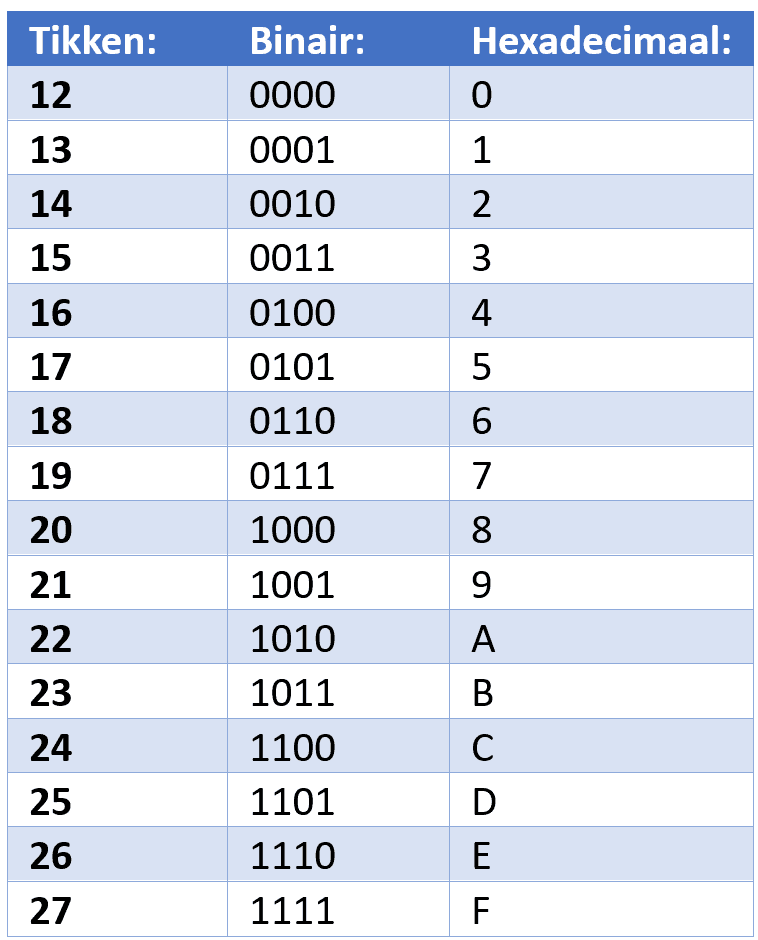

Each nibble in a SENT signal can have values from 0 to 15, depending on how many ticks it is at 5 volts. The image below shows the structure of the SENT protocol.

‘Nibble groups’ are sent, numerically from 0000 to 1111 in binary format. Each nibble represents a value from 0 to a maximum of 15, and they are displayed in binary as such: 0000b to 1111b and in hexadecimal from 0 to F. These digitized nibbles contain the sensor values and are sent to the ECU.

To transmit this nibble information, ‘ticks’ or computer ticks are used. The clock tick indicates how quickly the data is transmitted. The clock tick is usually 3 microseconds (3µs) to a maximum of 90µs.

In the first case, this means a new nibble group is sent every 3 microseconds.

The message begins with a synchronization/calibration pulse of 56 ticks. For each of the two signals: signal 1 and signal 2, three nibbles are sent, which results in a sequence of 2 * 12 bits of information. After these signals, the CRC

(Cyclic Redundancy Check) is sent for validation, allowing the receiver to verify if the received data is correct.

Finally, a pause pulse is added to clearly indicate the end of the message to the receiver.

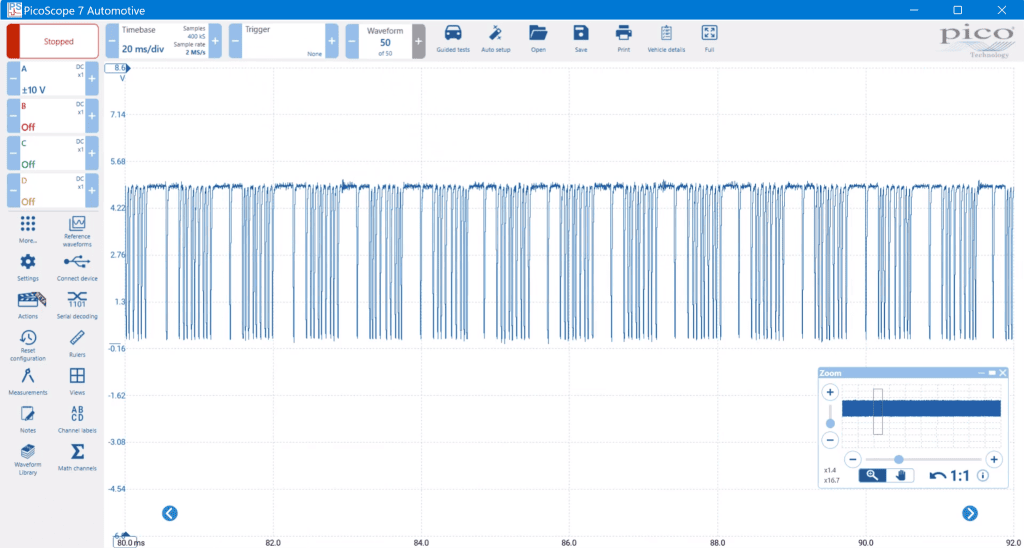

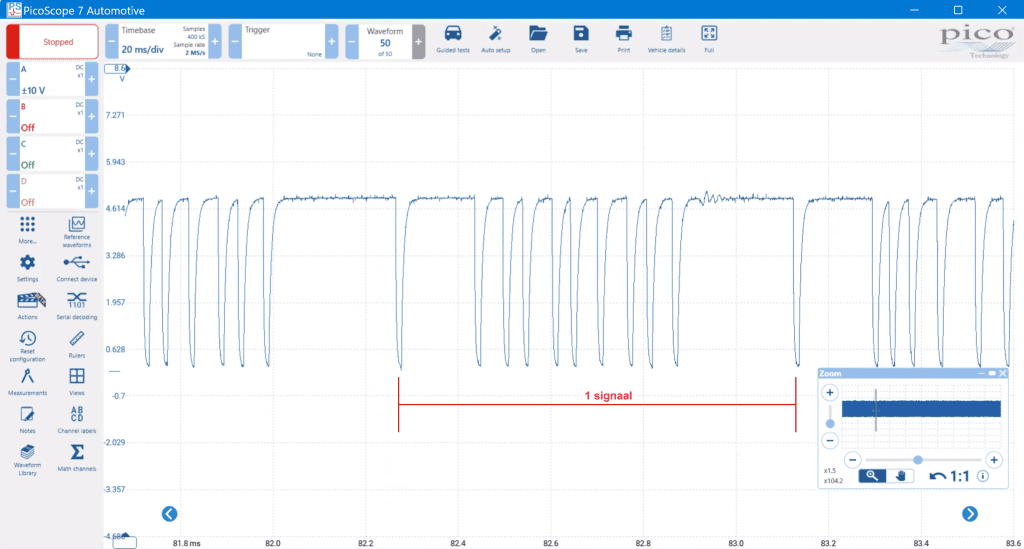

The following scope images (recorded with the PicoScope Automotive) show measurements of multiple messages (left) and a zoomed-in view of a single message (right). The zoomed-in message indicates in red where the signal starts and ends. When conditions change: pressure and/or temperature rise, then one or more nibbles will show a change in the number of ticks. This change in ticks will be seen in the lower scope image as one or multiple voltages fluctuating between 0 and 5 volts. The pulses can become wider or narrower. The actual information can be decoded with the Picoscope software.

With an electrical diagnosis, we can decode the message using the Picoscope software to study it, but in most cases, we focus on checking a clean message sequence without noise and whether the power supply (5 volts) and ground of the sensor are in order.

Power supply and signal processing:

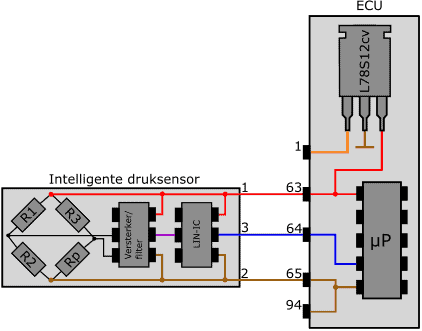

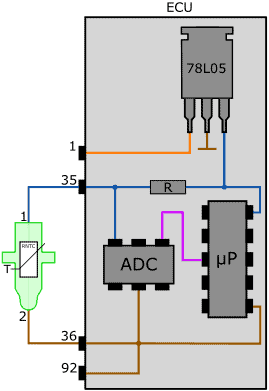

In the initial sections, there was discussion about the presence or absence of a supply voltage. In this section, we discuss the main components in the ECU responsible for the power supply and signal processing of the respective sensor. The pin numbers of the in-depth schematics correspond with those in previous sections: pin 35 and 36 of the ECU are connected to pin 1 and 2 of the passive sensor, etc.

In the first image, we see an NTC temperature sensor. The reference voltage (Uref) from pin 35 of the ECU is obtained from the voltage stabilizer 78L05. The voltage stabilizer provides a voltage of 5 volts with a board voltage from 6 to 16 volts.

The resistor R (fixed resistance value) and RNTC (temperature-dependent resistor) form a series circuit and also a voltage divider. The Analog-Digital Converter (ADC) measures the voltage between the two resistors (analog), translates it into a digital signal, and sends it to the microprocessor (�).

Using a multimeter, one can measure the voltage at pin 35 of the ECU or pin 1 of the sensor.

On the temperature sensor page, alongside some measurements with a good signal transfer, the measurement techniques for a wiring malfunction are shown.

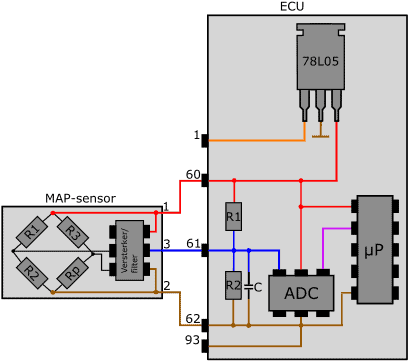

The second image shows the circuit of an active MAP sensor.

The stabilized 5-volt power reaches the “Wheatstone Bridge” which consists of several fixed (R1, R2, R3) and one variable resistor (Rp).

The resistance value of Rp depends on the pressure in the intake manifold. Here too, we have a voltage divider. The change in resistance causes a change in voltage, resulting in an imbalance of the bridge. The voltage difference that arises in the Wheatstone Bridge is converted in the amplifier/filter into a voltage with a value between 0.5 and 4.5 volts. In the analog-digital converter (ADC), the analog signal is digitized. The ADC sends the digital signal to the microprocessor.

The resolution of the ADC is usually 10 bits, divided over 1024 possible values. With a voltage of 5 volts, each step is approximately 5 mV.

In the ECU’s internal circuit, there are one or more resistors incorporated in the power and signal circuits for passive and active sensors. The resistor in the NTC circuit is also known as the “bias resistor” and is used for the voltage divider. Resistors R1 and R2 in the ECU circuit of the MAP sensor aim to allow a small current to flow from the positive to the ground.

Without these resistors, a so-called “floating measurement” would occur in the event of a broken signal wire or disconnected sensor connector. The circuit with resistors ensures that in those cases, the voltage on the ADC input is pulled up to approximately 5 volts (minus the voltage over resistor R1). The ADC converts the analog voltage into the digital value 255 (decimal), thus FF (hexadecimal), and sends this to the microprocessor.

A very small current flows through resistor R1 (low Ohmic). There is a slight voltage drop of between 10 and 100 mV. It may happen that the applied voltage is a few tenths higher than 5 volts; between the ground connection of the 78L05 voltage stabilizer and the ECU ground (brown wire in the above diagram), a low-ohmic resistor is connected. The voltage drop over this resistor may be, for example, 0.1 volts. The voltage stabilizer sees its ground connection as an actual 0 volts, so it raises the output voltage (the red wire) by 0.1 volts. The voltage sent to the sensor’s positive is thus not 5.0 but 5.1 volts.

The intelligent sensor receives a voltage of 12 volts from the ECU. In the intelligent sensor, just like in the active sensor, a Wheatstone bridge and an amplifier / filter are included. The analog voltage from the amplifier is sent to the LIN interface (LIN-IC).

The LIN interface generates a digital LIN-bus signal. The signal varies between 12 volts (recessive) and about 0 volts (dominant). With this LIN-bus signal, the sensor communicates with the other slaves (mostly sensors and actuators) and the master (the control unit).

On the wire between pin 3 of the sensor and pin 64 of the ECU, there are branches to the master and other slaves.

For more information, see the page LIN-bus.