Introduction:

Every internal combustion engine contains valves. There is always at least one intake and one exhaust valve. These valves are driven by the Timing via one or more Camshafts, allowing fresh air to enter the combustion chamber, trapping the air during compression, and then allowing it to leave again. The flow of intake and exhaust gases should proceed with as little resistance as possible.

The materials are shaped as optimally as possible for this purpose.

The valves are installed in the cylinder head. The intake valve is often larger than the exhaust valve to allow as much mixture as possible to enter the cylinder. The exhaust valve can be smaller because burnt exhaust gases will leave the cylinder during the exhaust stroke when the piston pushes the gases out.

As an example, let’s consider the four-stroke process of a gasoline engine. During the intake stroke, the intake valve opens and in an indirect injection gasoline engine, an air-fuel mixture is drawn in, whereas in a direct injection gasoline engine, only fresh air is drawn in. The air is drawn in because the piston moves downward. The space created is filled by the incoming air. When the piston moves back up, the intake valve closes. The mixture of fuel and air cannot escape and is compressed. This is known as the compression stroke. Therefore, it’s important for the valves to close properly. The mixture is ignited by the spark plug giving a spark. This pushes the piston down with significant force. This is called the power stroke.

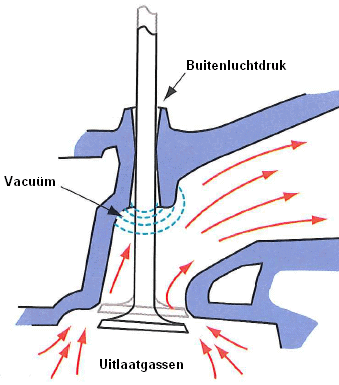

During the exhaust stroke, the exhaust valve opens and the piston moves up. The burnt gases now exit the cylinder and go to the exhaust. When the piston reaches the top, the exhaust valve closes and the intake valve opens. The piston moves down once again, leading to the intake stroke. In fact, the intake valve opens slightly earlier, so both the intake and exhaust valves are open simultaneously for a short time. This is known as “valve overlap.” The speed of the burnt gases exiting the cylinder past the exhaust valve creates a vacuum, enhancing the intake of air. This allows more air to enter the cylinder than just opening the intake valve with the piston moving downward would. This improves the volumetric efficiency.

For a more detailed explanation of the four-stroke process, see the page “Operation of a gasoline engine“.

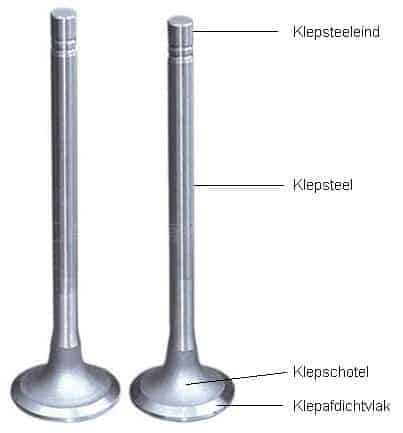

Material:

Valves are heavily loaded, especially exhaust valves because they become extremely hot and have limited cooling. Intake valves are partially cooled by the cold incoming air that enters the cylinder. Along the exhaust valves, hot exhaust gases flow with a temperature of up to 900 degrees Celsius. Therefore, exhaust valves are made from different material than intake valves. Intake valves are often made from chrome-nickel steel. Exhaust valves are often made from chrome-silicon steel. To minimize wear under high-temperature conditions, the outer edges of the valve head (the sealing surface) and the valve stems are coated with a layer of hard metal alloy (Stellite). The valves dissipate most of the heat via the valve head and valve stem. Sodium-filled valves offer even better heat dissipation.

Sodium-filled valves:

Exhaust valves are hollow inside. The hollow space is filled with approximately 60% sodium. Sodium is a metal that becomes liquid at high temperatures (from around 100 degrees Celsius). In a running engine, the valve frequently moves up and down. The sodium in the valve is constantly sloshed back and forth, transporting the heat. The sodium absorbs heat from the valve head and transfers it to the valve stem. Sodium-filled valves can achieve a temperature drop of 80 to 100 degrees compared to non-sodium-filled valves.

Intake valves do not require this, as they are already cooled by the incoming air.

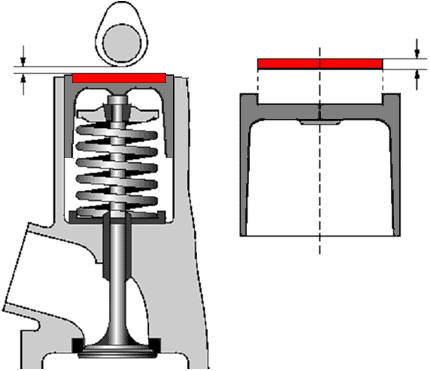

In the image, the gray surface represents the material, and the red area represents the hollow space filled with sodium.

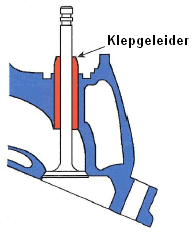

Valve guides:

The valves move up and down in the cylinder head. There must be a good seal between the valve and the cylinder head to prevent oil from flowing from the cylinder head along the valve stem into an intake or exhaust port. There is always a small oil film present between the valve and the guide to provide lubrication. In the image, the valve guide is shown in orange.

If blue smoke comes out of the exhaust, it can be due to defective valve guides. The guides may have become larger (see the image below), allowing the valve to have play in the cylinder head. In this situation, oil can enter the intake or exhaust port along the valve. At the top of the valve guide is the outside air pressure, or sometimes even overpressure due to higher crankcase pressure. At the bottom of the valve guide, gases flow to the exhaust manifold, creating a vacuum effect. This is enhanced by the oil being sucked down along the valve stem. When the oil reaches the exhaust manifold, it does not burn, but instead heats up, causing it to partially evaporate. The result may be blue smoke coming from the exhaust.

Valve guides can often be replaced separately. For this, the cylinder head must be disassembled, and the valve removed from the cylinder head. The valve guides can then be replaced. Not all cylinder heads allow separate replacement of the valve guides. Reconditioning companies often have a solution for this. Inquire about the possibilities of replacing valve guides at a well-regarded reconditioning company.

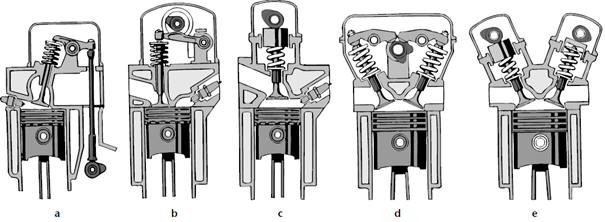

Different types of valve operation:

Valves can be operated in various ways. The image below shows five different designs. These different designs and adjustment methods are discussed later on this page.

- A: Indirect valve operation with rocker arms.

- B: Direct valve operation with roller rockers.

- C: Direct valve operation with hydraulic lifters.

- D: Direct valve operation with rocker arms and multiple valves per cylinder.

- E: Direct valve operation with hydraulic lifters and multiple valves per cylinder.

For engines without hydraulic lifters (A, B, and D), it is necessary to periodically check valve clearance. More about this can be found in the section “Adjusting valve clearance” on this page. For engines with hydraulic lifters, adjusting the valve clearance is not necessary and also not possible; the hydraulic lifters are filled with oil, which eliminates the excess clearance.

Indirect valve operation:

In the past, engines were built with an underhead camshaft. Nowadays, passenger car engines are only built with overhead camshafts. The underhead camshaft design is becoming obsolete. The drawback of this design is that these engines permit lower revs because there is a lot of mass between the camshaft and valve. At high engine speeds, excessive clearance will occur, and the valve will not open and close at the correct times.

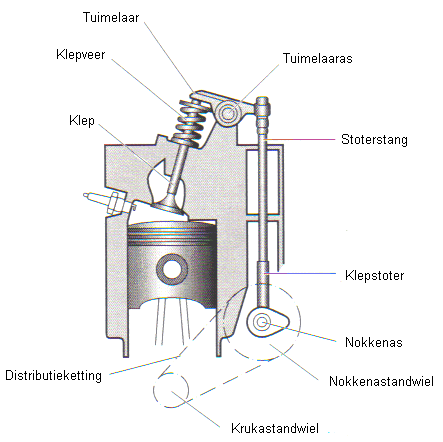

The crankshaft drives the underhead camshaft through a small timing chain or belt (see image below). The camshaft pushes the tappet and pushrod straight up. The right side of the rocker arm is pushed up. The rocker arm ‘rocks’ around the rocker shaft, causing the left side to be pushed down, thereby opening the valve against the valve spring’s force. As the camshaft rotates further, the valve spring closes the valve and returns the rocker arm to the starting position.

Direct valve operation:

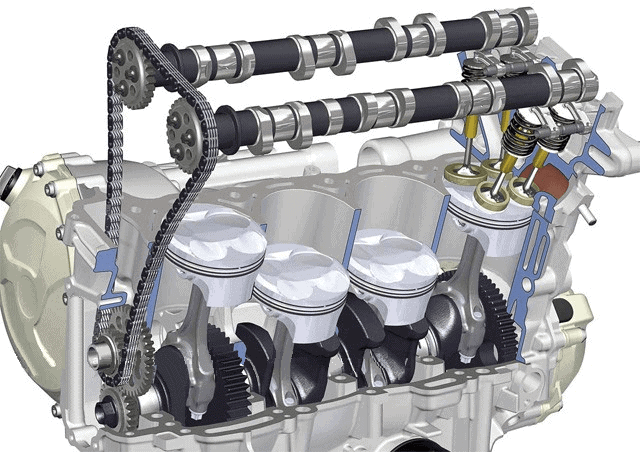

Nowadays, the overhead camshaft is used exclusively in passenger car engines. The camshaft is then placed in the cylinder head. The advantage of engines with an overhead camshaft is that they can run at higher revs than engines with an underhead camshaft.

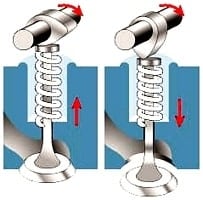

In the left image above, you can see the valve is closed because the valve spring presses the valve shut and the camshaft rotates to the right. In the right image, the camshaft has rotated, causing the cam to press the valve down. The spring is now compressed, pushing the valve down. When the camshaft rotates further, the valve spring will push the valve back up. The valve spring exerts a counter-pressure of about 20 kg.

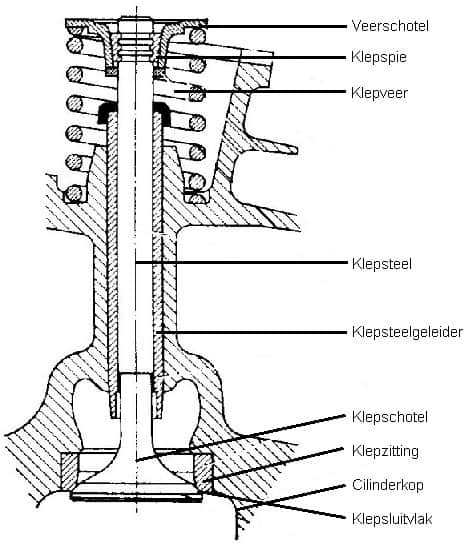

The image shows a schematic representation of a valve with a valve spring. It clearly shows where the valve sits on the valve seat of the valve seat ring. At the top are the spring retainer (the part where the cam lobe contacts the valve to push it down) with the collets and valve spring beneath it. The collets act as a valve mounting. To remove the valve from the cylinder head, the collets must be removed. During disassembly, the spring retainer must be pushed down against the valve spring force (special tools are available for this). The valve will then be free to move. By using a magnet to remove the two collets between the spring retainer and the valve stem, the valve can be removed from the cylinder head from below.

When assembling, ensure that the correct valve is fitted back in its place. These must not be swapped. When a new valve is installed, it must be lapped with special grinding paste. After lapping, the valve will seal well. The new valve can then be slipped through the valve stem guide, and the collets can be placed back in position. After this, the valve spring can be relaxed again.

Adjusting valve clearance:

There must always be a certain amount of clearance between the camshaft and the rocker arm or the top of the valve. This clearance allows the material to expand. The clearance should not be too large; otherwise, the valve will open less far and for a shorter duration. If the clearance is too large, it takes longer for the camshaft to press the valve open and it will close sooner. The clearance must also not be too small; the valve will open earlier and close later. The valve then remains open too long each time. The time the valve remains closed is, therefore, shorter; there is a risk that the valve will not be able to dissipate its heat to the valve seat of the cylinder head and could overheat, causing the valve to burn.

Nowadays, almost all passenger cars are equipped with hydraulic lifters. However, there are still manufacturers developing engines where the valve clearance needs to be adjusted. It was not common to use hydraulic lifters in cars from the 90s. Therefore, there are still many vehicles on the road where the valve clearance must be checked and adjusted periodically. The factory data usually indicates when this should be done (usually at each major service). There are two different constructions for adjusting the valve clearance; using shims or adjusting eccentric bolts. These are described below.

When adjusting the valves, you cannot start at random. It is important to pay attention to the point when the valves are “rocking.” Rocking means the camshaft has just closed the exhaust valves and is about to open the intake valves. When cylinder 1 is rocking, it means it is at the beginning of the intake stroke. The piston of cylinder 1 is then at the top. Cylinders 1 and 4 always occupy the same position (just as 2 and 3 are at the same height, see image below). Because the firing order is 1-3-4-2 (think about the power diagram), it means cylinder 4 is at the beginning of the power stroke. After cylinder 4, it’s cylinder 2’s turn, followed by cylinder 3.

In the image below, the piston of cylinder 1 is in the BDC position. The cams point downward; the intake valves have just closed, and the exhaust valves are about to open. At that moment, the valves of cylinder 4 can be adjusted; the cams are pointing upwards there.

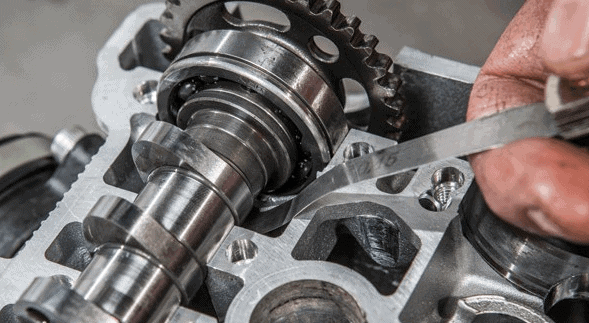

The valve clearance is measured with a “feeler gauge.” The feeler gauge consists of various gauges with metal strips, each 0.05mm thicker than the other. By sliding a number of strips between the camshaft and the valve, the amount of clearance present can be checked. The particular strip should not be pushed through too easily; the valve clearance is then greater than the strip’s value. If the strip doesn’t fit or goes in very tightly, the strip is too thick. Some resistance should be felt when moving the strip through.

Adjusting valve clearance using shims:

The thickness of the shim, also known as a “shim,” determines the valve clearance in this case. In the image below, the shim is indicated in red. By replacing the shim with a thicker piece, the valve clearance is reduced. This is because there is less space between the camshaft and the shim. Below the image, it is explained how to adjust the valve clearance. To adjust the valves, the lobe of the respective valve must be pointed upwards, as shown in the image below. If the lobe is rotated, incorrect measurements will be made. When adjusting the valves of a four-cylinder engine, the following steps should be followed:

- Cylinder 1 rocking = Adjust valves of cylinder 4.

- Cylinder 2 rocking = Adjust valves of cylinder 3.

- Cylinder 3 rocking = Adjust valves of cylinder 2.

- Cylinder 4 rocking = Adjust valves of cylinder 1.

The factory value for the above valve clearance may be, for example, 0.35mm. Therefore, there should be a 0.35mm gap between the shim and the camshaft when the lobe is directed upwards. The space between the two parts can be measured with the feeler gauge. If the strip of 0.35mm goes through very easily without feeling any resistance, it means the gap between the valve and camshaft is greater than 0.35mm. In that case, the valve clearance is too large. If a strip of 0.45mm on the feeler gauge almost doesn’t fit because it requires a lot of force to wedge it through, this strip is too thick. The actual clearance is then between 0.35 and 0.45mm. For certainty, you can try to slide a strip of 0.40mm in between. If there is resistance, but it can still be moved back and forth (there should be a touch of resistance), then you know for sure; the valve clearance is 0.40mm instead of the prescribed 0.35mm.

Since the valve clearance is too large, a thicker shim should be installed. The sizes are often marked on the shims. Read the value of the shim that is too thin. For instance, it might be 2.75mm.

The valve clearance is too large; the shim needs to be 0.05mm thicker than the one installed, namely the 2.75mm one. Installing a 2.80mm shim in this case will make the valve clearance correct. Fit the 2.80mm shim, rotate the crankshaft twice so the correct valves are rocking again, and recheck the valve clearance.

There is often special tool for easily replacing the shims. An example of this can be seen in the image.

Adjusting valve clearance using adjustable eccentrics:

An often-used system is the adjustable eccentric. The adjustment screw can only be turned when the locknut is undone by a quarter turn. When the adjustment screw is then turned, the space between the valve stem and the rocker arm will become directly larger or smaller. By tightening the locknut afterward, the adjustment screw is secured again.

Of course, the valves of the correct cylinder must first be rocking! By using the feeler gauge with the correct thickness (therefore the same value as the factory value) between the valve stem and the rocker arm, you can determine whether the valve clearance is too large, too small, or correct. By turning the adjustment screw and constantly moving the feeler gauge through, the correct position of the adjustment screw can be found where the valve clearance is correct. Tighten the locknut and then recheck if the clearance remains the same. There is a high possibility that the adjustment screw turns slightly when tightening the locknut unless using a special tool prescribed by the manufacturer.

Multi-valve technology:

Every four-stroke engine has at least 1 intake valve and 1 exhaust valve. More powerful and efficient engines often have 2 intake valves and 2 exhaust valves. Some types have 2 intake valves and 1 exhaust valve or 3 intake valves and 1 exhaust valve.

There are two major advantages to using multiple valves, namely:

- The valves will have a smaller diameter, resulting in a lower mass (less weight) per valve. This has the greatest advantage that the valves do not float at high engine speeds. Floating valves mean that when the engine is running at high speed (e.g., 5000rpm), the valves open and close so quickly that the valve springs do not have time to close the valve. Therefore, the valve does not fully seat on the valve seat. This can result in the piston hitting the valve or the valve overheating as it cannot transfer heat to the seat. With multiple valves, the valves are lighter, and the springs have enough time to close the valve.

- With the lower mass per valve, the valves can be closed faster. This makes it possible to apply variable valve timing, where the camshaft angle is adjusted at a certain engine speed or load.

Variable valve timing and lift:

Modern engines often use variable valve timing. Some engine manufacturers also apply variable valve lift (e.g., BMW). These chapters are separately described on the pages: