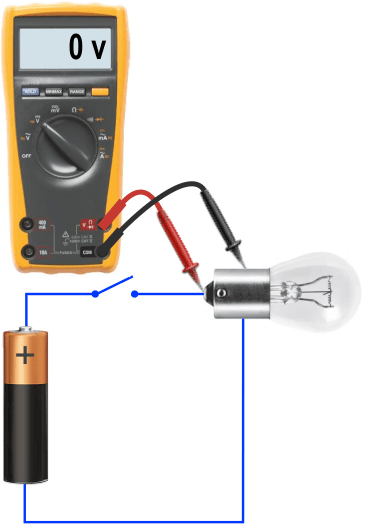

Measuring voltage:

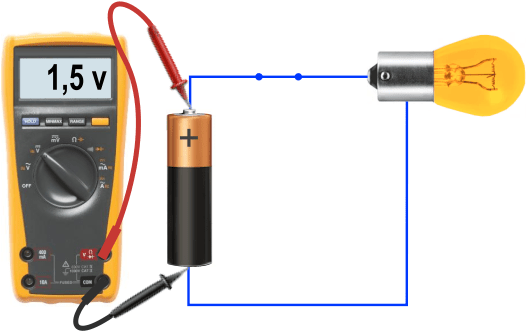

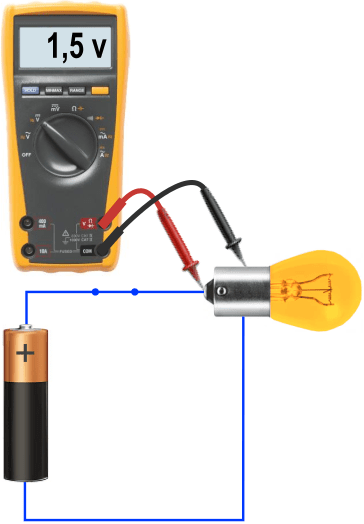

With a multimeter, we can measure the voltage (volt) across electrical components such as the battery, wiring, switch, and lamp. We then also call it a “voltmeter.” We place the multimeter in parallel over the circuit and set it as follows:

- Turn the dial to the V for volt (voltage);

- In this case, we choose direct current (DC);

- Red test lead into the V connection;

- Black test lead into the COM connection.

The red test lead is the plus wire, and the black one is the minus wire. Test probes are attached to the ends of the test leads. We hold the red test probe against the positive terminal of the battery and the black against the negative. In this way, we measure the voltage difference in the battery. We read this voltage from the display and it amounts to 1.5 volts.

The battery voltage of 1.5 volts is conducted by the plus wire to the positive terminal of the lamp when the switch is closed. With the multimeter, we measure the voltage difference across the lamp: the lower point is the plus, and the housing is the ground. We hold the test probes against the plus and ground to measure the voltage difference across the lamp.

When the switch is opened, the circuit is broken. No more current flows through the circuit, causing the lamp to go out. The multimeter indicates 0 volts with this difference measurement. The switch is on the plus side of the lamp, making the lamp voltage-free. In a paragraph further on, we will go deeper into plus and ground-switched lamps and the associated differential measurements.

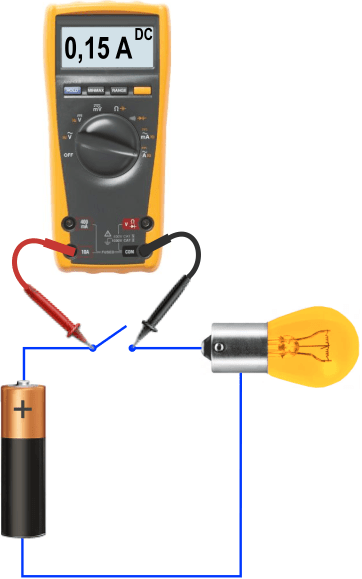

Measuring current:

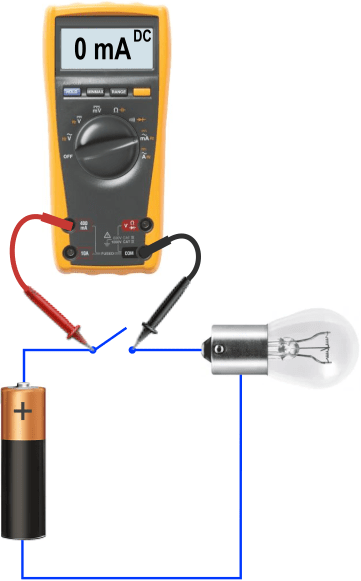

With the multimeter, we can determine how much current flows through a circuit. It’s important to connect the multimeter in series. The current flows through the multimeter. We then call it an “ammeter.” We set it up as follows:

- Turn the dial to the A for ampere;

- With this type of multimeter, press the yellow button each time the A position is chosen to switch from AC to DC;

- Red test lead into the 10A connection;

- Black test lead into the COM connection.

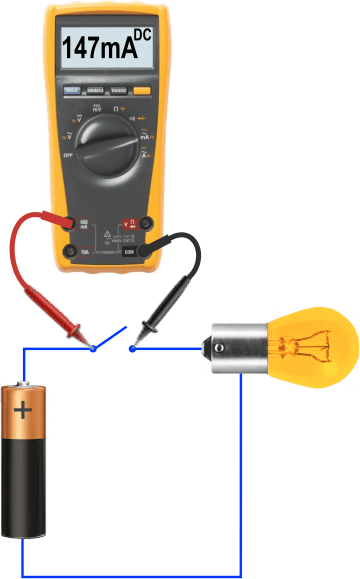

To set the multimeter in series, the current circuit must be interrupted somewhere. We can do this by removing the fuse or opening the switch. You connect the test probes where the circuit is interrupted. The two images below show the current measurement with the switch open. Measurements are taken in amps and milliamps. More explanation follows below the images.

As we can see in the images, the current can be measured in two modes.

- The first measurement is in the ampere mode. In this mode, current strengths up to a maximum of 10 amperes can be measured;

- The second measurement is in the milliampere mode. In this mode, current strengths up to a maximum of 400 milliamperes can be measured. This is equal to 0.4 A.

If you’re not sure how much current flows through a circuit, it’s wise to measure in the 10A mode first. If the current is less than 0.4 A, you can decide to insert the test probe into the mA connection and turn the dial to mA. Remember to press the yellow button to switch from AC to DC. The measured value matches, but is more accurate in the mA mode

- 0.15 A is equal to 150 mA;

- 147 mA is thus 0.147 A (this mode is more accurate).

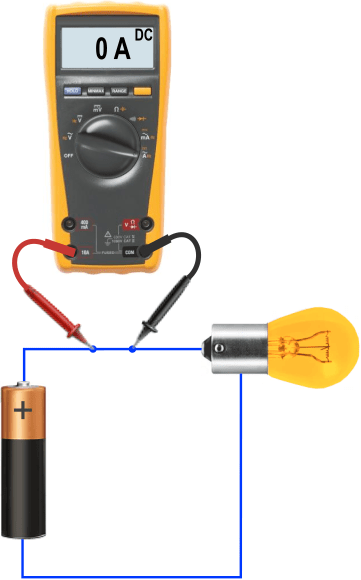

Errors are sometimes made when measuring current. The most common mistakes are shown in the next two images.

At the moment we perform a measurement where the consumer functions well, in this case, the burning lamp, but the multimeter indicates 0 A, then the meter is still in AC, or the circuit is not interrupted. The current follows the path of least resistance, which is through the closed switch. In fact, the multimeter is now parallel over the circuit. Nothing will go wrong because of this. As soon as the switch is opened, the correct value appears on the display.

If the current has risen above the value of the fuse, the fuse will break to protect the electronics in the multimeter. In the mA mode, this is 400 mA. One becomes aware of this when the meter is connected correctly, but the consumer remains off and the meter indicates 0 mA or 0 A. In this case, we can choose to perform the measurement in A, as this mode is protected up to 10 A and the chance is smaller that the fuse is defective or will go.

Measuring resistance:

The third measurement we perform with the multimeter is the resistance measurement. With this, we can test electrical components for internal short circuits or interruptions. In the images below, two measurements are shown where the resistance of the lamp is determined. The multimeter now functions as an “ohmmeter” and is set as follows:

- The dial is set to the Ω (ohm) position for the resistance measurement;

- The red test lead is inserted into the Ω connection, which is the same connection we use for the voltage measurement;

- The black test lead is again inserted into the COM connection.

The resistance of the lamp is 1.85 ohms. This indicates that the lamp is in order. Note: when the lamp is burning, the resistance changes due to the temperature. We cannot measure the resistance while it’s burning, but immediately after turning it off, the measured value will be significantly lower.

A lamp ages the more hours it has burned. The tungsten wire becomes thinner and evaporates against the inside of the glass. We can see this as the lamp gets darker. A dark-colored lamp will soon fail. In the second measurement, this has happened: the tungsten wire has broken, and the lamp no longer works. The circuit is thereby interrupted. Because the connection is broken, the resistance has become “infinitely” high. The multimeter then indicates OL. Some multimeters display “1.”

With the ohmmeter, we can conduct the following measurements:

- the internal resistance of electrical and non-electrical components;

- locating breaks in an electrical circuit, such as in circuit boards or wiring;

- locating electrical connections using the beep mode;

- locating a ground connection;

- checking if the test leads are in order.

The last measurement is crucial in making a diagnosis. If a test lead is in poor condition, it affects every voltage or current measurement with the multimeter or oscilloscope (the latter can only measure voltage).

If a test cable has once been pinched or has been heavily kinked through intensive use and pulled on, the connection may drop if held at a certain angle. This can be simply checked by holding the ends of the test probes against each other: the resistance should then be about 0.1 ohm. If the resistance is much higher or OL, the test leads are no longer usable.

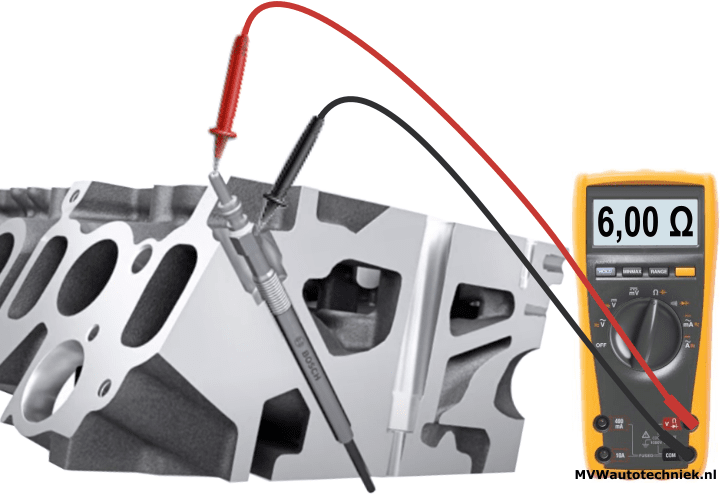

Another example of a resistance measurement is the measurement of the glow plug found in a diesel engine.

- A good glow plug has a resistance of about 6 ohms.

- If the glow plug is broken, the resistance is infinitely high.

- In case of an internal short circuit (the coil and housing make internal contact), we measure (theoretically) a resistance of 0 Ω and actually a resistance of 0.1 Ω due to the “always present” resistance in the test cables, as described in the previous paragraph when checking the test cables.

See the page about the glow plug for more information about operation and measurement techniques.

V4 measurement:

This website describes the voltage levels, signal transmission, and measurement methods of many types of sensors, actuators, ECUs, and networks. These can be found on the pages themselves, such as the temperature sensor, passive, active, and intelligent sensors, relay, and CAN-bus. On these pages, the measurement is specifically about that subject.

In most cases, we use the voltmeter and sometimes the current clamp when tracing faults. We rarely perform the ampere and resistance measurement during a diagnosis:

- To measure the current, the circuit must be interrupted (undesirable), and the current level says insufficient about any losses. The current strength is the same throughout the circuit. Also, the ammeter is limited to 10A. It may sometimes be desirable to use a current clamp not limited to a specific current strength.

- Measuring the resistance is only advisable when determining a connection or interruption. In all other cases, we measure an “unloaded” resistance, and the resistance value is unreliable.

The above means that we almost always use the voltmeter in our diagnosis. In complex diagnoses, we use an oscilloscope, which is also a (graphical) voltmeter. With the voltmeter, we measure voltage differences and losses in a loaded situation, so when the consumer is operational. This makes the measured value the most usable.

To get a handle on voltmeter measurements, it’s helpful to master the V4 measurement. Through four voltage measurements, one can “roughly” find the cause of a poorly functioning or non-working consumer. This paragraph explains how to perform the V4 measurement, what measurement values you can expect, and when there is a fault.

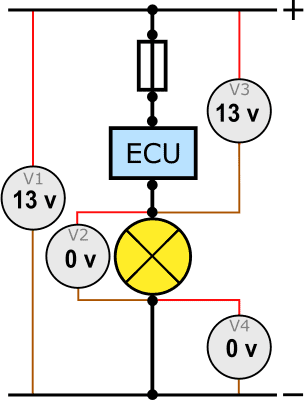

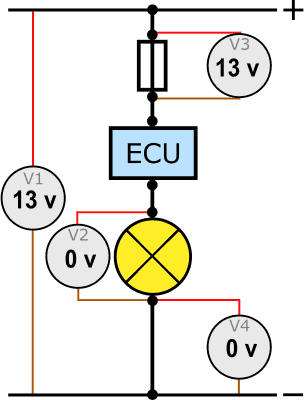

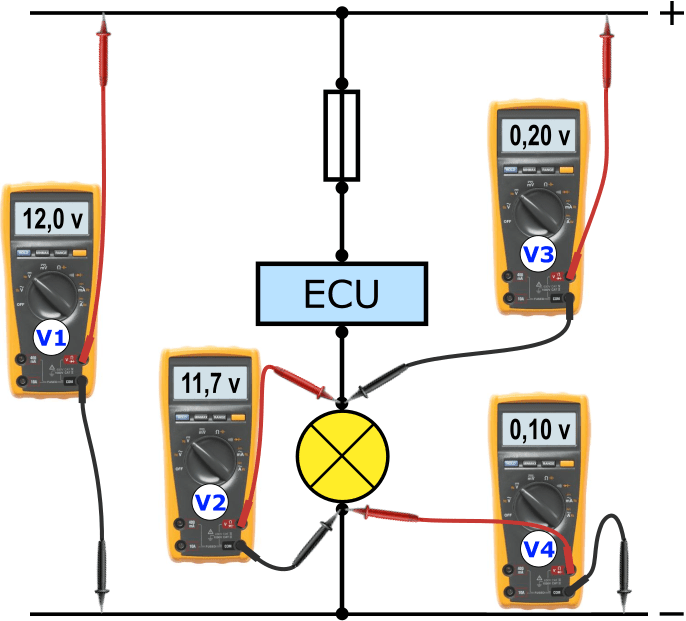

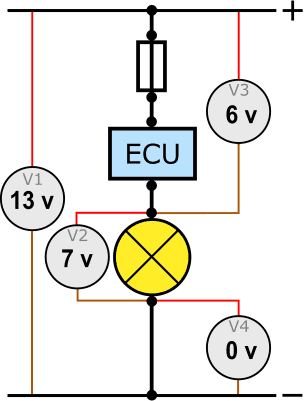

With the V4 measurement, we use one voltmeter and perform a differential measurement at four specific points. We call these four measurements V1, V2, V3, and V4.

Note: with a PWM / duty-cycle controlled consumer, it is not possible to perform this V4 measurement; the oscilloscope must be used!

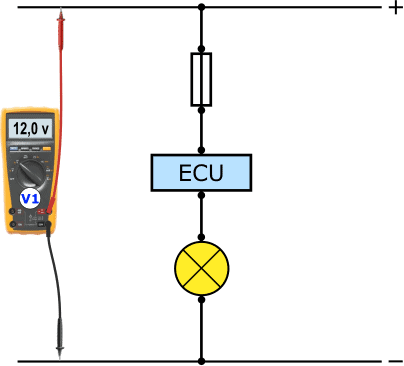

V1:

The V1 measurement is the first one we conduct. Here, we measure the battery voltage. All voltages we measure afterwards are compared to this reading. Before measuring, the consumer must be turned on. For heavy consumers, the battery voltage can drop by a few tenths of a volt without there being a fault. We set the multimeter correctly (see the paragraph about measuring voltage) and hold the test probes on the positive and negative terminals of the battery.

Is it necessary to start the engine during the V4 measurement? Then the V1 measurement will be higher due to the charging voltage from the alternator. Re-conduct the measurement.

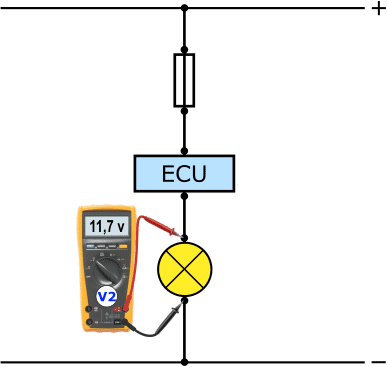

V2:

Next, we measure the voltage difference across the consumer. The consumer must be on. With a lamp, this is not too complicated: we turn on the lamp with a switch. Sometimes activating the consumer can be more challenging, like the electric fuel pump in the tank. In that case, start an actuator test via a diagnostic device or let the engine idle.

- The voltage across the consumer should be almost as high as the battery voltage, with a maximum difference of half a volt. If this is the case, there is no voltage loss in the positive or ground, and the V4 measurement is complete;

- If the voltage in the V2 measurement is more than half a volt lower than the V1 value, there is a voltage loss. In this case, measure the voltages at V3 and V4.

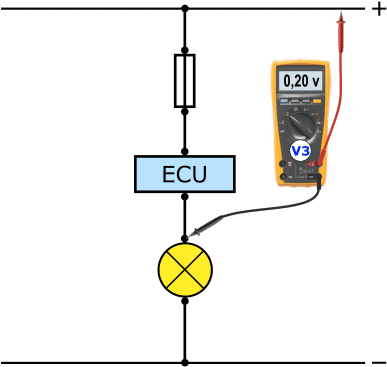

V3:

With this measurement, we determine the voltage loss on the positive side between the positive of the battery and the positive terminal of the lamp.

- The loss may amount to a maximum of 0.4 volts;

- Less than 0.4 volts is acceptable;

- More than 0.4 volts indicates a transition resistance on the positive side.

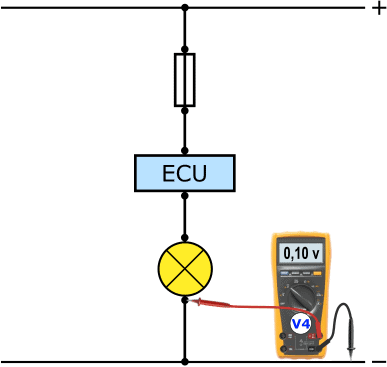

V4:

Finally, we perform the loss measurement between the ground of the lamp and the ground of the battery. The same applies as for the V3 measurement: a maximum loss of 0.4 volts, otherwise there is a transition resistance.

Check:

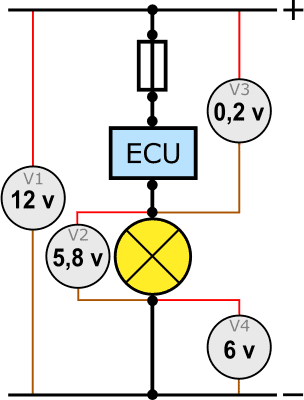

The battery voltage is distributed over the voltage circuit. All partial voltages (V2, V3, and V4) equal the battery voltage (V1). This is visible in the measurements:

- V1 = 12.0 v

- V2 = 11.7 v

- V3 = 0.2 v

- V4 = 0.1 V

With this, we can complete the following formula:

If the calculation deviates significantly, a measurement error has been made. One needs to check which value is not logical. For instance, it is impossible for the lamp to burn at 12 volts while the battery voltage is 13 volts and there is 12 volts of voltage loss.

Below are five possible faults that can be detected with a V4 measurement. To save space and keep it as clear as possible, the images of the “real” voltmeters have been replaced by a circle with the number in it.

Fault 1 – lamp shines dimly:

The lamp shines less brightly than other lamps in the vehicle. Logically, because it’s burning at only 7 volts instead of 13 volts. The outcome of V3 shows that there is a 6-volt loss on the positive side. Between the positive of the battery and the positive of the lamp, there is a transition resistance where 6 volts are used. This voltage loss reduces the voltage with which the consumer operates.

Possible causes:

- a damaged wire for the fuse, between the fuse and the ECU or between the ECU and the lamp;

- a poor connection of the fuse in the fuse holder;

- a poor wire connection or connectors at one of the black dots in the diagram;

- a defect in the ECU.

To determine where the transition resistance is, move the negative test lead of the V3-meter to the underside of the ECU. If you still measure 6 volts here, the voltage has not been lost in this wire, and the cause is higher. However, if you measure 0 volts above the wire, this wire is damaged and needs to be replaced.

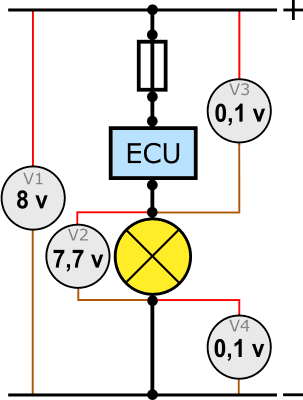

Fault 2 – lamp shines dimly:

Again, we have a lamp that shines less brightly than the rest. In the measurements, we see there is a voltage loss of 6 volts in measurement V4. Also, in this case, 6 volts are needed to overcome the transition resistance in the ground.

Possible causes:

- a damaged wire between the lamp and a ground point;

- corrosion between the contact points of the cable eye and the ground point.

If the transition resistance is in the wire, mounting a new wire between the lamp and a ground point suffices. If the wire is fine, help can be obtained by unscrewing and sanding the ground connection, then thoroughly cleaning and remounting the wire, and measuring again.

Fault 3 – lamp shines dimly:

All lamps shine dimly. When performing the measurement, we see that the battery voltage (V1) is too low. The loss measurements (V3 and V4) are fine. Charging (and perhaps testing) the battery is sufficient to solve the problem.

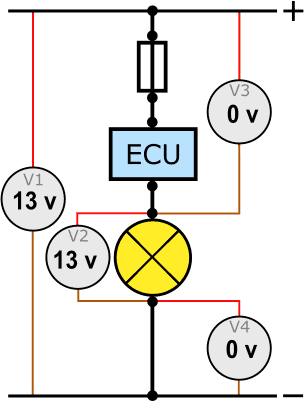

Fault 4 – lamp does not light:

The lamp does not light. However, the voltage across the lamp is 13 volts and there is no loss.

Possible causes:

- lamp is defective: due to a broken filament, the circuit is interrupted. The 13 volts of voltage and the ground still reach the lamp, so we do measure a “good” voltage difference at V2;

- poor connector connection due to the metal connectors losing their grip force. With frequent unplugging and pressing of the connector onto the lamp, space can arise between the metal plug and the lamp connection.

A defective lamp can often be judged optically. The filament is visibly broken. Optionally, we measure the resistance of the lamp with the ohmmeter. An infinitely high resistance indicates an interruption.

Fault 5 – lamp does not light:

Once again, we have a lamp that does not light. The voltage difference we expect to measure at V2, we now measure at V3. This means that there is a good plus at the top of the fuse and a good ground at the bottom. Based on the measurement value, the fuse now seems like a consumer that uses the 13 volts, but this is incorrect.

The cause of this fault is a defective fuse. Just like in the previous fault, where the broken filament caused an interrupted circuit, here the fuse causes the circuit to be interrupted.