Introduction:

The hybrid or fully electric car has larger, heavier batteries than cars with only an internal combustion engine. In hybrid cars, high voltages are used, which can be life-threatening during repairs by unqualified personnel. For example:

- A starter motor in operation uses around 1.2 kW (1200 Watts)

- A hybrid car running entirely on electricity uses around 60 kW (60,000 Watts)

Only people who have followed a special training may work on hybrid cars. There is a 12-volt onboard network for the power supply of accessories (like radio, etc.) with its own small battery, and a high-voltage onboard network that operates at 400 volts (depending on the brand). The 400 v voltage is converted to 12 v by a special DC/DC converter, charging the respective battery.

High demands are placed on hybrid drive batteries. They must have a very large storage capacity. Large energy reserves are stored, and very high voltages are drawn when supporting the internal combustion engine (hybrid), or when delivering energy for the complete drive (BEV).

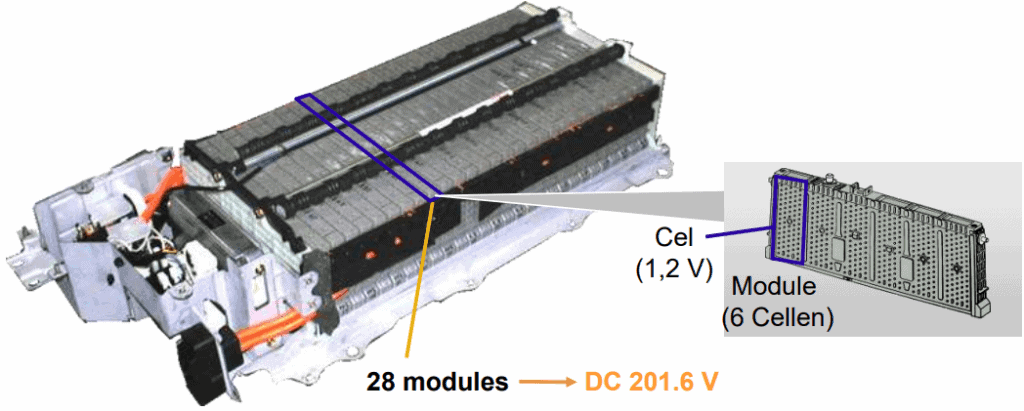

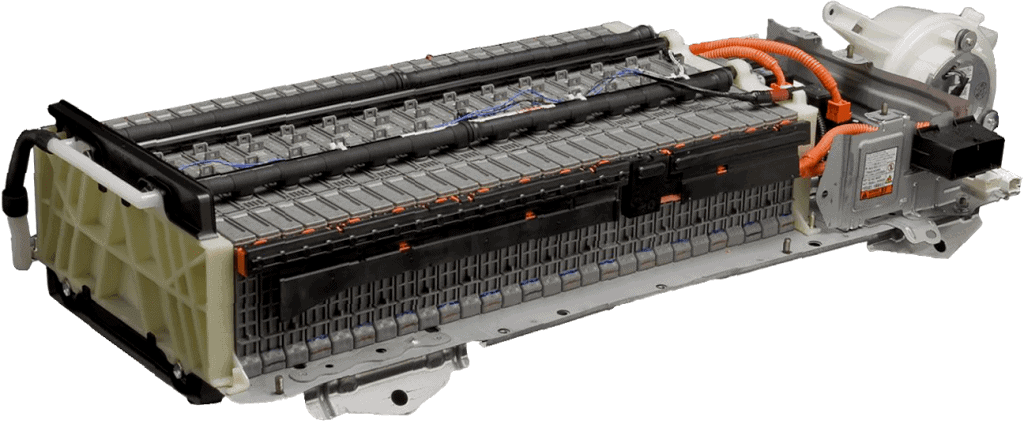

The image below shows a battery pack from a Toyota Prius. This Nickel Metal Hydride (NiMH) battery contains 28 modules, each consisting of 6 cells. Each cell has a voltage of 1.2 volts. The total voltage of this battery pack is 201.6 volts.

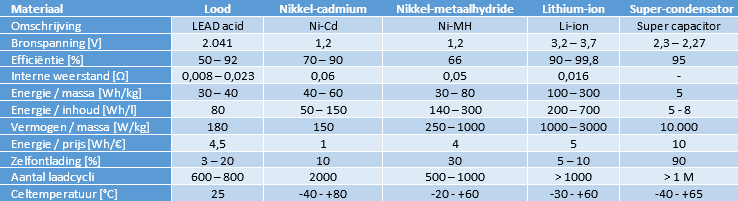

Materials and specifications of different types of batteries:

When developing the electric powertrain, a choice is made between different types of batteries. The characteristics, performance, construction possibilities, and costs play a major role. The most common types of batteries used in hybrid and fully electric vehicles are the Ni-MH (nickel-metal hydride) and the li-ion (lithium-ion) batteries.

In addition to the Ni-MH and li-ion types, there is a development of electrolytic capacitors, which we categorize as “supercapacitors,” or “supercaps.”

The table shows the materials of different batteries with their specifications.

Lead-acid battery:

The lead-acid battery is also mentioned in the table (gel and AGM versions are not considered). Due to its highest lifespan at a discharge of a maximum of 20%, aging issues with sulfation, and low energy density and content, it is not suitable for use in electric vehicles. However, the lead-acid battery is still found as an accessory battery; the low-voltage consumers such as lighting, comfort systems (body), and infotainment operate at a voltage of around 14 volts.

Nickel-cadmium (Ni-Cd):

In the past, Ni-Cd batteries were affected by a memory effect and for this reason are unsuitable for use in electric drives: constant partial charging and discharging occur. Modern Ni-Cd batteries have almost no issues with the memory effect anymore. The biggest disadvantage of this type of battery is the presence of the toxic substance cadmium, making the Ni-Cd battery extremely environmentally unfriendly. Therefore, using this battery is legally prohibited.

Nickel-metal hydride (Ni-MH):

The Ni-MH battery charges faster than a lead-acid battery. During charging, both heat and gas are generated, which must be dissipated. The batteries are equipped with a cooling system and venting valve. Thanks to their long lifespan and high energy and power density, Ni-MH batteries are suitable for use in electric vehicles. However, this type of battery is sensitive to overcharging, excessive discharges, high temperatures, and rapid temperature changes.

The image below shows the Ni-MH battery pack of a Toyota Prius. This battery pack is located in the trunk, behind the rear seat backrest. When the temperature sensors register a high temperature, the cooling fan is activated (visible in the photo on the right side as the white housing). The fan draws air from the interior and blows it through the air ducts in the battery pack to cool the cells.

Lithium-ion (li-ion):

Due to the high energy and power density of the lithium-ion battery (compared to Ni-MH), a li-ion battery pack is usually used in plug-in hybrids and fully electric vehicles. The li-ion battery performs well at low temperatures and has a long lifespan. The expectation is that properties will improve in the coming years thanks to ongoing development.

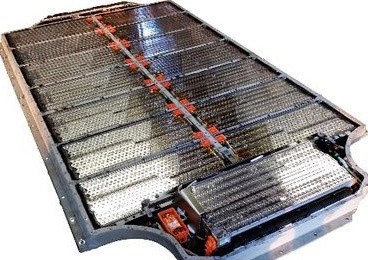

The next image shows the (li-ion) battery pack of a BMW i3. The cover has been unscrewed and is placed behind it. In assembled condition, the cover seals airtight.

The i3’s battery pack is mounted under the vehicle. The floor space between the front and rear axles is used as much as possible to provide as much space as possible for the battery pack.

In the image, we see the eight separate blocks with twelve cells each. Each block has a capacity of 2.6 kWh, totaling 22 kWh. For comparison, the current generation i3 (as of 2020) has a battery with a capacity of 94 Ah and a power of 22 kWh. The size of the battery pack has remained the same since its introduction in 2013, but the performance (and thus its range) has greatly improved.

Tesla uses small battery cells in models from 2013 onwards (Model S and Model X) that are slightly larger than the standard AA batteries we know from the TV remote. The battery cells (18650 from Panasonic) are 65 mm long and have a diameter of 18 mm. The most extensive battery packs contain no fewer than 7104 of these cells.

In the images below, we see the individual battery cells on the left and a battery pack containing the 7104 cells on the right.

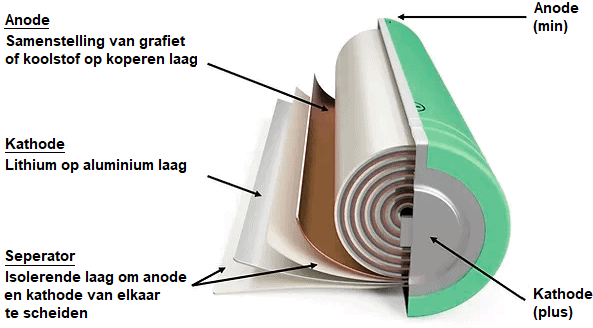

The lithium-ion battery consists of four main components:

- The cathode (+) made of a lithium alloy

- The anode (-) made of graphite or carbon

- The porous separator

- The electrolyte

During discharge, the lithium ions move through the electrolyte from the anode (-) to the cathode (+), to the consumer, and back to the anode. During charging, the ions move in the opposite direction, from the cathode (+) to the anode (-).

The electrolyte contains lithium salts to transport the ions. The separator ensures that the lithium ions can pass through, while the anode and cathode remain separated.

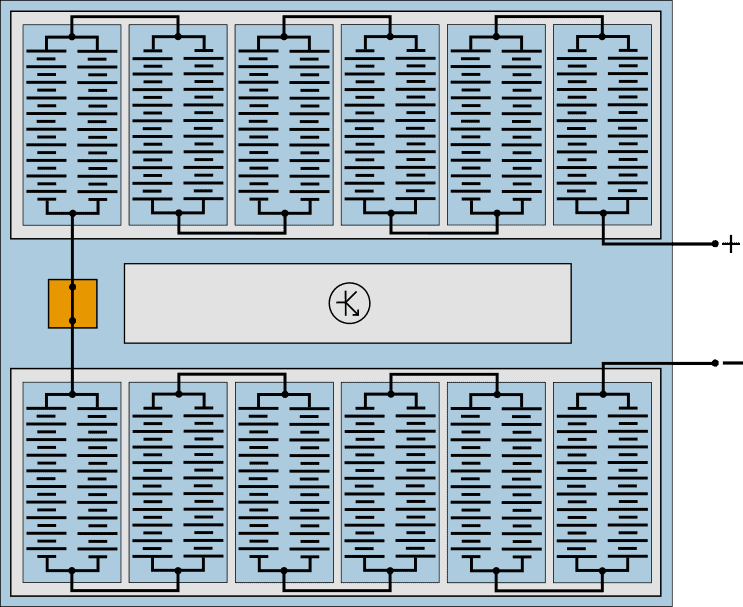

The battery cells are housed in modules, which are connected in series with each other. The schematic representation below shows a battery pack that has strong similarities with that of a Volkswagen E-UP! and Renault Zoe. The only difference is the number of cells: the battery pack of the E-UP! has 204 cells and that of the Renault Zoe 192.

In this example, the battery pack consists of two packs of six modules. Each module contains two parallel-connected groups of 10 series-connected cells.

- Series connection: the battery voltage increases. With a cell voltage (li-ion) of 3.2 volts, one battery module delivers (3.2 * 10) = 32 volts.

The disadvantage of a series connection is that with a bad cell, the capacity of the entire series connection decreases. - Parallel connection: the voltage remains the same, but the current and capacity increase. A bad cell does not affect the cells in the parallel-connected circuit.

Manufacturers can therefore choose to apply multiple parallel connections per module. In the modules of the Volkswagen E-Golf, not (as in this example two), but three groups of cells are connected in parallel.

Lithium-ion cells have a lifespan of about 2000 discharge and charge cycles before their capacity is reduced to about 80% of their initial charge capacity.

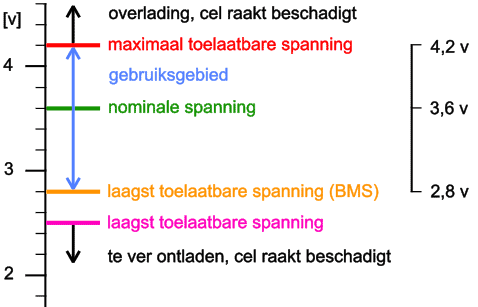

The voltages of a li-ion cell are as follows:

- Nominal voltage: 3.6 volts;

- Discharge limit: 2.5 volts;

- Maximum charge voltage: 4.2 volts.

Most Battery Management Systems (BMS) maintain a lower limit of 2.8 volts. If the cell is discharged further than 2.5 volts, it becomes damaged. The lifespan of the cell is shortened. Overcharging the li-ion cell also reduces its lifespan and is dangerous. Overcharging the cell can make it flammable. The temperature of the cells also affects lifespan: at temperatures below 0°C, the cells may no longer be charged. A heating function provides a solution in this case.

Supercapacitor (supercap):

In the previous sections, various battery types have been mentioned, each with their applications, advantages, and disadvantages. One disadvantage everyone faces with such a battery is the charging time. Charging a battery pack can take several hours. Fast charging is an option, but this involves more heat and possibly faster aging (and damage) of the battery pack.

Currently, a lot of research and development is taking place into supercapacitors. These are also referred to as “super caps” or “ultracapacitors.” The application of supercaps could offer a solution for this:

- Charging is very fast;

- They can discharge energy very quickly, thus a significant power increase is possible;

- More durable than a li-ion battery thanks to an unlimited number of charge cycles (at least 1 million) as no electrochemical reactions occur;

- In light of the previous point, a supercap can be fully discharged without any harmful effects on lifespan.

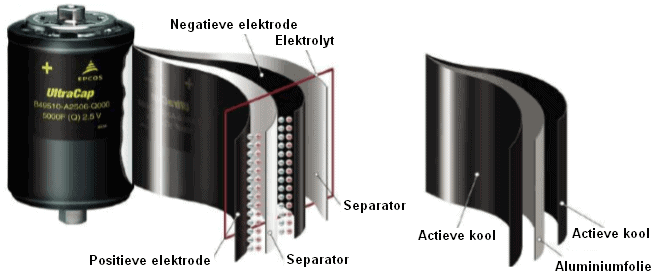

Supercaps are capacitors with a capacity and energy density thousands of times higher than standard electrolytic capacitors. The capacity is increased by using a special electrolyte (insulation material) containing ions and thus has a very high dielectric constant between the plates. A separator (a thin film) is soaked in a solvent with ions and placed between the plates. The plates are usually made of carbon.

The shown capacitor has a capacity of 5000 F.

With supercaps, a combination can be made with a li-ion HV battery; during short-term acceleration, the energy from the capacitors can be used instead of the energy from the HV battery. During regenerative braking, the capacitors recharge fully within a fraction of a second. Future developments may also make it possible to replace the li-ion battery with a supercap pack. Unfortunately, with current technology, the capacity and thus the power density are too low compared to a lithium-ion battery. Scientists are looking for ways to increase both capacity and power density.

Battery cell balancing:

Through passive and active battery cell balancing, each cell is monitored by the ECU to maintain a healthy battery status. This extends the lifespan of the cells by preventing deep discharge or overcharge. Especially lithium-ion cells must remain within strict limits. The cell voltage is proportional to the state of charge. The charge of the cells should be kept as balanced as possible. With cell balancing, it is possible to regulate the state of charge to an accuracy of 1 mV (0.001 volts).

- Passive balancing ensures equilibrium in the state of charge of all battery cells by partially discharging the cells with a too high state of charge (this will be discussed further in the paragraph);

- Active balancing is a more complex balancing technique that can control the cells individually during charging and discharging. The charging time with active balancing is shorter than with passive balancing.

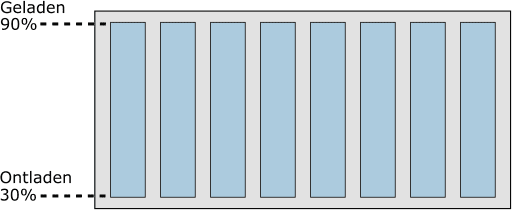

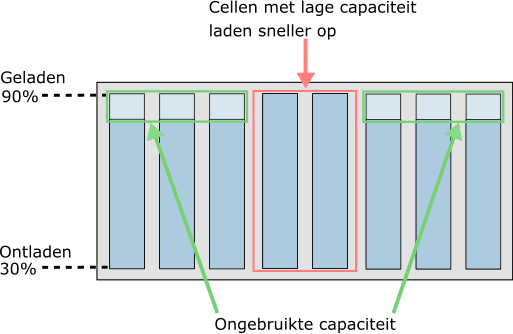

The next image shows a battery module with eight cells.

The eight cells are charged up to 90%. The lifespan of a cell decreases if it is continuously charged to 100%. Conversely, lifespan also decreases if the battery discharges beyond 30: below 30% state of charge, the cell is deeply discharged.

Therefore, the state of charge of the cells will always be between 30% and 90%. This is monitored by the electronics but is not visible to the vehicle driver.

The digital display on the dashboard indicates 0% or 100% upon reaching 30% or 90%.

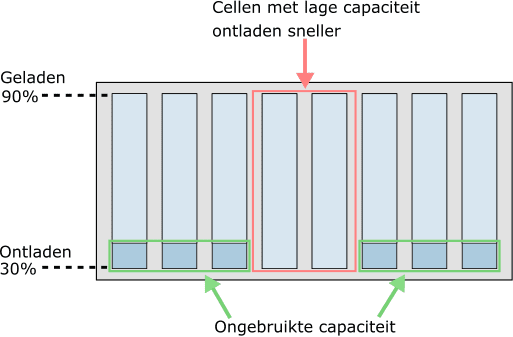

Due to aging, some cells can become weaker than others. This greatly impacts the state of charge of the battery module. The following two images show the state of charge when two cells have a lower capacity due to aging. These battery cells are unbalanced in these situations.

- Discharging faster due to poor cells: the two middle cells are discharged more quickly due to their lower capacity. To prevent deep discharge, the other six cells in the module cannot provide more energy and can therefore no longer be used;

- Not fully charging due to poor cells: due to the low capacity of the middle two cells, they are fully charged more quickly. Since they reach 90% faster than the other six cells, further charging is not possible.

It is clear that cells with lower capacity are the limiting factor in both discharging (while driving) and charging. To optimally use the full capacity of the battery pack and for a long lifespan.

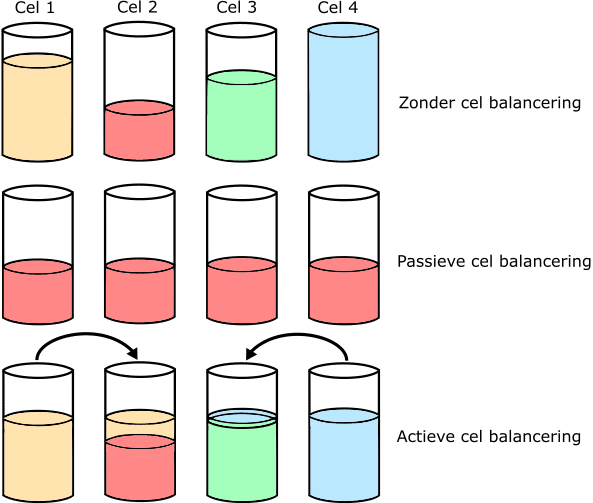

There are two methods for battery balancing: passive and active.

- Without balancing: four cells each have a different state of charge. Cell 2 is almost empty, and cell 4 is fully charged;

- Passive: the cells with the most capacity are discharged until the state of charge of the weakest cell (in the example cell 2) is reached. The discharge of cells 1, 3, and 4 is a loss.

In the example, we see that the cups are discharged until they reach the state of charge of cell 2; - Active: the energy from the full cells is used to fill the empty cells. There is now no loss, but a transfer of energy from one cell to another.

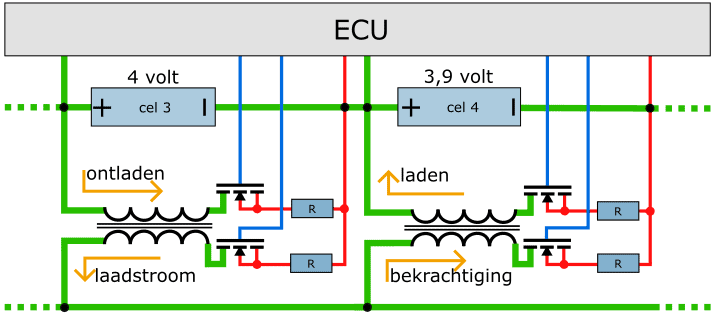

Below, the principle of passive and active cell balancing is explained.

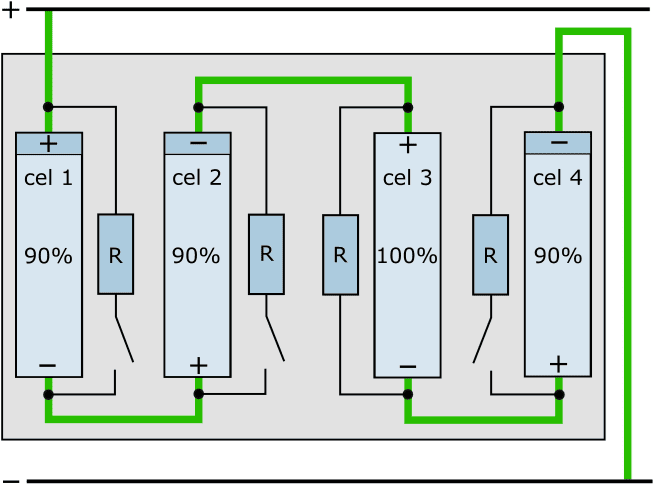

Passive cell balancing:

In the example, we see four series-connected battery cells with a switchable resistor (R) in parallel with them. The resistor is switched to ground with the switch in this example. In reality, this is a transistor or FET.

In the example, we see that cell 3 is charged to 100%. We know from previous sections that this cell charges faster because it is weaker than the other three. Because the state of charge of cell 3 is 100%, the other three cells are no longer charged.

The resistor that is parallel to cell 3 is involved in the circuit by the switch. Cell 3 discharges because the resistor absorbs voltage as soon as current flows through it. The discharge continues until the cell is at the level of the other cells; in this case, 90%.

When all four cells in this module have the same state of charge, they can be further charged.

With passive cell balancing, energy is lost: the voltage absorbed by the parallel-connected resistors is essentially lost. Nevertheless, many manufacturers still use this method of balancing to this day.

Active cell balancing:

Active cell balancing is obviously much more efficient. Here, the energy from the too-full cell is used to charge the empty cell. An example of active cell balancing is shown below.

In the example, we see two series-connected cells (3 and 4) with their voltages (4 and 3.9 volts, respectively). Cell 3 is discharged using the transformer. The FET on the primary side enables discharge. The primary coil in the transformer is thus charged. The FET on the secondary side engages the secondary coil of the transformer. The obtained charge current is used to power the transformer under another cell. The transformer under cell 4 is similarly switched on and off by FETs.