Introduction:

The HV system in vehicles with an electrified or fully electric drive is equipped with multiple protections. The system can only be activated once all safety requirements are met. When a fault is detected, the HV system immediately shuts down. This can occur in the following situations:

- An HV system component is dismantled, and the system is activated.

- Due to a collision or water damage, electrical components or wiring short circuit with each other or with the ground.

- Components are damaged due to overload.

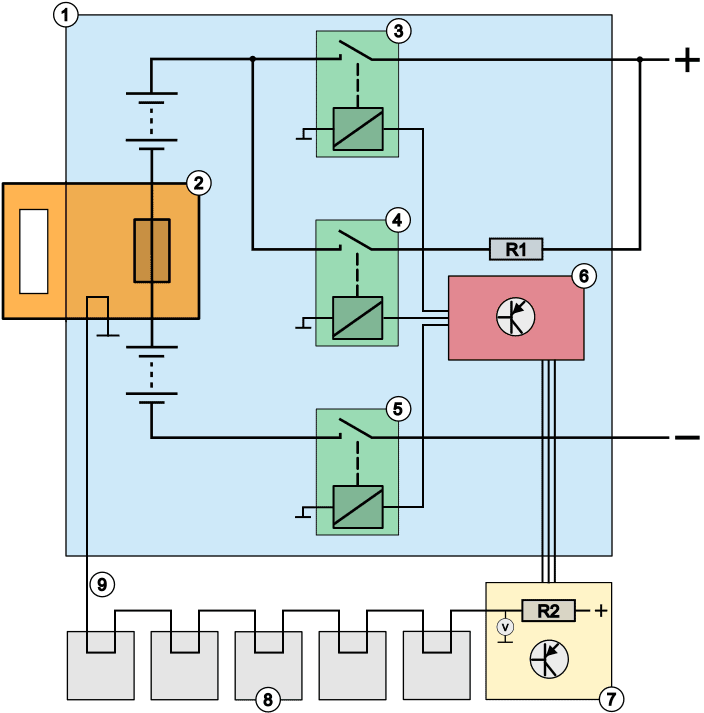

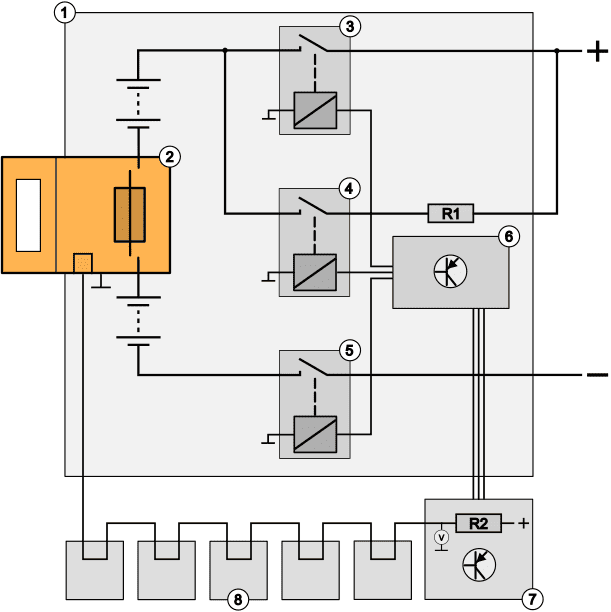

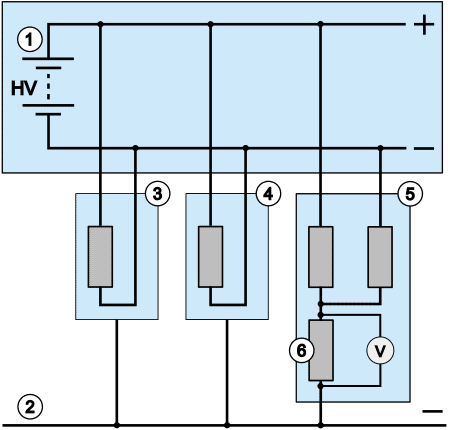

The image below shows the components that are part of the protection system. A section of the HV battery (1) is shown in blue, with the orange service plug (2) on the left. In the middle are three relays (3 to 5), which are activated one by one by the ECU (6). Below the HV battery is the ECU (7), which connects to the consumers (8), such as the electric motor, PTC heater, air conditioning compressor, power steering, and charging device.

Legend:

- HV battery

- Service plug with fuse

- Relay 1

- Relay 2

- Relay 3

- ECU of HV battery

- ECU of HV system

- Electric consumers

- Interlock wire

Activating the HV System:

The driver activates the HV system by pressing the start button. The system is activated once the “HV ready” message appears on the display. Before the HV system is active, the relays in the HV battery pack are controlled to connect the battery pack to the consumers.

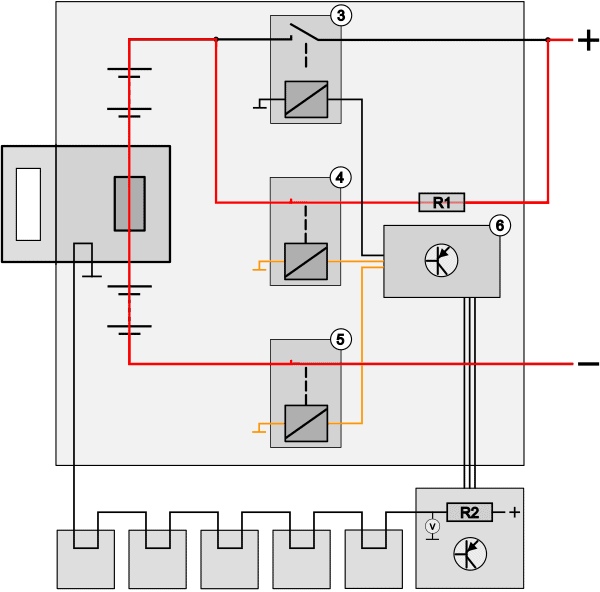

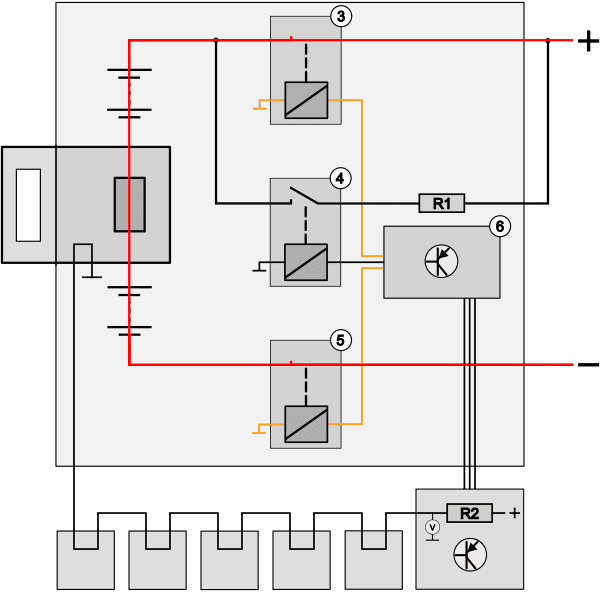

When the HV system is activated, the ECU (6 in the image below) activates the HV relays in the positive circuit (relay 4) and the ground circuit (relay 5). First, the current circuit is activated on the positive side via a resistor. In the image below, relay (4) allows current to flow to resistor R1. The resistor limits the current passing through, thus restricting the inrush current. This allows the capacitors in the inverter to charge slowly. At this point, the system can perform a safety check at a lower voltage. Once the voltage across the capacitors in the inverter approximately equals the voltage of the HV battery pack, relay 3 closes, and relay 4 opens, bringing the full voltage to the inverter and other electrical components.

Interlock:

The interlock system provides protection against electrical contact when there are open connections. Each component connected to the HV battery includes at least one contact capable of disabling the HV system upon disruption. These contacts may be integrated into the wiring or as a switch in a component housing.

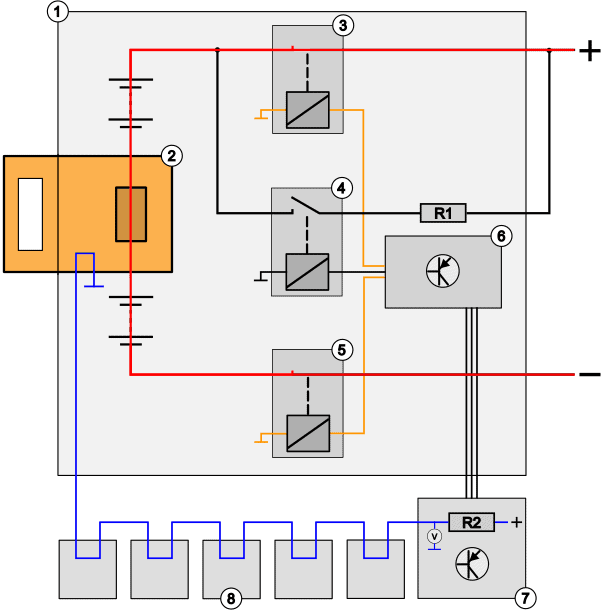

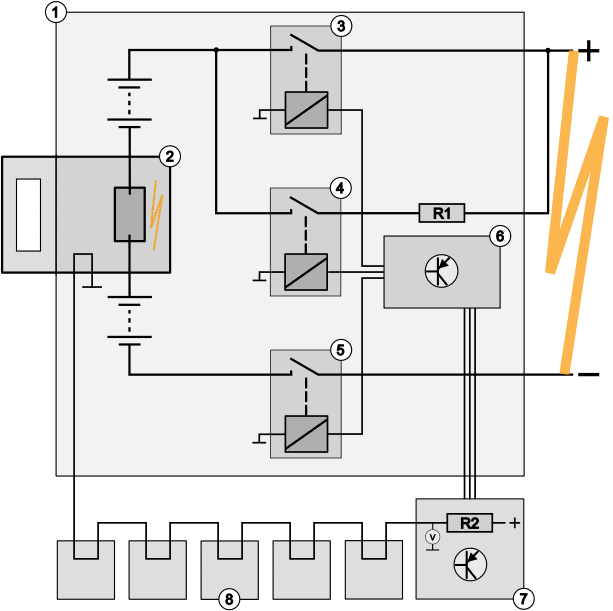

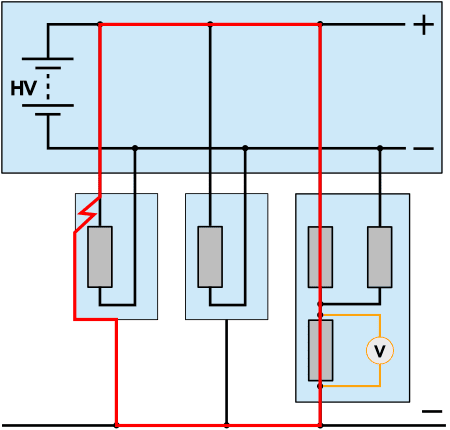

The image at the bottom left shows the active system: relays 3 and 5 are closed, meaning the voltage from the HV battery is being passed to the consumers. The interlock circuit, shown in blue, extends from the vehicle ECU (7). From the ECU, a voltage on resistor R2 is applied. The interlock is channeled as a series circuit through the electric consumers (8). In the battery pack, the interlock is connected to ground. Between resistor R2 in the ECU (7) and the outlet to the consumers, there is a branch where the voltage on the interlock is measured.

- Interlock intact: voltage after resistor R2 is 0 volts;

- Interlock interrupted: the voltage is not consumed in resistor R2 and is (depending on the supply voltage) 5, 12, or 24 volts.

The voltage after resistor R2 is continuously monitored during activation and while driving.

When the service plug (2) or one of the electrical components (8) is dismantled, the interlock circuit is also interrupted. This situation is visible in the right image above, where the service plug is displaced. Both the fuse between the battery modules and the interlock circuit are interrupted. Since the interlock is no longer connected to the vehicle ground, the voltage after resistor R2 rises to the value of the supply voltage. The vehicle ECU (7) immediately commands the battery ECU (6), causing relays 3, 4, and 5 to deactivate. The HV system is then shut off.

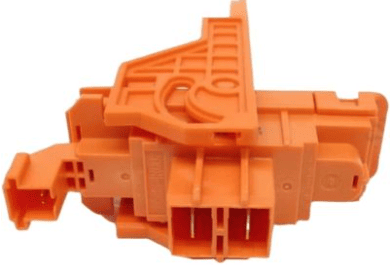

The image shows the orange service plug with large contacts in the middle to connect the positive and negative lines of the HV battery, and to the left, a smaller connector with two pins. These are the two pins of the interlock. These connections are also found on connectors of HV components.

Short Circuit Protection:

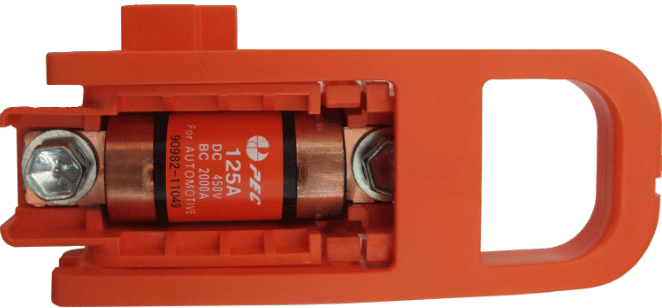

The HV system must be protected against excessive currents, which can result from short circuits in the wiring or electrical components. Without protection, this can lead to an arc, melting of lines, or even fire. A fuse is designed to protect the system against these hazards. The fuse may be located in the service plug or elsewhere in the battery pack. Vehicles may also be equipped with multiple fuses, each designed to protect a specific circuit.

In addition to protecting the system from excessive currents, the current sensor in the positive or negative line of the HV battery transmits the current to the ECU. The ECU decides to deactivate the relays in the event of an overload.

Permanent Isolation Monitoring:

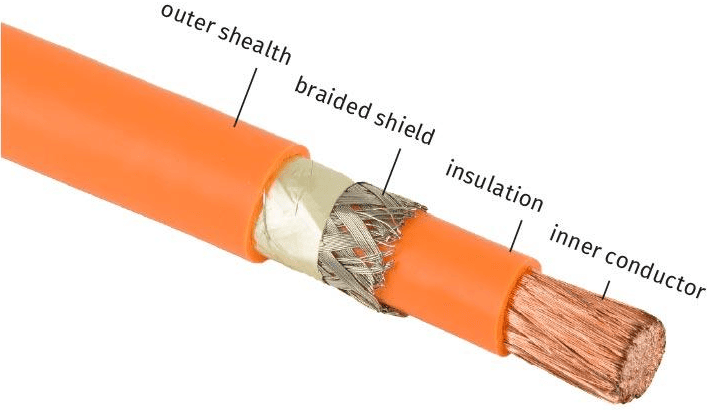

The positive and negative sides of the HV battery do not come into contact with each other or the environment. The positive side (from the + battery to the + of the inverter) is wrapped in multiple layers of insulation with a braided shield in between. The negative side is also insulated and does not contact the vehicle body or component casing. The vehicle chassis, however, is connected to the negative side of the on-board battery (12 volts in passenger cars). This is not the case in the HV section. Causes of a fault may include:

- After a collision, there may be damage to the wiring, causing the copper of the positive and negative wires to contact each other or the vehicle chassis;

- Due to overload – and subsequent overheating – insulation in an electrical component may become defective (melted), allowing contact with the environment;

- Or there may be a conductive liquid caused by the vehicle being submerged in water, cooling fluid leakage in the HV battery pack causing a short circuit between the positive and negative, or refrigerant leakage in the electric air compressor enabling conduction.

In the electrical components, poor insulation can create a connection between the positive or negative leads from the HV battery and the housing. Since the housing is typically mounted on the vehicle chassis, without the intervention of protections, a current could flow in the case of poor insulation. The moment the positive side of the HV battery – due to an isolation fault – connects via the housing to the vehicle chassis, high voltage of hundreds of volts is present on the chassis. However, because there is no way to connect to the negative side of the HV battery, nothing will happen because no current will flow. It will only become problematic if there are multiple insulation faults where both the positive and negative sides of the HV battery make contact with the chassis.

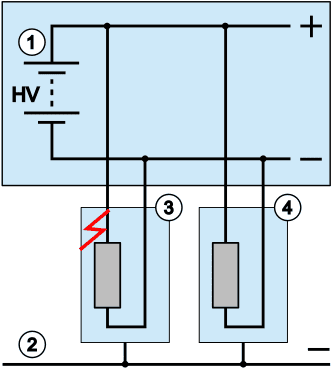

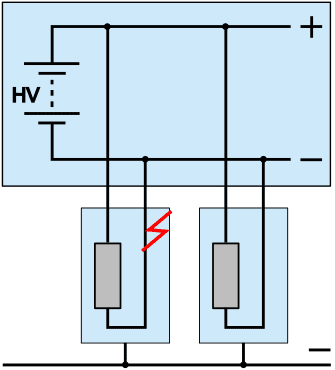

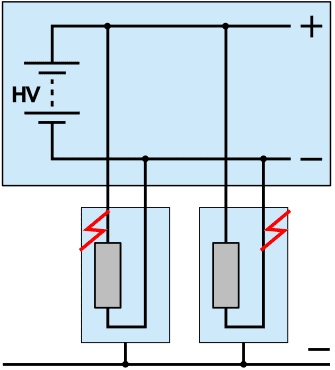

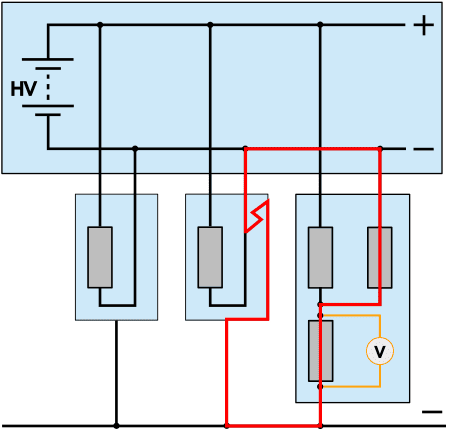

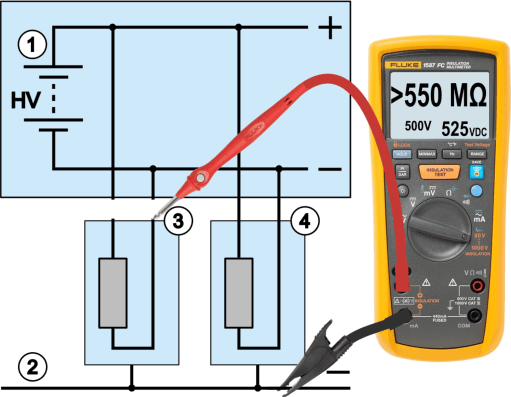

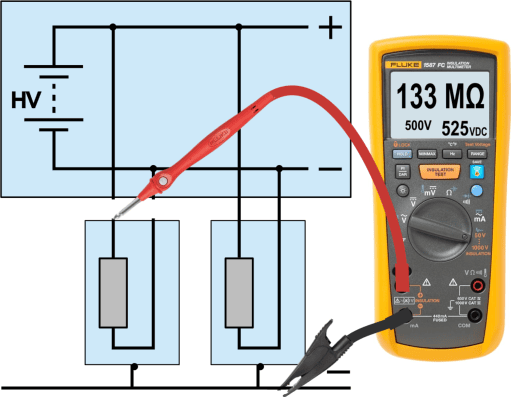

The three images below show the HV battery pack (1) with the positive and negative leads, with the vehicle chassis (2) at the bottom and in between two electric consumers (3 and 4).

- Poor insulation positive side component: when there is poor insulation between the positive and the housing in a consumer (e.g., the electric heater), the housing will become energized. Because there is no connection to the negative side of the HV battery, no current flows;

- Poor insulation negative: there will also be (a small) voltage on the chassis, but no current will flow;

- Poor insulation in both the positive and negative: in this situation there is a short circuit between the positive and negative of the HV battery. The chassis becomes the connection between positive and negative. The current will rapidly increase until the fuse in the service plug and/or the HV battery blows to protect the system.

Since a poor insulation in the positive or negative still does not create a closed circuit, the fuse in the service plug will not blow. The permanent isolation monitoring in electric vehicles detects such current transfer, warning the driver through a fault message. The vehicle can still function with an insulation fault, unless the manufacturer has it shut down via software.

Number 5 in the image below indicates the component where permanent isolation monitoring takes place. In reality, this electrical part is, of course, more complex.

Number 6 indicates the measurement resistance over which the voltage drop is measured.

The two images below illustrate situations with poor insulation on the positive (left) and negative (right). As current flows through the measurement resistance, voltage is consumed in the resistance circuit. The voltage drop across the measurement resistance indicates the amount of current flowing through the resistances.

As soon as the ECU with permanent isolation monitoring detects an anomaly, it stores a fault code. Possible descriptions for the P-codes (such as P1AF0 and P1AF4) include: “battery voltage system isolation lost” or “battery voltage isolation circuit malfunction”. When a vehicle enters the workshop with an insulation fault, the technician can measure the insulation resistances using diagnostic equipment or manually with a Megohmmeter to check for any insulation leaks.

Diagnosis with the Megohmmeter:

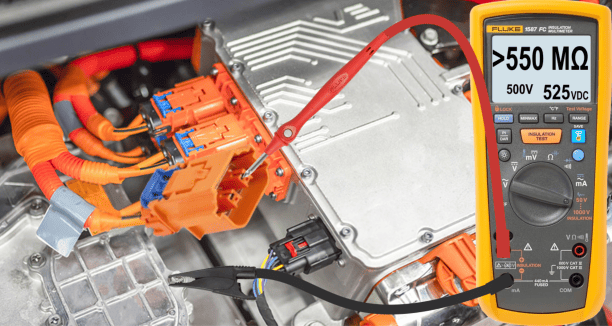

The previous paragraph explained the concept of “insulation resistance” and showed how the vehicle monitors for leaks from the positive or negative connections from the HV battery to the vehicle chassis using permanent isolation monitoring. This section delves deeper into how a technician locates the fault using a Megohmmeter. Technicians must be certified to work on HV systems. The software in a diagnostic tester can perform an isolation test for certain brands, for components that only show an insulation fault after activation, such as electric heaters or electric air conditioning.

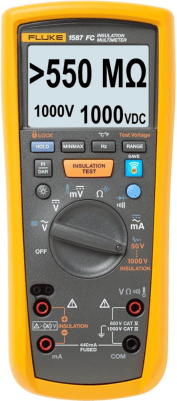

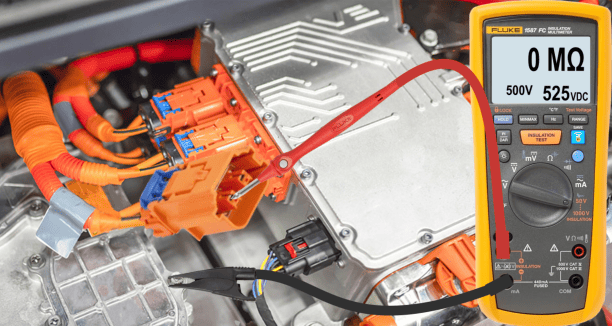

In other cases, we can measure the insulation resistance with a Megohmmeter. A regular multimeter cannot measure insulation resistance because its internal resistance can reach up to 10 million ohms. This internal resistance is too high to measure large resistance values. A Megohmmeter is suitable for this and can output a voltage from 50 to 1000 volts to simulate operating conditions. This high voltage ensures that the current even finds its way through the smallest damages in the insulation via the copper core to the insulation. To measure with the Megohmmeter, set the meter to the same voltage as the HV battery or one step higher. After connecting the measurement cables and correctly setting the meter, press the orange “insulation test” button. The set voltage (in the image: 1000 volts) is applied to the measurement cables and thus to the component, and then we read the ohmic value from the display.

- An insulation resistance greater than 550 MΩ (Megaohm, which means 550 million ohms) is in order. This is the maximum measurement range;

- A value lower than 550 MΩ may indicate an insulation leak, but that might not always be the case;

- According to the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), the insulation resistance of an EV should be at least 500 Ω per volt. With a nominal HV voltage of 400 volts, the resistance should be (500 Ω * 400 v) = 200,000 Ω.

- Manufacturers often set higher quality and safety standards, leading to higher minimum insulation resistances. Therefore, factory instructions must always be followed during diagnostics.

Factory specifications describe the steps, safety instructions, and minimum insulation resistances.

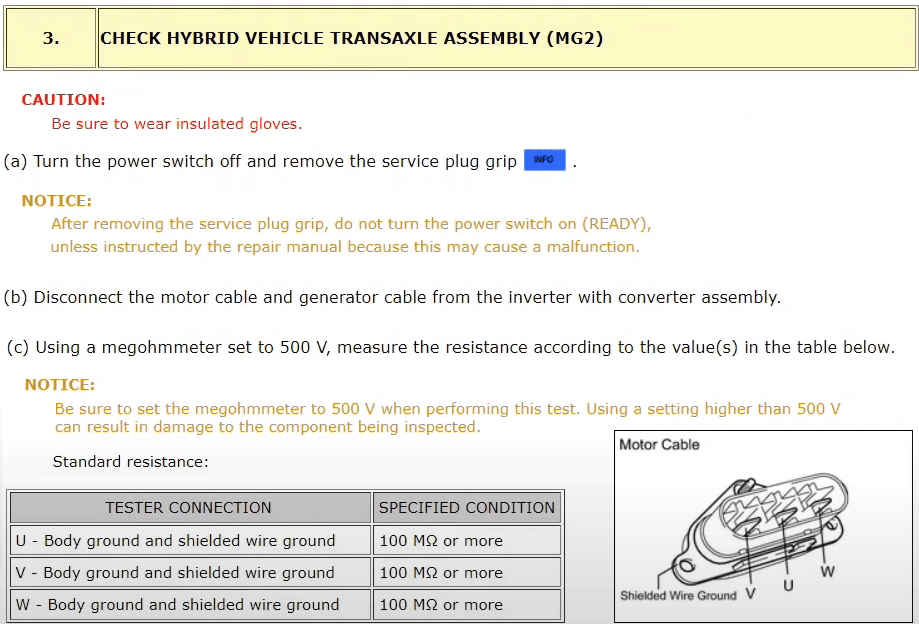

The following image shows a screenshot from a Toyota manual. For the model in question, the minimum insulation resistances of the cables to the electric motor are shown.

The megohmmeter should be set to 500 volts, and the minimum resistances of the wiring (U V and W) to the motor in relation to the casing should be 100 MΩ (MegaOhm) or more.

The insulation resistances of components like the electric air conditioner compressor and heating element may differ. Refer to the factory data for measurements on other components.

1. Insulation Measurement on the Negative Side (No Fault):

With the disconnected plug, we also measure the negative side relative to the vehicle ground. Images 1 and 2 show how this measurement looks schematically and in reality. The measurement results in an insulation resistance of >550 MΩ, indicating the insulation is in good condition.

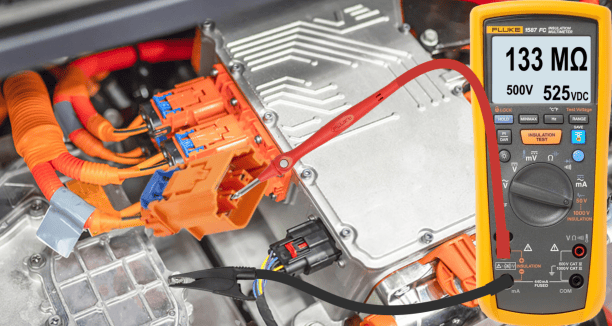

2. Insulation Measurement on the Positive Side (No Fault):

After disconnecting the plug, for example, from the inverter, we attach the red probe to the pin in the disassembled plug (now in the positive side) and the black probe to a ground point connected to the vehicle chassis. Image 1 restates the schema from the previous paragraph, with the HV battery (1), vehicle ground (2), and two consumers (3 and 4) numbered. The Megohmmeter is connected, and the orange “insulation test” button has been pressed to measure the insulation resistance with the transmitted voltage of 500 volts. This measures 133 Megaohm. The insulation resistance is lower than the previous measurement. Manufacturer guidelines should be consulted. We adhere to the minimum insulation resistance of 100 MΩ specified by the manufacturer. The insulation resistance is acceptable.

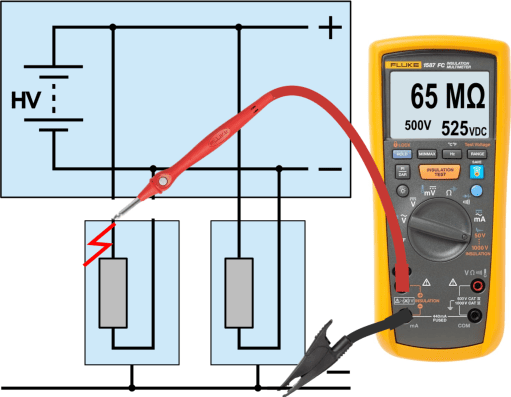

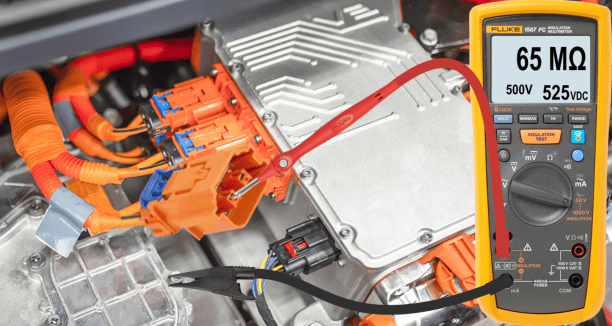

3. Insulation Measurement on the Positive Side (Fault):

During the same connections, we measure an insulation resistance of 65 MΩ. Although the resistance value is higher than the minimum 500 ohms per volt set by the IEC and IEEE (see previous paragraph), the wiring and/or component are rejected because the manufacturer prescribes a minimum resistance value of 100 MΩ. The wiring and/or plug connections must not be repaired but should be completely replaced.

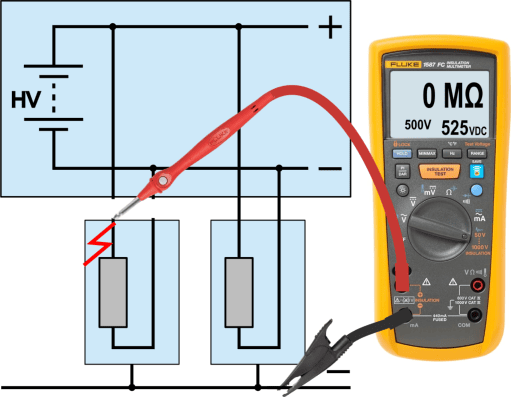

4. Insulation Measurement on the Positive Side (Fault):

When an insulation value of 0 MΩ is measured, there is a direct connection (short circuit) between the HV wire and the casing. The wiring and/or plug connections must not be repaired but should be completely replaced.

In the event of an insulation fault, connectors of other consumers can be disconnected one by one to measure in the connector, as shown in the text and images above.

Related page: