General:

In a gasoline engine, the fuel/air mixture must be ignited at the end of the compression stroke. This occurs when the spark plug creates a spark. A voltage between 20,000 and 30,000 volts is required to make the spark plug spark. A coil converts the battery voltage (around 12 to 14.8 volts) into this high voltage.

In older systems, there is often one coil bolted somewhere on the engine block, which is connected to the spark plugs via spark plug wires. Newer engines often have pen coils. Each spark plug then has its own coil. The number of coils on the engine can be easily recognized by the presence of spark plug wires. If spark plug wires run to each cylinder, the car has one fixed coil or a DIS coil. If there are no spark plug wires, then there is a separate coil on each spark plug. Often, a motor cover must be removed to see this.

Coil Ignition:

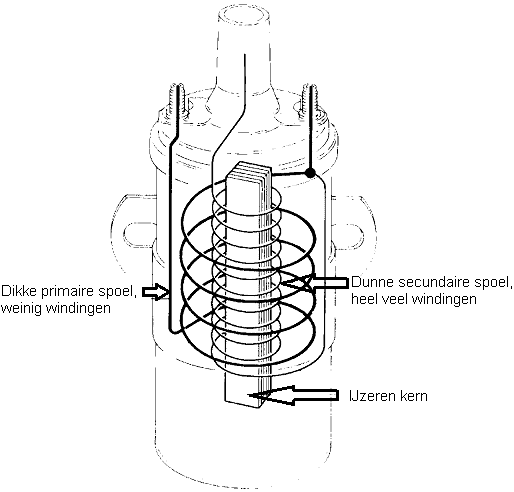

An ignition system uses a coil. Regardless of the type (conventional or computer-controlled), the principle remains the same. Inside the coil are two coils of copper wire around an iron core. The primary coil (on the ignition switch side) has few turns of thick wire. The secondary coil has many turns of thin wire. A voltage of 12 volts is applied to the primary coil. A current of 3 to 8 Amperes flows through this primary coil, thus creating a magnetic field. When this magnetic field collapses, a voltage of 250 to 400 volts is induced in the primary coil. Due to the difference in the number of turns, a voltage of up to sometimes 40,000 volts is induced in the secondary coil.

The primary coil of the coil has an ohmic and inductive resistance. The ohmic resistance can be measured with the multimeter or calculated from current or voltage measurements. The inductive resistance relates to the magnetic field developed in the primary coil and depends on the rate at which the current changes and the magnetic properties of the coil (the L-value). Each coil has a fixed L-value, which depends on the number of turns and the dimensions of the coil and the properties and dimensions of the core.

Conventional Distributor Ignition with Contact Points:

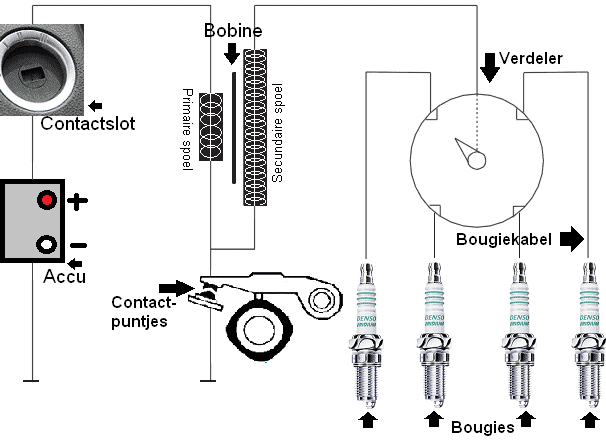

The conventional ignition system consists of a single coil that is switched on and off with contact points, coil wire, spark plug wires, and a mechanical distributor with ignition timing advance.

At rest, the contact points are closed. A current flows through the primary coil via the contact points to the ground. At that moment, a magnetic field is present in the primary coil. When the cam lifts the lever, the contact between the contact points is broken, and an induction voltage occurs. This induction voltage is amplified in the secondary coil and passed on to the distributor via the coil wire. The cam in the distributor points to one of the spark plug wire connections. The voltage is passed to the spark plug, which then produces a spark.

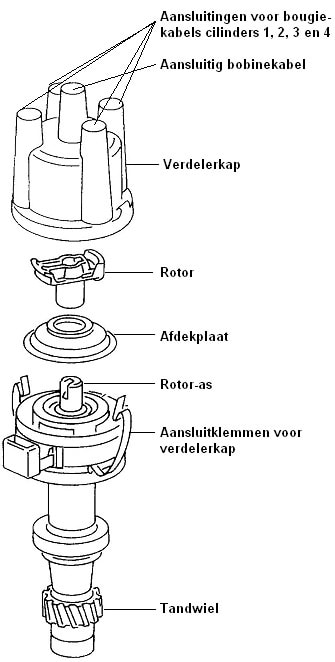

The coil delivers a high voltage through the connection of the coil wire to the rotor in the distributor. The rotor in the distributor rotates at half the crankshaft speed. This is made possible because there is, depending on the construction, a direct connection between the crankshaft and the distributor (as seen in the image), or because the rotor is directly driven by the camshaft. The camshaft already rotates at half speed relative to the crankshaft. The image shows an exploded view of the distributor.

The rotor is sensitive to maintenance. The contact points between the rotor and the distributor cap will corrode over time, which will reduce the quality of the spark plug spark. By occasionally sanding away the corrosion, or by replacing the worn parts, the quality of the spark remains optimal. By turning the distributor cap on the rotor, the ignition timing is adjusted.

Computer-Controlled Ignition:

Modern cars are equipped with computer-controlled ignition systems. The engine management system controls the coil. A pulse generator (crankshaft position sensor and sometimes a camshaft position sensor) provides a reference pulse that synchronizes with the crankshaft or camshaft. Often there is a missing tooth on a ring or pulley that serves as a reference point. The image shows the processed crankshaft pulley from the MegaSquirt project. The pulley has 36 teeth, one of which has been removed. That’s why it’s also called a 36-1 reference wheel. Every 10 degrees, a tooth passes by the sensor (360/36).

Each time the missing tooth passes the sensor, a signal is sent to the ECU.

This reference point is not the top dead center (TDC) as its name often suggests. In reality, this reference point is located between 90 and 120 degrees before the TDC. This means that when there is no ignition advance, the ignition pulse occurs 9 to 12 teeth after the reference point.

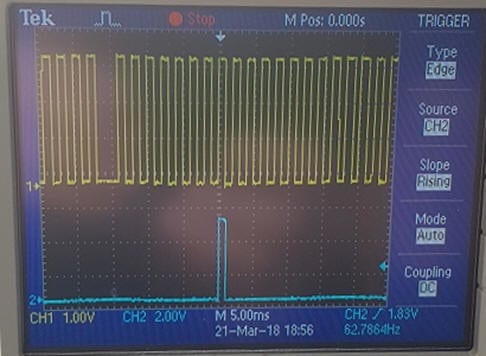

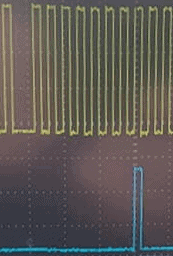

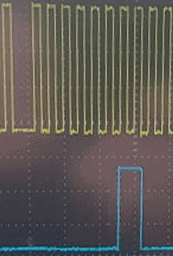

In the image, the crankshaft signal (yellow) is shown in relation to the coil’s control pulse (blue). In the crankshaft signal, the missing tooth is visible where the pulse is missing. In this engine, the missing tooth is located 90 degrees before TDC (which is 9 teeth of the pulse wheel).

Between the missing tooth (reference point, yellow) and the control pulse (blue), 8 teeth are visible; here, there is an advance of 10 degrees.

The advancing of the ignition is related to the combustion speed; the combustion requires time to reach its maximum combustion pressure. This maximum combustion pressure is optimal at a crankshaft position of 15 to 20 degrees after TDC. This must be optimal under all operating conditions. The following sections explain the impact of the ignition timing on combustion pressure, how ignition advance occurs, and how the dwell time can be read in the oscilloscope image.

Combustion Pressure and Ignition Timing:

The ignition system must ensure that the mixture in the cylinder space ignites at the right moment. When the piston has passed the TDC, the combustion pressure should be highest. Since there is a delay between igniting and burning of the mixture (when maximum combustion pressure is reached), the mixture must be ignited long before the TDC. In short: the spark plug must have sparked before the piston reaches the TDC.

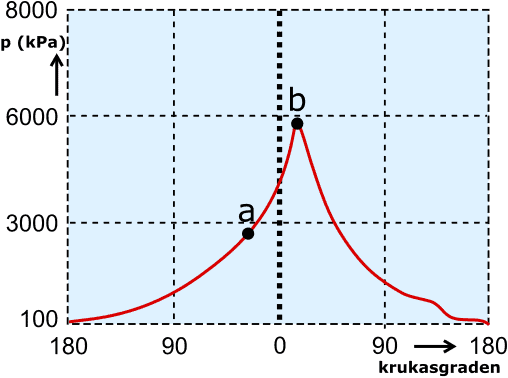

In the following diagram, we see the pressure curve (red line) in relation to the crankshaft degrees. At point a, the spark plug sparks. The piston moves further towards the TDC (0) and the combustion pressure rises. Approximately 10 to 15 degrees after the TDC (at point b), the maximum combustion pressure is reached.

- if point b moves too far to the left, the mixture ignites too early, and the piston is held back during upward movement;

- when point b moves to the right, the combustion occurs too late. The piston has already moved too far towards the BDC. The power stroke is no longer effective enough.

Ignition Advance:

To have the pressure peak occur at the correct crankshaft position, it is important to advance the ignition when the speed increases. Point b (the maximum combustion pressure) must not be moved. During the advancing and delay of the ignition timing, point a (ignition moment) is shifted to the left or right. The combustion time depends on the fill degree of the engine and the current mixture ratio. Therefore, the ignition advance is different for every engine. This is also why the crankshaft reference point is set a few degrees before the TDC: between the reference point and the TDC, there is time to calculate the ignition advance.

For a DIS coil (described further down the page), the crankshaft position sensor is sufficient to determine the ignition timing. The first pulse after the missing tooth is used to, for example, charge the secondary coil of cylinders 1 and 4. Then, the number of teeth is counted (in this case, 18) to generate the pulse for the secondary coil of cylinders 2 and 3. When the engine is equipped with COP coils, one reference point is not enough. In that case, a camshaft position sensor is needed to detect multiple reference points.

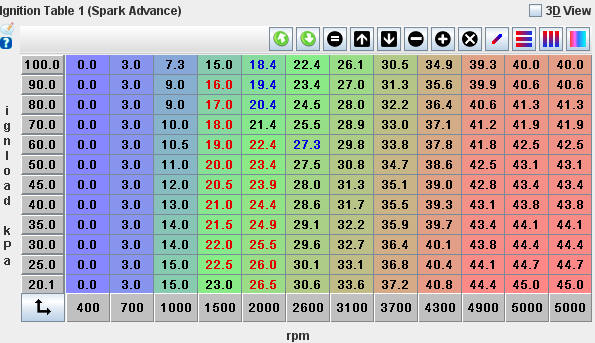

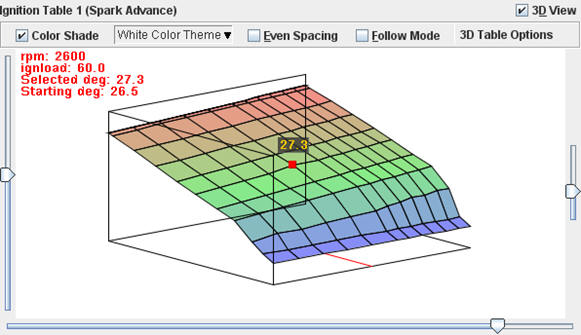

The two images below (ignition advance table and 3D view) show the settings of the ignition map in the MegaSquirt project. These are called lookup tables, reference, or core fields.

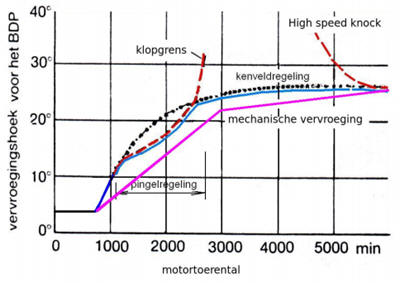

Ignition advance is determined based on the engine configuration. The graphs show the full-load ignition advance curves for (conventional) mechanical distributor ignition (pink line) and a computer-controlled system (blue line). The kink in the pink line is the point where the vacuum advance comes into play. Furthermore, the lines are completely straight; this is due to mechanical limitations. In a computer-controlled system, this can be regulated more precisely; therefore, the ignition curve runs as a curve. Between 1200 and 2600 rpm, the blue line is slightly pulled down; this is related to the part-load knocking area. Furthermore, it is visible that both the conventional and computer-controlled advance lines end at approximately 25 degrees. The advance must not go further up, as there is a risk of “high-speed knock,” or the knocking area at high speed.

The ignition map serves as a basis for ignition advance. From this point, the engine management system will try to advance the ignition as much as possible. Too much advance will lead to knocking; this is detected by knock sensors. When the knock sensors detect that the engine tends to knock, the engine management system will retard the ignition timing by a few degrees. Then, it will advance again until the knock sensors give a signal.

Dwell Time:

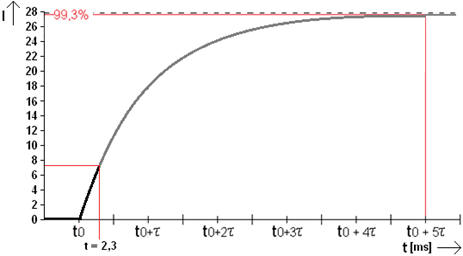

When the primary current is turned on, a magnetic field is built up. The current through the coil will not immediately reach its maximum value; this takes time. In the coil, there is resistance obtained from a counteracted inductive voltage. Additionally, the current will not rise further than 6 to 8 Amperes. In 2.3 milliseconds, enough energy is generated for the spark plug to produce a spark sufficient to ignite the air-fuel mixture. The point t=2.3 ms is the ignition timing. The current build-up from time t0 to t=2.3 ms is called the dwell time of the primary coil.

The current build-up in the primary coil stops at about 7.5 Amperes. The current must not rise further, as the primary coil may become too hot. When the car’s board voltage drops, more time is needed to charge the primary coil. The ignition timing does not change. Therefore, charging must start earlier. This is visible in the image, where the green line shows the coil’s switch-on phenomenon at a lower voltage. The charging process starts earlier (delta t) and ends at the same moment as the black line at 7.5 A.

The coil’s control changes; the width of the control pulse affects the dwelling time of the primary coil. The longer the pulse is, the longer the coil has time to charge.

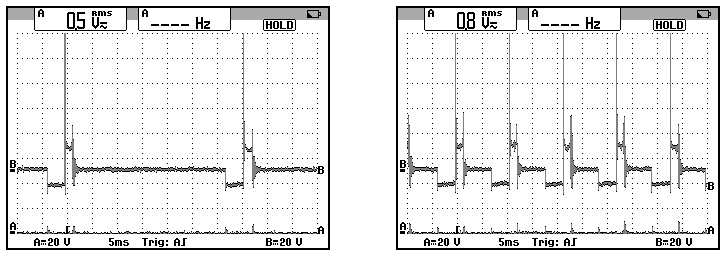

In both images, ignition occurs at the eighth tooth (80 degrees before TDC). The right image shows the longer dwell time.

DIS Ignition:

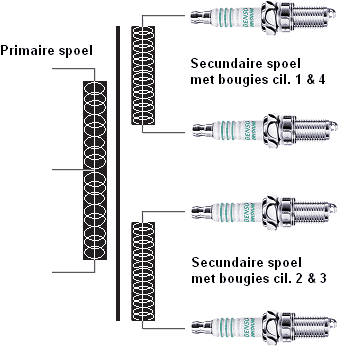

DIS stands for Distributorless Ignition System. As the name implies, it is an electronic distributorless ignition. The signal to ignite comes directly from the ECU, making it a computer-controlled ignition. In this ignition system, 2 coils are combined into 1 housing. Each coil provides the spark for 2 cylinders. One coil is mounted on cylinders 1 and 4, and the other coil is on cylinders 2 and 3.

Let’s use the DIS coil with connections for cylinders 2 and 3 as an example. There is no rotor present, which means they will both spark simultaneously. Cylinder 2 is at the end of the compression stroke, and the coil sparks to ignite the mixture. This means the coil also sparks on cylinder 3, which is starting the intake stroke. Since it does not yet have a combustible mixture, it does not matter. Later, when cylinder 3 is in the compression stroke, cylinder 2 will be in the intake stroke and receive the unnecessary spark. The waste spark in the cylinder where no combustion occurs does not cause the spark plug to age faster. The spark only requires a voltage of 1kV (1000V) instead of 30kV when burning a mixture.

The advantage of the DIS coil is that it requires virtually no maintenance. The coil is maintenance-free. The disadvantage of this coil is that moisture can sometimes penetrate between the cable and the connection shaft in the coil. Moisture causes corrosion on the contacts, which turn white or green. The spark voltage drops due to the large voltage loss caused by the corrosion. The engine may start to shake and vibrate slightly without an actual fault being registered in the ECU’s memory. In such a complaint, it is wise to disconnect the cables from the coil one by one (while the engine is off!!) and check that the contacts are nicely gold-colored and that there are no signs of corrosion in the cable and shaft. The corrosion is very aggressive and will slowly return after cleaning. The best solution is to replace the complete coil with the related cable.

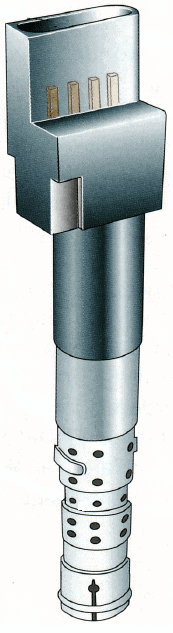

One Coil per Cylinder:

In this ignition system, coil-on-plug (COP) coils are directly mounted on the spark plug. Here, too, the engine control unit (ECU) regulates the ignition. Both the current strength and the ignition timing are calculated by the control unit. It functions like an older coil; this coil also has a primary and secondary coil. The primary coil is supplied with voltage via the connector at the top and internally interrupted via a transistor.

The disadvantage of these coils is that they are installed in the spark plug shaft and can become extremely hot. Although they are designed for this, they sometimes fail. This can be recognized when a car skips a cylinder causing the engine to shake. When this happens, the oxygen sensor will detect that a coil does not ignite the fuel, and fuel injection on that cylinder will be stopped. That cylinder is then completely out of operation. This prevents unburned fuel from entering the exhaust and damaging the catalyst. A faulty coil can often be identified by the engine running very irregularly (and the check engine light is on, although this light can have many causes).

More information and causes of cylinder misfire can be found on the cylinder misfire page.

If there is a suspected coil fault, the primary ignition pattern can be viewed with the oscilloscope, if the engine is in limp mode and the ignition and injection have been shut off while running.

Measuring Primary Ignition Pattern with the Oscilloscope:

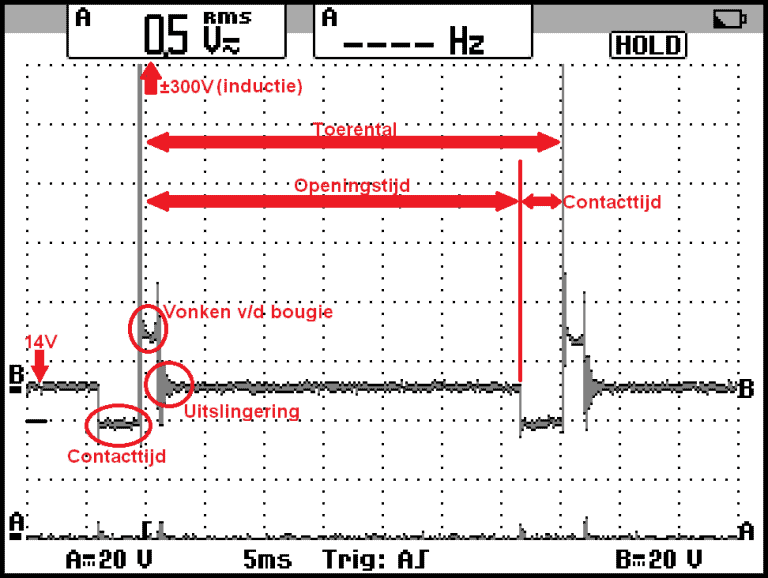

The coil generates the voltage so that a strong spark can develop at the bottom of the spark plug. The coil must generate a voltage of approximately 30,000 to 40,000 volts to make a spark jump in the spark plug. For this, an ionization voltage of 300 to 400 volts must be generated in the primary coil. In the voltage progression through the primary coil, we can see if this process goes well. The voltages of the primary and secondary coils are passed to each other, although the levels in the secondary coil are about 100 times higher. This makes it possible to see in the primary voltage pattern whether the coil is in order and if the spark plug fires properly. The oscilloscope image below was measured on the primary coil of a coil.

From left to right:

- 14 volts: at rest, we measure 14 volts at the positive and ground side of the coil in the coil;

- Contact time: the primary coil is grounded on one side. A differential voltage of 14 volts arises between the + and ground, allowing current to flow through the coil;

- 300 volts (induction): the ECU or ignition module’s final stage ends control, and an induction of approximately 300 volts occurs in the primary coil. This is called the ionization voltage. A voltage of 30,000 volts is generated in the secondary coil. This voltage is required to make the air between the spark plug electrodes conductive and to make a spark jump;

- Sparking of the spark plug: from the spark line we can see that the spark plug is sparking;

- Dampening: this is where the residual energy dissipates. This depends on the LCR value of the circuit (L-value of the coil and the capacitance of the capacitor).

The opening time in the oscilloscope image refers to the opening time of the contact points. In a computer-controlled ignition, this no longer applies. However, from the point where the ionization voltage of the second spark appears, we can determine the engine speed. The oscilloscope images below show the primary ignition patterns at low speed (left) and high speed (right).

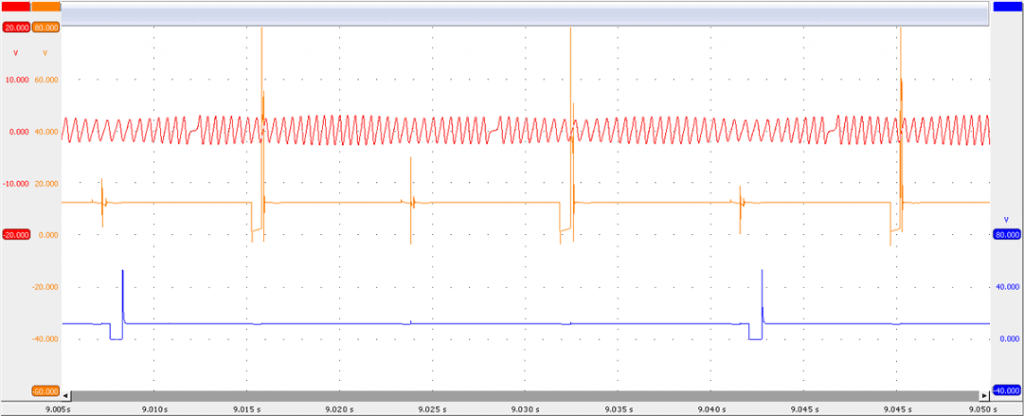

Using an oscilloscope, we can display the ignition pattern and injection pattern relative to the crankshaft signal. The reference wheel contains one reference point. After each crankshaft revolution, an ignition moment occurs. We know that the crankshaft must make two rotations for one complete work cycle. From this, we can recognize that we are dealing with a DIS coil. Hence, a “wasted spark” occurs. The injector patterns confirm this: injection takes place every other crankshaft revolution.

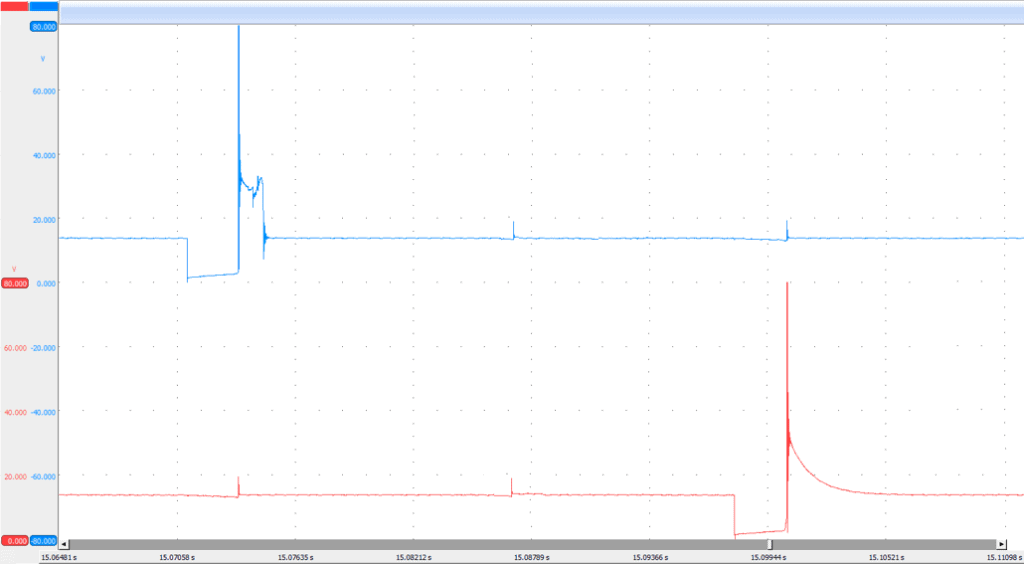

If it is suspected that a coil is defective, examining the secondary ignition pattern can determine whether a problem occurs in the secondary ignition. The resulting image shows the ignition pattern of cylinder 6 (blue) and cylinder 4 (red) in which a fault is present. The explanation follows under the image.

In the primary pattern of cylinder 4, the ionization voltage is visible, but then the energy dissipates. The pattern now has similarities with the characteristic voltage curve of a magnetic coil injector. What can we recognize in this pattern:

- Cylinder 6 (blue) is in order. This pattern is used as a reference;

- Cylinder 4: the ionization voltage is in order. Energy is generated in the primary coil. The primary coil is good;

- The control of the engine ECU or the external ignition module is in order;

- The secondary pattern is not visible;

- The primary and secondary coils do not exchange energy;

- The secondary coil is interrupted.

Experience shows that the secondary coil of a coil can fail due to heat. With an oscilloscope, we can trace this defect. Note: if the engine has gone into limp mode, control may be terminated. Therefore, perform the measurement immediately after or during the engine startup.