Hydrogen:

Hydrogen, referred to as hydrogen in English, can be used as an energy carrier to power vehicles. Energy carrier means that energy has already been stored in the hydrogen beforehand. This is in contrast to (fossil) energy sources such as oil, natural gas, and coal, where energy is obtained by processing these substances through combustion.

Hydrogen is thus very different from water injection, which is not used as an energy carrier in gasoline engines but purely for cooling the combustion chamber.

The goal with hydrogen is to achieve “zero emission”; a form of energy where no harmful gases are released during use. The transition from fossil fuels to electric propulsion, in combination with hydrogen and a fuel cell, is part of the energy transition. Powering vehicles with hydrogen can be done in two different ways:

- Using hydrogen as fuel for the Otto engine. The hydrogen replaces the gasoline fuel.

- Generating electrical energy with hydrogen in a fuel cell. Using this electrical energy, the electric motor will fully electrically drive the vehicle.

Both techniques are described on this page.

Hydrogen can be produced with sustainable energy or based on fossil fuels. The latter is something we try to avoid as much as possible because fossil fuels will become scarce in the future. Also, processing fossil fuels will produce CO2.

The columns below show the energy content of a battery, hydrogen, and gasoline. From this, we see that there is significant

Battery:

- Energy content: 220Wh/kg, 360 Wh/l

- Highly efficient

- Short-term storage

- Immediate energy release possible

- Transport is complex

Hydrogen (700 bar):

- Energy content: 125,000 kJ/kg, 34.72 kWh/kg

- 30% heat, 70% H2 (PEM fuel cell)

- Long-term storage possible

- Conversion required

- Transport-friendly

Gasoline:

- Energy value: 43,000 kJ/kg, 11.94 kWh/kg

- Efficiency up to 33%

- Long-term storage possible

- Conversion required (combustion)

- Transport-friendly

Hydrogen is ubiquitous in our surroundings, but never free. It is always bound. We will produce, isolate, and store it.

- 1 kg of pure hydrogen (H2) gas = 11,200 liters at atmospheric pressure

- H2 is smaller than any other molecule

- H2 is lighter than any other molecule

- H2 is always seeking connections

This page covers not only the production and application of hydrogen in passenger cars but also its storage and transportation (at the bottom of the page).

Hydrogen Production:

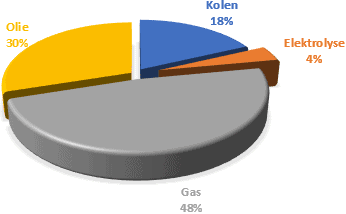

Hydrogen is a gas that, unlike natural gas, is not extracted from the ground. Hydrogen needs to be produced. This is done, among other methods, through electrolysis, a process in which water is converted into hydrogen and oxygen. This is the reverse of the reaction that occurs in a fuel cell. Additionally, hydrogen can be obtained through less environmentally friendly processes. The following data shows how hydrogen can be produced as of 2021.

- Coal: C + H20 -> CO2 + H2 + Nox + SO2 + … (temp: 1300C-1500C)

- Natural gas: CH4 + H2O -> CO2 + 3H2 (required temp: 700C-1100C)

- Oil: CxHyNzOaSb + …. -> cH2 + numerous by-products

- Electrolysis from water: 2H2O -> 2H2 + O2

Electrolysis from water is very clean and is the most environmentally friendly form of hydrogen production. Here, hydrogen and oxygen are released, unlike the processing of fossil fuels, where CO2 is released.

- Electrolysis of water; Electrolysis is a chemical reaction in which water molecules are split to create pure hydrogen and oxygen. Hydrogen can be produced anywhere there is water and electricity. A downside is that you need electricity to make hydrogen to then use it as electricity again. In this process, up to 50% is lost. The advantage is that energy is stored in hydrogen.

- Conversion of fossil fuels; Oil and gas contain hydrocarbon molecules composed of carbon and hydrogen. With a so-called fuel processor, hydrogen can be separated from carbon. The downside is that carbon is released as carbon dioxide into the air.

The hydrogen production obtained from fossil fuels is called gray hydrogen. During this process, NOx and CO2, among other things, are released into the atmosphere.

Since 2020, production increasingly occurs in “blue”: CO2 is captured.

The aim is to produce only green hydrogen by 2030: Green electricity and water are the sources for the most environmentally friendly produced hydrogen.

In the chemical world, hydrogen is denoted as H2, meaning a hydrogen molecule is composed of two hydrogen atoms. H2 is a gas that does not occur freely in nature. The H2 molecule is found in various substances, the most well-known of which is water (H2O). Hydrogen must be obtained by separating the hydrogen molecule from, for example, a water molecule.

Producing hydrogen through electrolysis is therefore the future.

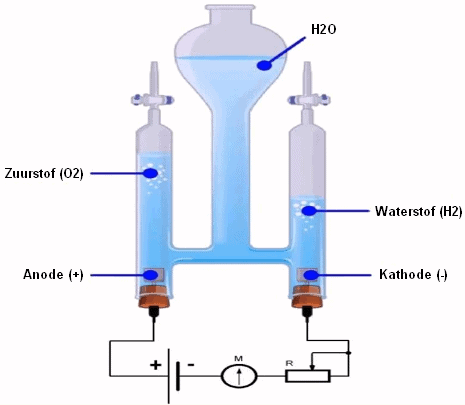

The following image shows a model that is often used in chemistry lessons.

- The positive and negative poles of a battery are immersed in water;

- On the anode side, you get oxygen;

- On the cathode side, you get hydrogen.

Hydrogen produced from fossil fuel, for example, Methane (CH4), is converted into H2 and CO2 via reforming in this case. The CO2 can be separated and stored underground, for example, in an empty natural gas field. Thus, the use of natural gas contributes little or not at all to CO2 emissions into the atmosphere. Hydrogen can also be made from biomass. If the CO2 released during this process is also separated and stored underground, it is even possible to achieve negative CO2 emissions; extracting CO2 from the atmosphere and securing this CO2 on Earth.

Hydrogen, unlike fossil fuels such as oil, natural gas, and coal, is not an energy source but an energy carrier. This means that the energy released during the use of hydrogen, for example, as fuel in a car, must first be input. For the production of hydrogen through electrolysis, electricity is needed. The sustainability of this hydrogen largely depends on the sustainability of the electricity used.

Hydrogen as Fuel for an Otto Engine:

An Otto engine is another name for a gasoline engine, as the gasoline engine was invented in 1876 by Nikolaus Otto. In this case, we call it an Otto engine because the gasoline is replaced by another fuel, namely hydrogen. In an engine where hydrogen is injected, there is no longer a gasoline fuel tank.

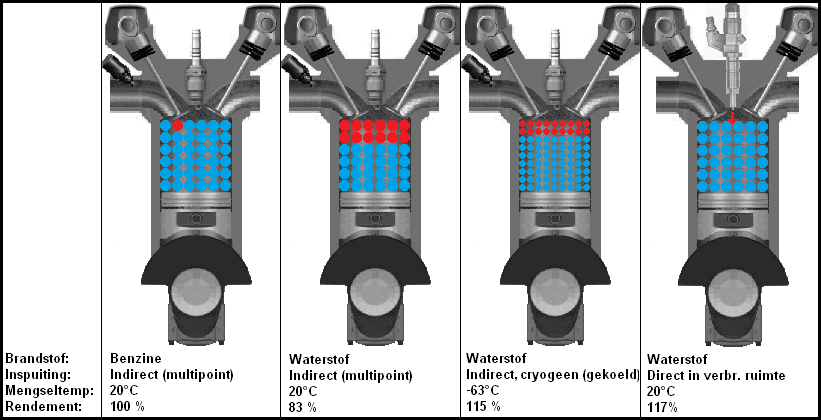

When hydrogen is burned, no CO2 gases are produced, unlike conventional Otto and diesel engines, but only water. When hydrogen is injected through direct injection, there will be a power increase of 15 to 17% compared to gasoline fuel. When hydrogen is injected at the intake valve (in indirect injection), the air causes rapid heating. The air is also displaced by the hydrogen. In both cases, less oxygen (O2) enters the combustion chamber. In the worst case, there is a power loss of up to 50%.

The air-to-hydrogen ratio is not as precise as, for example, an air-to-gasoline mixture. Therefore, the shape of the combustion chamber is not of great importance.

Hydrogen can be injected in two ways:

– Liquid: In liquid hydrogen supply, the combustion temperature will decrease relatively because of evaporation, resulting in less NOx.

– Gaseous: When hydrogen is stored in liquid form in the tank and enters the combustion chamber under ambient temperature, a vaporizer must be used to convert the hydrogen from liquid to gaseous state. In that case, the vaporizer is heated by the engine’s coolant. Possible measures to reduce NOx include the use of EGR, water injection, or a lower compression ratio.

The image below shows four situations with three different types of hydrogen injection. In the second image from the left, hydrogen gas is indirectly injected into the intake manifold. The gaseous hydrogen is heated by ambient temperature. Hydrogen also takes up space, allowing less oxygen to enter the cylinder. This is the situation where the most power loss occurs.

In the third image, liquid hydrogen is supplied. Cryogenic means the hydrogen is significantly cooled (a method to store large amounts of hydrogen in liquid form in a relatively small storage tank). Because the temperature of the hydrogen is lower and it is in a liquid state, better cylinder filling occurs. Due to the low temperature, almost as high efficiency as a direct (hydrogen) injection engine is achieved. The engine with direct injection is shown in the fourth image. The entire combustion chamber is filled with oxygen. When the intake valve is closed and the piston is compressing the air, a certain amount of hydrogen is injected through the injector. The spark plug is behind or beside the injector in this engine (not visible in the image).

The efficiency of an Otto engine is naturally not 100%, but this image compares the efficiency of hydrogen combustion with gasoline combustion.

Hydrogen has a high energy density per unit of mass (120MJ/kg), nearly three times higher than gasoline. The good ignitability of hydrogen allows the engine to run very lean, with a lambda value of 4 to 5. The downside of using a lean mixture is that the power output will be lower and the driving characteristics less optimal. To compensate for this, pressure charging (a turbo) is often used.

Due to a larger ignition area compared to gasoline fuel, the risk of detonation or a backfire is greater. It is therefore very important to have good control of the fuel supply and ignition. Under full load, the temperature in the combustion chamber can rise very high. Water injection is often needed to provide sufficient cooling and to prevent premature ignition (in the form of detonation or a backfire).

Fuel Cell:

In the previous section, it was explained how hydrogen can serve as fuel for the combustion engine. Another application of hydrogen is in the fuel cell. A vehicle equipped with a fuel cell does not have a combustion engine but one or more electric motors. The electrical energy to operate the electric motors is produced by the fuel cell. A fuel cell is an electrochemical device that converts chemical energy directly into electrical energy, without thermal or mechanical losses. The energy conversion in the fuel cell is thus very efficient. In general, the fuel cell operates on hydrogen, but a fuel such as methanol can also be used for this.

A fuel cell is essentially comparable to a battery, as both produce electricity through a chemical process. The difference is that the stored energy in the battery is released once. The energy runs out over time, requiring the battery to be recharged. A fuel cell provides continuous energy, as long as reactants are supplied to the electrochemical cell. Reactants are chemical substances that react with each other in a chemical reaction.

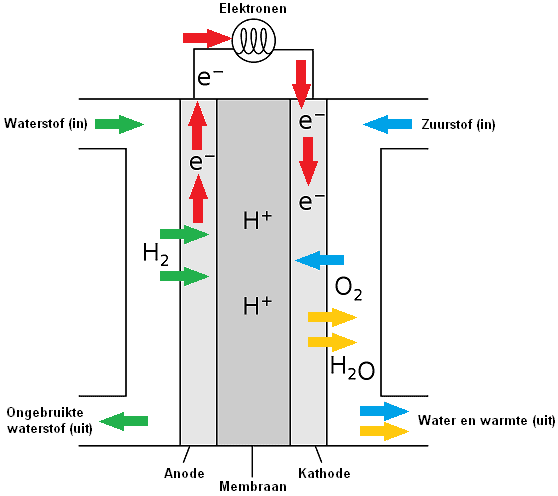

In a fuel cell, hydrogen and oxygen are converted into H+ and OH- ions (particles that are charged). The ions are separated into different chambers of the fuel cell by a membrane. The fuel cell contains two porous carbon electrodes on which a catalyst is applied; at the hydrogen (H) a negative electrode (anode) and at oxygen (O) a positive electrode (cathode).

H+ and OH- ions are driven towards each other via the electrodes (anode and cathode), after which the + and – ions react with each other. The cathode catalyzes the reaction where electrons and protons react with oxygen to form end product two, namely water. The H+ and OH- ions together form an H2O molecule. This molecule is not an ion because the electrical charge is neutral. The positive and negative charges cancel each other out to form a neutral particle.

Oxidation of hydrogen (H) occurs at the anode. Oxidation is a process where a molecule donates its electrons. The anode acts as a catalyst, causing the hydrogen to split into protons and electrons.

Reduction occurs at the cathode by adding oxygen (O). The electrons, released by the anode, travel to the cathode via an electric wire connecting the electrons externally.

By allowing the electron transfer to take place not directly but via an external route (the electric wire), this energy is largely released as electrical energy. The electrical circuit is closed by ions in a connecting electrolyte between the reducer and oxidizer.

The particle that captures electrons is called an oxidizer and is thus reduced. The reducer donates electrons and is oxidized. A reduction is the process where a particle captures electrons. Oxidation and reduction always occur together. The number of donated and captured electrons is always equal.

At the negative pole, the following reaction occurs:

At the positive pole, another reaction occurs, namely:

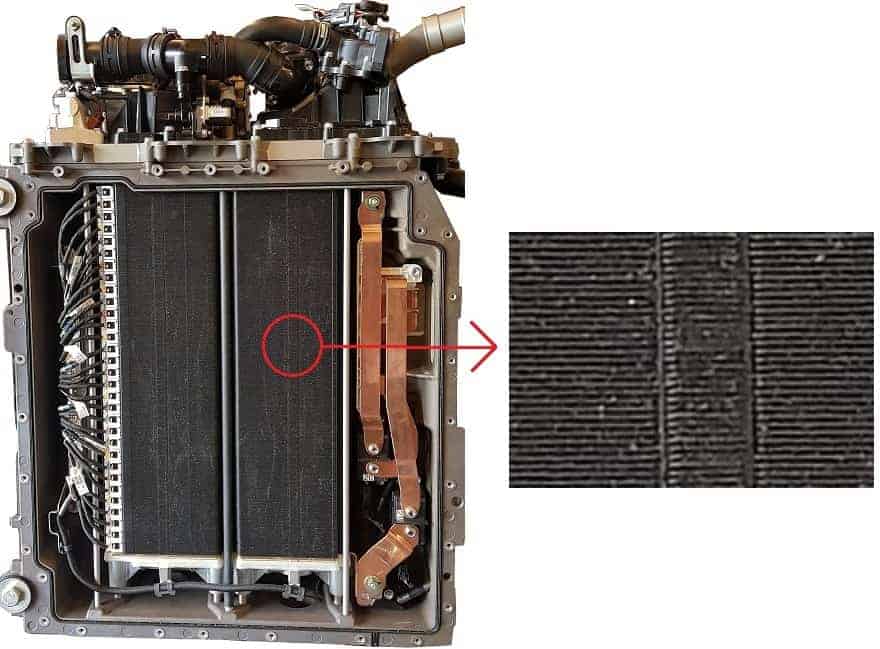

The image below shows the underside view of a fuel cell stack from a Toyota. This fuel cell stack is located under the hood of the car. Attached to this stack is the electric motor. The electric motor provides power to the transmission, which is connected to the drive shafts to transfer driving forces to the wheels.

On the top of the stack, various air ducts can be seen, including the air pump that pumps air to the fuel cells based on the power demand of the electric motor.

This fuel cell stack is equipped with 370 fuel cells. Each fuel cell provides 1 volt, so a total of 370 volts can be delivered to the electric motor. All the fuel cells are stacked beneath one another. The red circle shows an enlargement where the stacking of the fuel cells is clearly visible.

Storage Tank:

While hydrogen has a large energy density per unit of mass (120MJ/kg) and is nearly three times higher than gasoline, due to its lower specific gravity, the energy density per unit of volume is very low. For storage, this means hydrogen must be stored under pressure or in liquid form to apply a manageable storage tank by volume. For vehicle applications, there are two variants:

- Gaseous storage at 350 or 700 bar; at 350 bar, the tank volume for energy content is 10 times larger than gasoline.

- Liquid storage at a temperature of -253 degrees (cryogenic storage), with the tank volume for energy content 4 times larger than gasoline. In gaseous storage, hydrogen can be stored indefinitely without fuel loss or quality deterioration. In cryogenic storage, however, vapor formation occurs. Because the pressure in the tank increases due to warming, hydrogen will escape through the pressure relief valve; a loss of about two percent per day is acceptable. Alternative storage options are still under research.

The image below shows two storage tanks beneath the car. These are storage tanks where hydrogen is stored as a gas under a pressure of 700 bar. These storage tanks have an approximate wall thickness of 40 millimeters (4 centimeters), allowing them to withstand the high pressure.

Below is a repeat view of how the hydrogen tanks are mounted beneath the car. The plastic tube is the drainage of water that is formed during the conversion in the fuel cell.

Refueling Hydrogen:

At the time of writing this article, there are only two hydrogen refueling stations in the Netherlands. One of these stations is located in Rhoon (South Holland). The images show the nozzles used for refueling. The fill pressure is 350 bar in commercial vehicles and 700 bar in passenger vehicles.

The refueling connection on the car is located behind the usual fuel cap. The nozzle is connected to this refueling connection. After connecting the nozzle, it will lock. The car’s storage tank will be filled with gaseous hydrogen under a pressure of 700 bar.

Range and Costs of Hydrogen

As an example, we’ll take a Toyota Mirai (model year 2021) and examine the range and associated costs:

- Range of 650 km;

- Consumption: 0.84 kg / 100 km;

- Fuel price per km: 0.09 to 0.13 cents;

- Road tax €0,-

Compared to a vehicle with a diesel engine, a fuel cell car is not cheap. The costs of road tax play a significant role; however, the number of refueling stations in the Netherlands in 2021 is still scarce. Below is a comparison of costs per 100 km with current fuel prices:

BMW 320d (2012)

- Diesel: €1.30 per liter;

- Consumption: 5.8 l/100 km;

- Cost per 100 km: €7.54.

Toyota Mirai (2020):

- Hydrogen: €10 per kg;

- Consumption: 0.84 kg/100km;

- Cost per 100 km: €8.40

Related Pages:

- Electric Drive (overview);

- Energy Transition.