Introduction:

Automotive Ethernet, BroadR-Reach, and DoIP have been on the rise in modern vehicle communication for several years. Automotive Ethernet provides the physical and data link infrastructure for IP-based communication at high data speeds. BroadR-Reach formed the basis of today’s point-to-point Ethernet communication. DoIP is a diagnostic and programming transport that enables diagnostic communication via IP over automotive Ethernet.

In the first vehicles where Ethernet was implemented, it was mainly used for diagnostics and infotainment, where higher data rates were required than what was possible with the then-conventional CAN bus systems. As the number of ECUs, sensors, and software functions continues to grow, along with significant increases in data volumes from cameras, radar, central processing modules, infotainment, and connectivity, the role of Ethernet has expanded further.

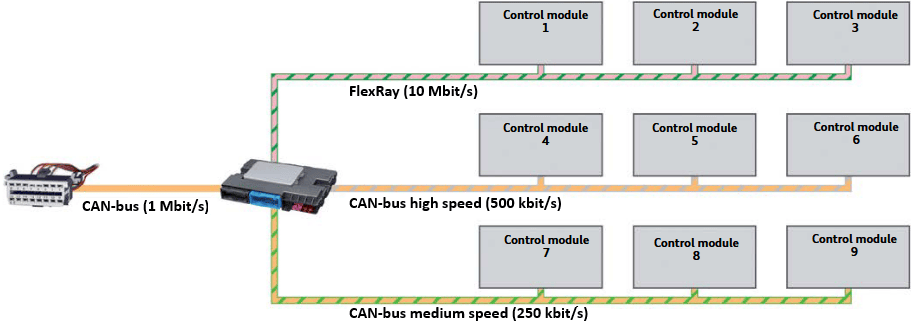

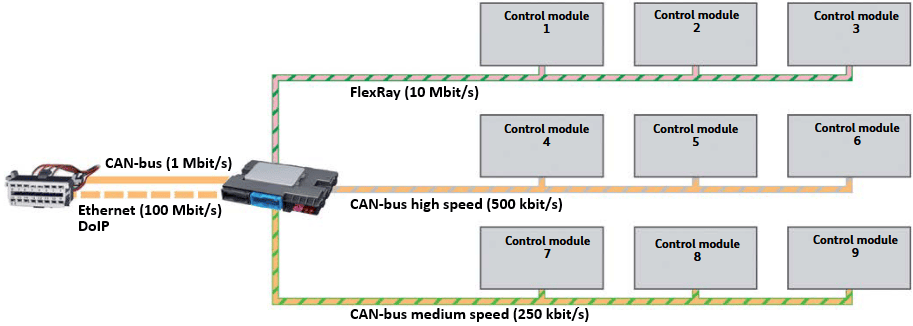

Networks such as CAN and LIN bus have been used in vehicles for a long time and remain suitable communication tools as long as the amount of information being sent is limited. However, for data-rich functions, these networks fall short in available bandwidth. For this reason, automotive Ethernet is being used more and more in modern vehicle communication. Alongside Ethernet, these vehicles still use networks such as CAN, LIN bus, and FlexRay.

Automotive Ethernet topology:

Automotive Ethernet uses the same protocol as the Ethernet we know from home, but adapted for vehicles. The most commonly used physical layers for automotive Ethernet are: 10, 100, and 1000 Mbit/s (Megabits per second). 1000 Mbit/s is equal to 1 Gbit/s (Gigabit per second). These are indicated in diagrams as 10BASE, 100BASE, and 1000BASE. The term “BASE” means baseband signaling (baseband transmission); the entire cable is used for a single Ethernet data connection. This section explains the topology, and the following sections describe specific properties for each speed.

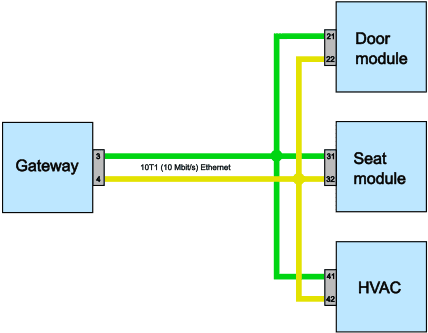

The topology of 10BASE-T1S, which has a bandwidth of 10 Megabits per second. ECUs in vehicles that are often connected to 10BASE-T1S are ECUs with low to medium data requirements that are located near sensors and actuators and do not require a continuous high data stream, such as door electronics, seat modules, or climate control.

Multiple ECUs are connected in parallel to a single twisted pair wire, similar to the topology of CAN bus and CAN-FD. The length of the bus and the maximum branches (stubs) are limited to avoid reflections and signal distortion. Therefore, specific guidelines apply for cable length, branch length, and termination, similar to other bus systems.

Because all ECUs share the same medium, only one ECU can transmit at a time. Bus access is not managed by arbitration as with CAN, but by Physical Layer Collision Avoidance. Each ECU is assigned a fixed time slot during which it is allowed to transmit. This results in predictable and collision-free communication on the shared bus, despite the use of Ethernet frames.

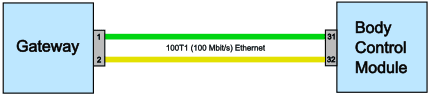

The topology of 100BASE and 1000BASE is characterized by a maximum of two ECUs communicating with each other via twisted pair Ethernet wires. This means: there is one ECU at each end of a wire pair. There are no nodes installed that connect other ECUs to this network, as seen in 10BASE Ethernet and CAN bus. In literature, you often see “module to module communication” or “ECU to ECU communication.” This refers to the topology described in this section.

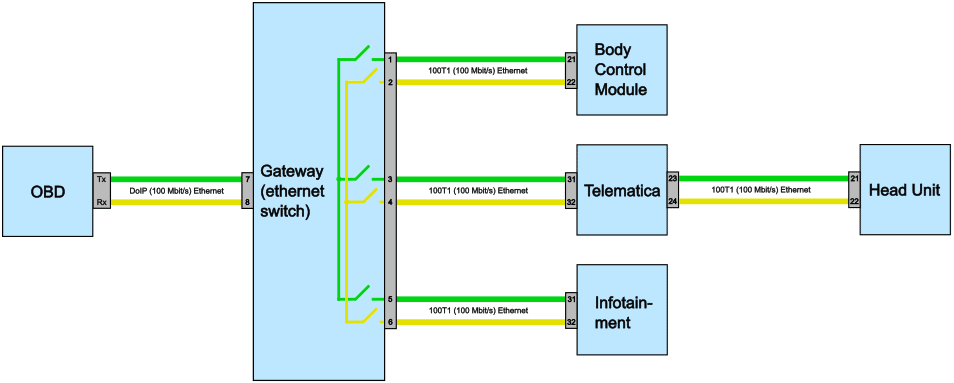

The ECUs of the 100BASE and 1000BASE, which are not directly connected to each other via Ethernet, can communicate with each other via an Ethernet switch. The switch can connect two (sub)networks as soon as communication between them is needed. Example: in the image below, the “Body Control Module” can communicate with the “Infotainment Module” via the Ethernet switch in the gateway.

Switches are often integrated into gateways or central processing modules. The physical switches are actually MOSFETs, which can be switched on and off by the electronics.

10BASE-T1S (10 Mbit/s)

This variant is used for Ethernet communication with sensors and actuators and is applied as an alternative or addition to CAN and CAN FD networks. The technology was developed for use in the lower speed domain of vehicles and uses a multidrop bus structure, in which multiple ECUs, sensors, and actuators are connected to one shared twisted pair. As a result, there is no need for a classic Ethernet switch per node, and the wiring harness can be made simpler and lighter.

Because multiple nodes share the same transmission medium, 10BASE-T1S operates in half-duplex mode. This means transmission and reception do not occur simultaneously, but alternate. To prevent collisions on the bus, Physical Layer Collision Avoidance is used. Each ECU is given a fixed time slot during which it is allowed to transmit. Only the ECU with the active time slot may place data on the bus. Other ECUs listen. This prevents collisions and eliminates the need for messages to be aborted or resent. This differs from CAN bus, where message priority is determined by arbitration.

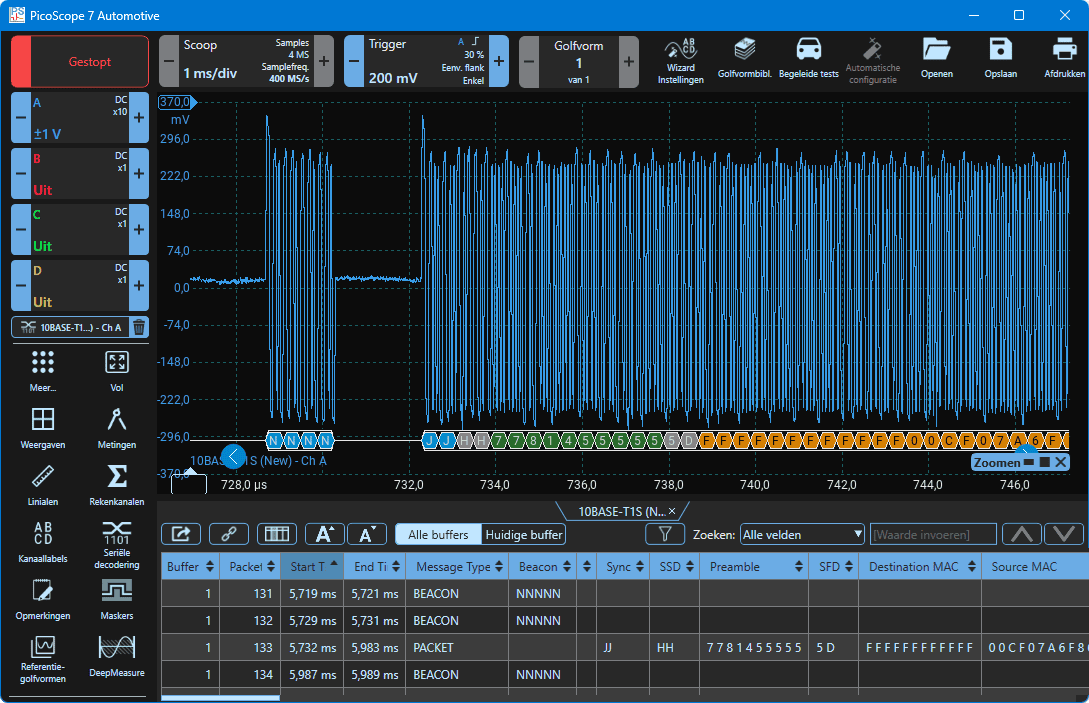

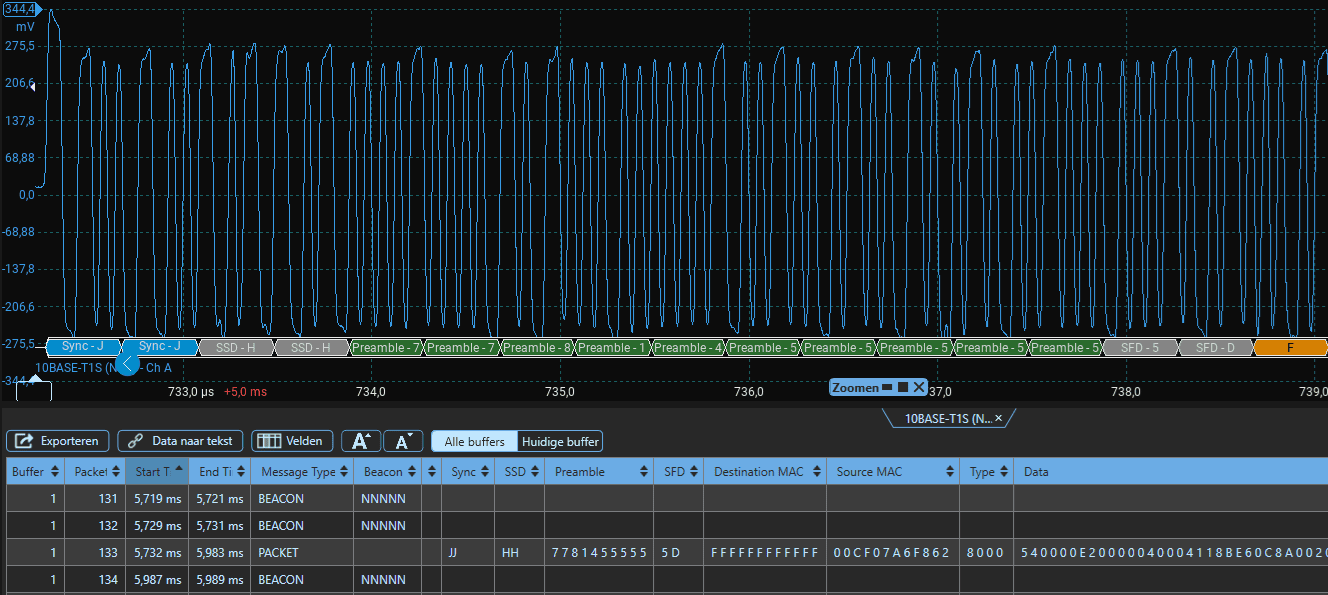

The oscilloscope screenshot below shows the signal behavior of 10BASE Ethernet, measured differentially on both Ethernet wires. The signal can be decoded using the Pico Automotive software. Characteristic for the 10BASE signal:

- The data rate is about 10 Mbit/s with a bit duration of approximately 100 ns per bit;

- At idle, the signal voltage is about 0 volts;

- The signal amplitude is approximately 300 mV positive and 300 mV negative (600 mV difference);

- Beacon frames: these are used for synchronization, similar to the “sync-field” with LIN bus. This is the first block labeled “N N N N” in the decoding.

- Packet frames: this is the message being transmitted. This is the sequence labeled from J to F in the coding. After the F, several more Fs are named, followed by the data and the end of the message.

The part from J to F is zoomed in below the oscilloscope image. The screenshots below zoom in further, also illustrating what J and F denote.

The oscilloscope screenshot below is a zoomed-in section of the image above (from J to F). By zooming in, the beginning of the package is partially visible. In the decoding we see the following parts:

- Preamble (7781455555): this is the synchronization between transmitter and receiver;

- SFD (Start Frame Delimiter, 5D): this marks the start of the frame;

- Destination MAC (FFFFFFFFFFFF): broadcast -> every node may receive this frame.

The first F of the Destination MAC is visible at the right side of the screenshot. The next screenshot shows the data from the last F of the Destination MAC onward.

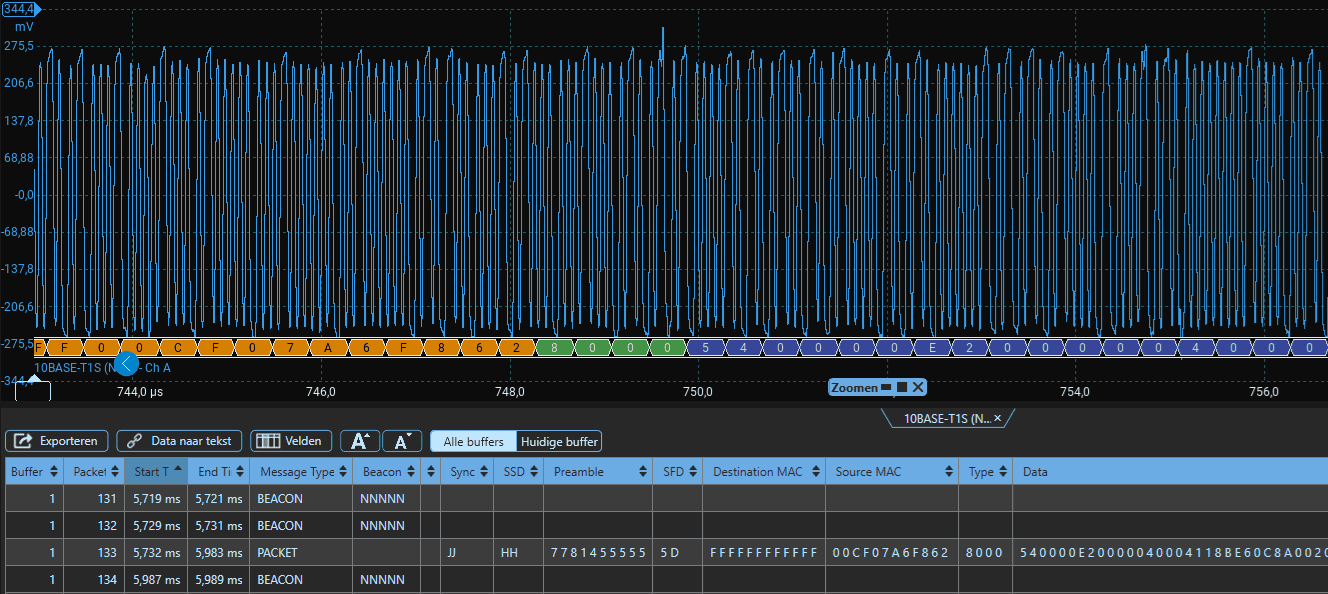

After the last F of the destination MAC, the message continues. This is shown in the screenshot below:

- Source MAC (00CF07A6F862): identifier of the ECU sending the message;

- Type (EthernetType, 8000): IPv4 (typical for DoIP);

- Data: starting with 540000E20000040004118BE60C8A0020.

The data is so long, it can’t possibly fit in a single screenshot.

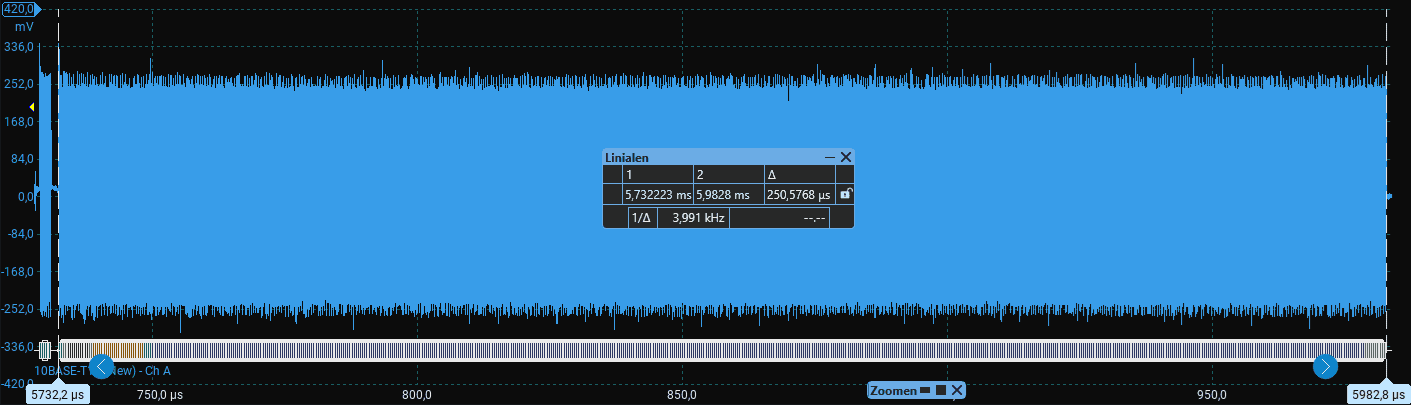

The screenshots above with explanations covered the first part of the Ethernet signal. Below is the complete signal. In the decoding, you can just see the orange and green sections on the left for the Preamble, Destination, and Source MAC. Then the blue/purple section of the decoding begins: this is where the data starts. In the screenshot above, the data starts with 540000E2000004000. The total amount of data is estimated to be about two hundred times larger.

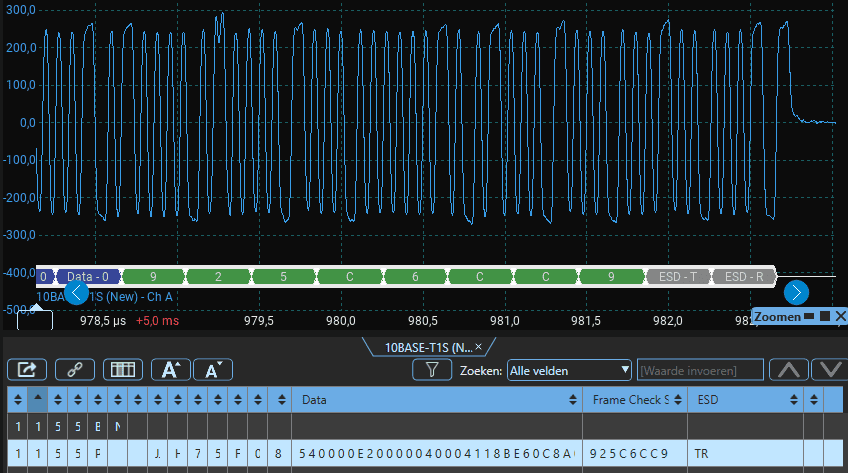

The screenshot below shows the end of the message, from the last data block to the ESD (End of Stream Delimiter), with the FCS (Frame Check Sequence) in between, which, like the CRC (cyclic redundancy check from CAN bus), sends a calculation for validation.

Finally regarding the 10BASE Ethernet signal: the entire message between the markers in the screenshot below lasts for around 250 microseconds (0.00025 seconds). The first 5% of the message has been explained in the three previous screenshots, illustrating that a huge amount of data is transmitted in a very short time. This is a key property of Ethernet: many messages can be sent in a short time due to large bandwidth. Although this shows that a lot of data can be transmitted in a short time, 10BASE is the slowest Ethernet we encounter in cars, but it is the variant that can be measured and decoded easily with a PicoScope Automotive oscilloscope. Unfortunately, the Automotive oscilloscope has too low a sampling rate to measure the faster systems properly.

100BASE-T1 (100 Mbit/s)

100BASE-T1 has a speed of 100 Megabits per second and uses point-to-point communication over an unshielded twisted pair. The connection always consists of exactly two ECUs that communicate exclusively with each other. There is no need to account for other ECUs sharing the transmission medium. The connection is full-duplex, which means communication can take place simultaneously in both directions. With 100BASE, there is no recessive state in which no data is sent: the link remains continuously active.

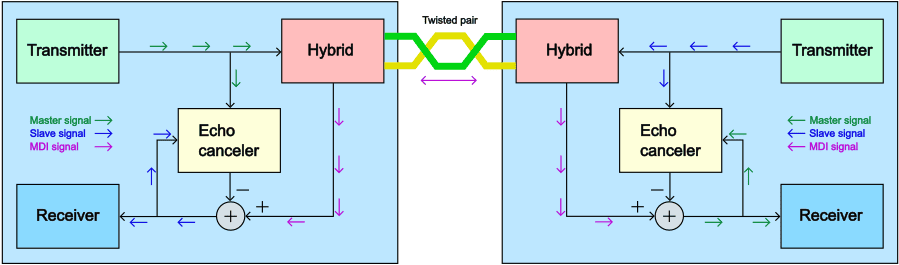

The image below shows how full-duplex communication over a single twisted wire pair is made technically possible. Both ECUs simultaneously transmit and receive via the same Ethernet wiring. The transmitter’s transmission signal is put onto the twisted pair via the hybrid, but part of that same signal leaks directly back to its own receiving chain. This leaked-back signal is called the echo. At the same time, the transmission signal from the other ECU comes in via the same wire pair. The signals on the Ethernet wires thus always contain a combination of the ECU’s own transmit signal, its echo, and the signal received from the other side.

The receiver measures this combined MDI signal and, without additional processing, cannot directly distinguish it. This is why the PHY contains an echo canceller. This echo canceller receives its own transmit signal from the transmitter and calculates the echo signal, which is then subtracted from the measured MDI signal. What remains is the transmitted signal from the other ECU, which can then be reliably decoded.

Because this process occurs continuously, both ECUs can continuously transmit and receive without waiting times or time slots.

These properties make 100BASE-T1 suitable for applications with fast, continuous data streams, such as camera data, infotainment, and communication between gateways and central modules. The difference with 10BASE is that with that variant, transmission and reception alternate on a shared medium, while with 100BASE both directions are active simultaneously via a point-to-point connection.

100BASE is used in systems such as cameras, telematics modules, gateways, and infotainment interfaces, where IP communication and higher bandwidth are needed, but where the ultra-high data rate of 1000BASE (1 Gbit/s) is not yet necessary.

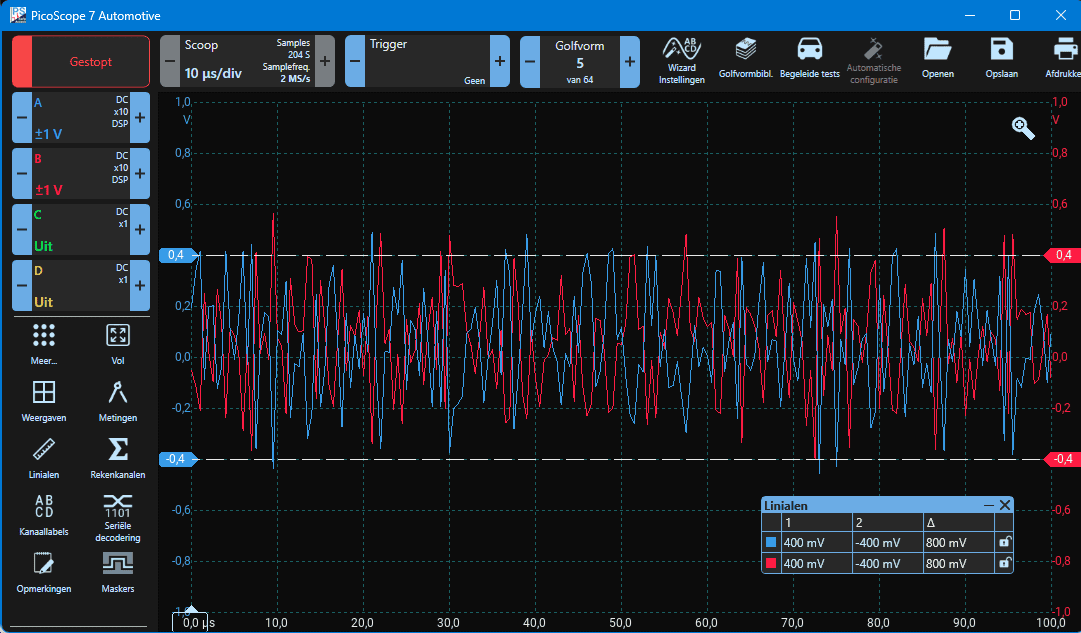

Below is a measurement displayed of the signal behavior of 100BASE Ethernet. Just like with CAN bus, the signals of channel A and B go in opposite directions: when the voltage of channel A goes high, the voltage of channel B goes low, and vice versa. The ECUs determine the voltage difference between the two signals.

The signal behavior of 100BASE is not pure. Clear data blocks are not visible as we can measure with 10BASE, and serial decoding is not possible. This is because the refresh rate of the Automotive oscilloscope is too low. To obtain a clean signal display and use the decode function, an oscilloscope in a higher price range should be used (about €5000 and up).

1000BASE-T1 (1000 Mbit/s = 1 Gbit/s)

Like 100BASE-T1, 1000BASE-T1 uses an unshielded twisted pair with differential signal transmission. The connection is also point-to-point and full-duplex, allowing simultaneous transmission and reception between two ECUs, with echo being filtered. This variant is used in systems where 100BASE-T1 does not provide enough bandwidth, such as high-resolution cameras for ADAS, radar and lidar systems, central processing units, video streams, and aggregated sensor data.

Due to the higher data rate and associated signal frequencies, 1000BASE-T1 places stricter requirements on wiring, connectors, and installation than 100BASE-T1. Deviations in twisting, increased contact resistance, or improper repairs affect signal quality more quickly and can result in unstable communication. For this reason, manufacturers often apply stricter specifications for wiring harness design, routing, and repairs for 1000BASE-T1.

BroadR-Reach:

BroadR-Reach was developed by Broadcom as an automotive Ethernet physical layer for 100 Mbit/s full-duplex communication over a single unshielded twisted pair. Later, this technology was also referred to as OPEN Alliance BroadR-Reach (OABR). BroadR-Reach was originally owned by Broadcom and not an open standard, so its use was initially mainly linked to Broadcom hardware. Ultimately, BroadR-Reach served as the technical foundation for the open 100BASE-T1 standard, specified in IEEE 802.3bw-2015.

BroadR-Reach forms the origin of the 100BASE-T1 connection and is no longer used as a distinct technology today. However, the term BroadR-Reach is still found in documentation and vehicle descriptions for older cars, where Ethernet connections are implemented that technically correspond to the current 100BASE-T1 standard.

DoIP (Diagnostics over Internet Protocol):

DoIP (pronounced as “doo-ip,” with IP pronounced as in internet protocol) stands for Diagnostics over Internet Protocol. DoIP is a diagnostic and programming protocol using IP communication via automotive Ethernet. In DoIP, diagnostic data is transmitted via Ethernet. As a result, data transfer is much faster than with CAN bus. If a car is equipped with DoIP at the OBD, many scan tools will ask whether you want to read out using CAN or DoIP.

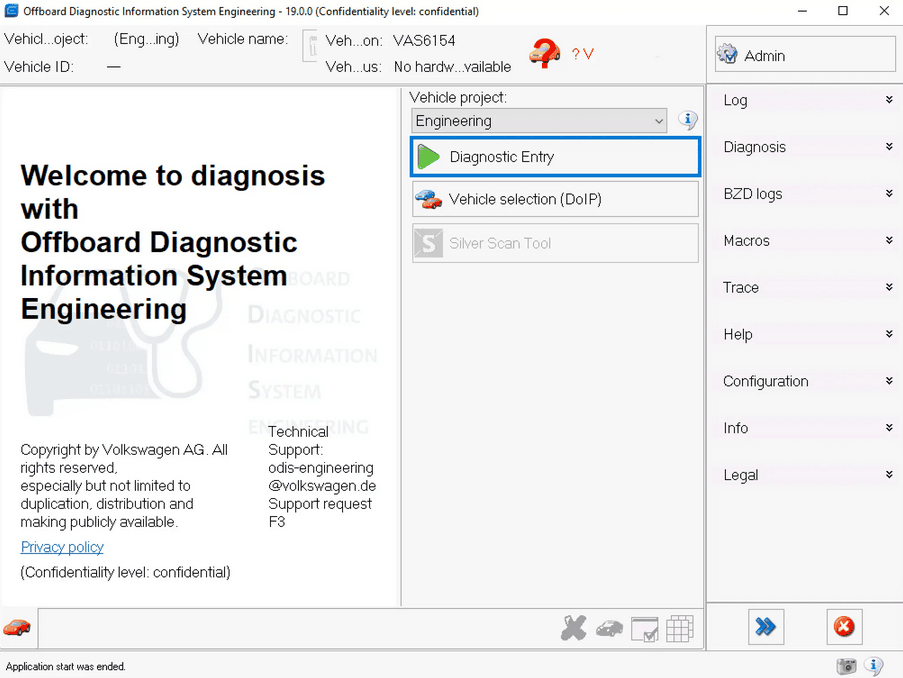

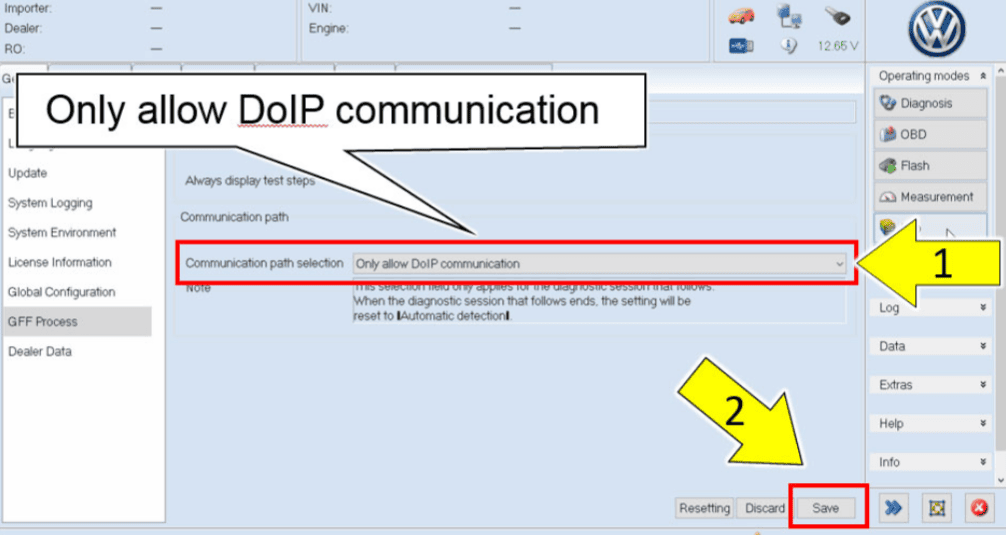

The main functional reason for using DoIP is the considerably higher data rate and communication speed compared to diagnostics over CAN. This is especially relevant when programming and flashing ECUs and when handling larger datasets. In practice, this means shorter programming times and faster loading times when reading vehicles with a lot of software and a large number of ECUs. When programming ECUs, it is sometimes necessary to manually switch from CAN to DoIP. The screenshots below show ODIS (VAG) with a selection option for DoIP before starting the scan, and the manual setting for flashing via DoIP.

In modern vehicles, DoIP communication usually goes through a central gateway. The diagnostic tool communicates via an Ethernet connection with this gateway, which uses internal switching functionality to forward traffic to the relevant ECUs. DoIP is not always directly active. Often a wake-up or activation condition is required before communication can take place. This is an important point for diagnostics: the absence of DoIP communication does not necessarily indicate a physical fault, but can also mean that the activation or session requirements are not met.

Wake-up line for DoIP:

The wake-up line is required to bring ECUs and the Ethernet network out of sleep mode before IP and DoIP communication is possible. Without wake-up, the Ethernet connection is often not active. Modern vehicles shut down ECUs and networks to save energy. This is called “sleep mode.” Automotive Ethernet ECUs, switches, and gateways are not active at the IP level in this state, often not even at the PHY level, and are therefore not visible for DoIP or diagnostics during sleep mode. That is why a separate wake-up mechanism is necessary.

The wake-up line is a simple electrical signal, usually a 12 volt or 5 volt signal depending on vehicle design, used to command an ECU or gateway to wake up. As soon as the wake-up is activated, the ECU exits sleep mode, the Ethernet PHY is switched on, and IP communication becomes active. Only then can DoIP communication take place. Without this activation, the ECU remains silent, even when the Ethernet cable is properly connected.

In practice, the wake-up can be activated by the ignition switch, opening a door, connecting a diagnostic tool, a separate wake-up pin in the OBD connector, or a CAN message that activates a gateway. With DoIP via the OBD connector, a specific pin is often used to wake up the central gateway or DoIP ECU.

DoIP always requires an active IP connection. So, in practice: no wake-up means no Ethernet link, no Ethernet link means no IP communication, and without IP, DoIP is not possible. This is an important point during troubleshooting.

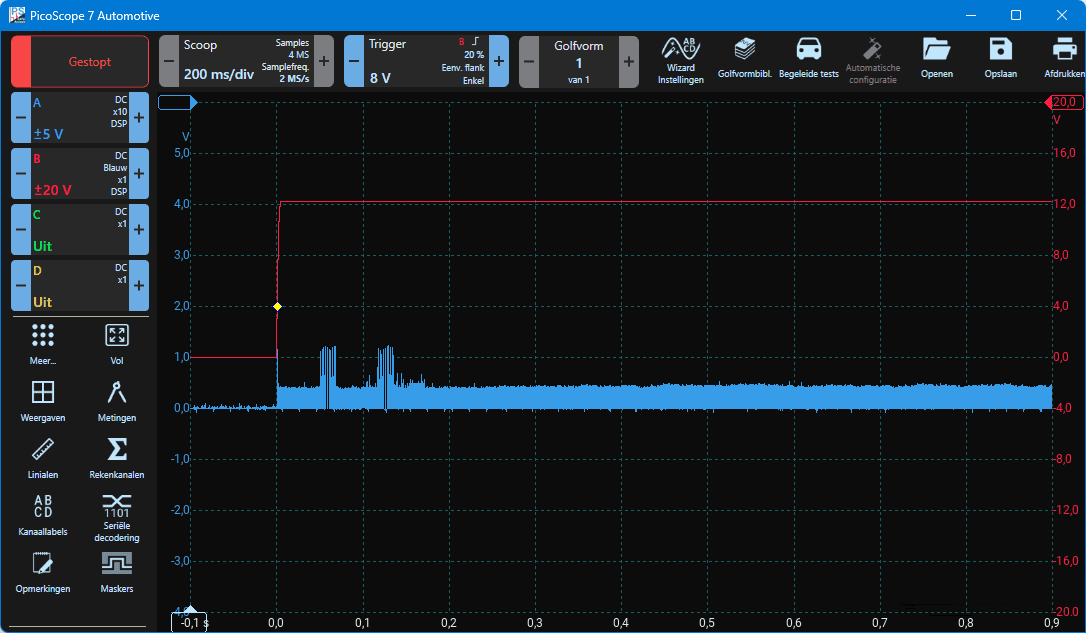

In the oscilloscope screenshot below, the wake-up line (channel B) can be seen rising from 0 to about 12 volts at t = 0 sec. At the moment the wake-up line is activated, communication on the Ethernet line begins. The result is visible on measurement channel A.

Power over Data Lines (PoDL)

With automotive Ethernet, in addition to data communication, power is increasingly transmitted over the same connection. This principle is referred to as Power over Data Lines. Here, power supply and data signals are combined over a single twisted pair, making additional power wires unnecessary.

This technology is comparable to POE (Power Over Ethernet) in home networking, where access points do not need a separate power wire aside from the UTP cable.

PoDL is especially relevant for sensors and peripheral devices such as cameras, radar and lidar units, and compact ECUs. By combining power and data over one connection, the wiring harness can be made lighter, thinner, and simpler. This provides advantages in weight, cost, and installation.

The power is added to the Ethernet connection via special injectors so that the data signals are not disrupted. On the receiving end, the power is separated from the data signal and used to power the connected module. The exact voltage and power levels are specified by standards and differ per application.

PoDL is an important point during diagnostics and repairs. A fault in an Ethernet connection can cause both data communication problems and a complete failure of a connected ECU due to missing power. As a result, it is not always immediately clear whether an error is caused by a data problem or a power problem. Measurements must also consider the presence of supply voltage on the data line.